Gabriel Winslow-Yost at the NYRB:

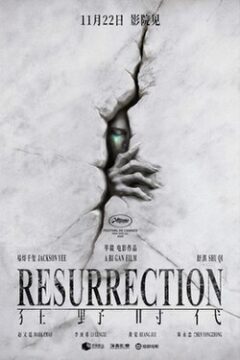

Films are rarely made in response to film critics, so it is unlikely that Bi Gan’s wildly ambitious new film was inspired Susan Sontag’s 1996 essay “The Decay of Cinema.” In any case, Bi was six years old, living in Kaili, China, when Sontag declared in The New York Times that “cinema’s 100 years seem to have the shape of a life cycle: an inevitable birth, the steady accumulation of glories and the onset in the last decade of an ignominious, irreversible decline.” “If cinema can be resurrected,” she concluded, “it will only be through the birth of a new kind of cine-love.” Yet Resurrection, as Bi’s film is called in English (its Chinese title is more like “Savage Age”—Bi has made a habit of giving his movies quite different titles in English and Chinese), seems conceived in exactly those terms. Its action spans that same century of movies, unified less by any continuity of plot than by the conviction that this era has come to an end. Cinema is dead. It may yet live again, but first: let us remember.

Films are rarely made in response to film critics, so it is unlikely that Bi Gan’s wildly ambitious new film was inspired Susan Sontag’s 1996 essay “The Decay of Cinema.” In any case, Bi was six years old, living in Kaili, China, when Sontag declared in The New York Times that “cinema’s 100 years seem to have the shape of a life cycle: an inevitable birth, the steady accumulation of glories and the onset in the last decade of an ignominious, irreversible decline.” “If cinema can be resurrected,” she concluded, “it will only be through the birth of a new kind of cine-love.” Yet Resurrection, as Bi’s film is called in English (its Chinese title is more like “Savage Age”—Bi has made a habit of giving his movies quite different titles in English and Chinese), seems conceived in exactly those terms. Its action spans that same century of movies, unified less by any continuity of plot than by the conviction that this era has come to an end. Cinema is dead. It may yet live again, but first: let us remember.

What little overarching story Resurrection has comes on title cards in the opening moments: in the future, we are told, humanity has stopped dreaming in order to prolong our lifespans. The few who can still dream—called “Deliriants” or, in an earlier translation, “Fantasmers”—are outlaws, hunted down and subdued lest they threaten the longevity of everyone else.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In this circumstance, there is not so much a vacuum as a cloud of uncertainty. Everything is up in the air. Expectations, assumptions and intentions are scrambled. Fearing lost advantage in the face of these unknowns, worst-case scenarios drive the build-out of capabilities. Acting in the breach is a wild guess, the possible outcomes of which cannot be assuredly weighed.

In this circumstance, there is not so much a vacuum as a cloud of uncertainty. Everything is up in the air. Expectations, assumptions and intentions are scrambled. Fearing lost advantage in the face of these unknowns, worst-case scenarios drive the build-out of capabilities. Acting in the breach is a wild guess, the possible outcomes of which cannot be assuredly weighed. Baghdad was cloaked in its familiar shroud of darkness when, in early October, I walked the al-Shuhada Bridge across the Tigris—more a ritual for me than a pastime. Long before Walter Benjamin described the Seine as “the vast and ever-watchful mirror of Paris,” the Andalusian traveler Ibn Jubayr saw the Tigris as “a mirror shining between two frames, or like a string of pearls between two breasts.” That image of splendor has long since dissipated. On the bridge that night, I passed by an old woman in her abaya sat begging on the curb; plastic waste lined the shallow waters below.

Baghdad was cloaked in its familiar shroud of darkness when, in early October, I walked the al-Shuhada Bridge across the Tigris—more a ritual for me than a pastime. Long before Walter Benjamin described the Seine as “the vast and ever-watchful mirror of Paris,” the Andalusian traveler Ibn Jubayr saw the Tigris as “a mirror shining between two frames, or like a string of pearls between two breasts.” That image of splendor has long since dissipated. On the bridge that night, I passed by an old woman in her abaya sat begging on the curb; plastic waste lined the shallow waters below. “L

“L Where are we exactly, in this deathless debate about the crisis of masculinity? We stand splattered in discourse, ears ringing from the unceasing alarm over men and their prospects — their lack of education and lack of friends, their porn and gambling, their suicide rates. This while tech elites, sporting their bulgy new bodies, call for an infusion of “masculine energy,” and a hideous new sport is born: “sperm racing.” Is it any wonder that a stance has emerged of principled contempt? The so-called crisis, according to its critics, is actually a crisis of accountability, a refusal on the part of men to regulate themselves emotionally and behave like adults. In this view, men aren’t in crisis, America is in crisis, and to suggest otherwise is to engage in a kind of “

Where are we exactly, in this deathless debate about the crisis of masculinity? We stand splattered in discourse, ears ringing from the unceasing alarm over men and their prospects — their lack of education and lack of friends, their porn and gambling, their suicide rates. This while tech elites, sporting their bulgy new bodies, call for an infusion of “masculine energy,” and a hideous new sport is born: “sperm racing.” Is it any wonder that a stance has emerged of principled contempt? The so-called crisis, according to its critics, is actually a crisis of accountability, a refusal on the part of men to regulate themselves emotionally and behave like adults. In this view, men aren’t in crisis, America is in crisis, and to suggest otherwise is to engage in a kind of “ A

A  The emotional experience of direct and renewed acquaintance with the realities of selective pressure, such as the sudden introduction of sexual jealousy into a seemingly safe relationship, has had for me an almost mystical character, as though what’s reawakened is the prehistory of my whole species, which unwinds from its reptilian recesses, ornamented with the bizarre, gemlike contingencies of thousands of howling animal triumphs and the wailing ghosts of unmutated failures, splitting my consciousness as though from underneath, a whole ocean bursting forth from the sudden shift of tectonic plates; but this alarming thing that emerges, this dark uncoiling dragon capable of incomprehensible violence, seems also dimly recognizable as simply, in some sense, my own self.

The emotional experience of direct and renewed acquaintance with the realities of selective pressure, such as the sudden introduction of sexual jealousy into a seemingly safe relationship, has had for me an almost mystical character, as though what’s reawakened is the prehistory of my whole species, which unwinds from its reptilian recesses, ornamented with the bizarre, gemlike contingencies of thousands of howling animal triumphs and the wailing ghosts of unmutated failures, splitting my consciousness as though from underneath, a whole ocean bursting forth from the sudden shift of tectonic plates; but this alarming thing that emerges, this dark uncoiling dragon capable of incomprehensible violence, seems also dimly recognizable as simply, in some sense, my own self. Let’s talk about a very 21st century scene. There’s an incident somewhere in the United States. The incident slots itself in neatly along the lines of preexisting ideological divisions. As the incident is unfolding, witnesses pull out their cell phone cameras to record it and those images are soon plastered across the web. Everybody sees essentially the same scene and everybody draws drastically different conclusions, depending on what their prior political convictions happen to be. And the result is a society split almost perfectly in two—disagreeing not only about underlying principles but even about which camera angles of an event, and which speed of playback, and which audio track, it prefers to focus on.

Let’s talk about a very 21st century scene. There’s an incident somewhere in the United States. The incident slots itself in neatly along the lines of preexisting ideological divisions. As the incident is unfolding, witnesses pull out their cell phone cameras to record it and those images are soon plastered across the web. Everybody sees essentially the same scene and everybody draws drastically different conclusions, depending on what their prior political convictions happen to be. And the result is a society split almost perfectly in two—disagreeing not only about underlying principles but even about which camera angles of an event, and which speed of playback, and which audio track, it prefers to focus on. When my daughter

When my daughter