Cassandra Willyard in Nature:

“This whole process, it’s just inefficient,” says Saar Gill, a haematologist and oncologist also at the Perelman School of Medicine. “If I’ve got a patient with cancer, I can prescribe chemotherapy and they’ll get it tomorrow.” With commercial CAR T, however, people have to wait weeks for treatment. That delay, along with the high cost of the therapy, plus the need for chemotherapy before people receive the CAR T cells, means many people who could benefit from CAR T never receive it. “We all want to get to a situation where CAR T cells are more like a drug,” says Gill.

“This whole process, it’s just inefficient,” says Saar Gill, a haematologist and oncologist also at the Perelman School of Medicine. “If I’ve got a patient with cancer, I can prescribe chemotherapy and they’ll get it tomorrow.” With commercial CAR T, however, people have to wait weeks for treatment. That delay, along with the high cost of the therapy, plus the need for chemotherapy before people receive the CAR T cells, means many people who could benefit from CAR T never receive it. “We all want to get to a situation where CAR T cells are more like a drug,” says Gill.

Some biotechnology companies have an answer: alter T cells inside the body instead. Treatments that deliver a gene for the CAR protein to cells in the blood could be mass produced and available on demand — theoretically, at a much lower price than current CAR-T therapies. A single dose of commercial CAR-T therapy costs around $500,000. A vial of in vivo treatment might cost an order of magnitude less.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

When Edward Said’s book,

When Edward Said’s book,  Richard Garwin, who died on May 13, 2025, at the age of 97, was sometimes called “

Richard Garwin, who died on May 13, 2025, at the age of 97, was sometimes called “ Israel’s former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert says he now believes his country’s relentless assault on the Palestinian people amounts to “war crimes” and must be stopped.

Israel’s former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert says he now believes his country’s relentless assault on the Palestinian people amounts to “war crimes” and must be stopped. In November, when the “Succession” creator Jesse Armstrong got the idea for his caustic new movie, “Mountainhead,” he knew he wanted to do it fast. He wrote the script, about grandiose, nihilistic tech oligarchs holed up in a mountain mansion in Utah, in January and February, as a very similar set of oligarchs was coalescing behind Donald Trump’s inauguration. Then he shot the film, his first, over five weeks this spring. It premiers on Saturday on HBO — an astonishingly compressed timeline. With events cascading so quickly that last year often feels like another era, Armstrong wanted to create what he called, when I spoke to him last week, “a feeling of nowness.”

In November, when the “Succession” creator Jesse Armstrong got the idea for his caustic new movie, “Mountainhead,” he knew he wanted to do it fast. He wrote the script, about grandiose, nihilistic tech oligarchs holed up in a mountain mansion in Utah, in January and February, as a very similar set of oligarchs was coalescing behind Donald Trump’s inauguration. Then he shot the film, his first, over five weeks this spring. It premiers on Saturday on HBO — an astonishingly compressed timeline. With events cascading so quickly that last year often feels like another era, Armstrong wanted to create what he called, when I spoke to him last week, “a feeling of nowness.” The artist

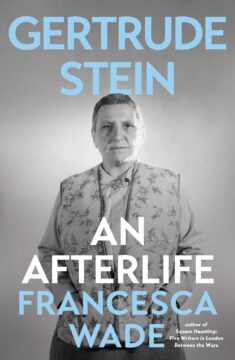

The artist  It’s not often that a biography really gets going after the author has reached the subject’s death. Gertrude Stein herself predicted that she would only be understood in the future: ‘For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause almost everybody accepts.’ She wasn’t entirely right, but Francesca Wade’s new ‘afterlife’ of Stein takes the sentiment seriously. The revolutions in language that preoccupied Stein in life were slowly appreciated after her death in 1946. Despite having an unpromising cast of scholars, librarians, publishers and fans, Wade turns the posthumous half of the Stein story into a narrative of suppression, revelation and hopes fulfilled. It helps that there is romance at the heart of it, and a secret notebook.

It’s not often that a biography really gets going after the author has reached the subject’s death. Gertrude Stein herself predicted that she would only be understood in the future: ‘For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause almost everybody accepts.’ She wasn’t entirely right, but Francesca Wade’s new ‘afterlife’ of Stein takes the sentiment seriously. The revolutions in language that preoccupied Stein in life were slowly appreciated after her death in 1946. Despite having an unpromising cast of scholars, librarians, publishers and fans, Wade turns the posthumous half of the Stein story into a narrative of suppression, revelation and hopes fulfilled. It helps that there is romance at the heart of it, and a secret notebook. Democratic National Committee (

Democratic National Committee ( At Friday afternoon’s

At Friday afternoon’s I

I