John Jeremiah Sullivan at Bookforum:

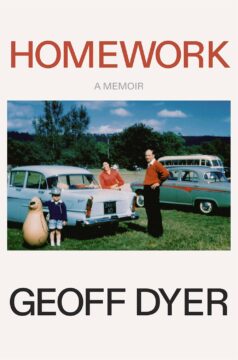

I WAS TRYING TO FIGURE OUT what struck me as odd, at first, about Geoff Dyer’s new memoir, Homework, when it dawned on me: it isn’t odd. The book, that is. Formally and in terms of genre, a Dyer book almost always represents a novel (so to speak) hybrid. His scholarly projects have a way of turning into memoirs and novels. Out of Sheer Rage began as an attempt to produce a study of D. H. Lawrence but became a book about his own inability to do so (even as it remained, in the words of The Guardian, a “very strange, sort-of study of D. H. Lawrence”). But Beautiful was conceived as a work of nonfiction jazz appreciation but became, in Dyer’s own description, “as much imaginative criticism as fiction.” His works of ostensibly pure fiction, meanwhile, have tended toward the auto-fictional, to such a degree that a reader could easily forget, at least for spans of pages, that they aren’t memoir. Take, for instance, the indelibly titled Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, concerning the adventures of “Junket Jeff,” a Dyer-like avatar who moves through the world of freelance-writer assignments and celebrity art profiles (the auto-fiction gets meta-meta when you encounter a distorted-mirror story involving a character named: Geoff). Dyer has written two essayistic travelogues: Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It and White Sands, each of which involves, again in his own unapologetic words, “a mixture of fiction and nonfiction.” There are also two books about movies, each having to do with an individual picture—Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room (on Tarkovsky’s metaphysical masterpiece Stalker) and Broadsword Calling Danny Boy (on the World War II action flick Where Eagles Dare)—both of which are so essayistic and at the same time hyper-focused, consisting entirely of Dyer’s digressive and ultra-personal responses to those films’ every scene, that they resemble neither “cinema studies” nor general-interest film crit. One could go on. James Wood put it well, writing about Dyer in The New Yorker, when he described the books as “so different from one another, so peculiar to their author, and so inimitable that each founded its own, immediately self-dissolving genre.”

I WAS TRYING TO FIGURE OUT what struck me as odd, at first, about Geoff Dyer’s new memoir, Homework, when it dawned on me: it isn’t odd. The book, that is. Formally and in terms of genre, a Dyer book almost always represents a novel (so to speak) hybrid. His scholarly projects have a way of turning into memoirs and novels. Out of Sheer Rage began as an attempt to produce a study of D. H. Lawrence but became a book about his own inability to do so (even as it remained, in the words of The Guardian, a “very strange, sort-of study of D. H. Lawrence”). But Beautiful was conceived as a work of nonfiction jazz appreciation but became, in Dyer’s own description, “as much imaginative criticism as fiction.” His works of ostensibly pure fiction, meanwhile, have tended toward the auto-fictional, to such a degree that a reader could easily forget, at least for spans of pages, that they aren’t memoir. Take, for instance, the indelibly titled Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, concerning the adventures of “Junket Jeff,” a Dyer-like avatar who moves through the world of freelance-writer assignments and celebrity art profiles (the auto-fiction gets meta-meta when you encounter a distorted-mirror story involving a character named: Geoff). Dyer has written two essayistic travelogues: Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It and White Sands, each of which involves, again in his own unapologetic words, “a mixture of fiction and nonfiction.” There are also two books about movies, each having to do with an individual picture—Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room (on Tarkovsky’s metaphysical masterpiece Stalker) and Broadsword Calling Danny Boy (on the World War II action flick Where Eagles Dare)—both of which are so essayistic and at the same time hyper-focused, consisting entirely of Dyer’s digressive and ultra-personal responses to those films’ every scene, that they resemble neither “cinema studies” nor general-interest film crit. One could go on. James Wood put it well, writing about Dyer in The New Yorker, when he described the books as “so different from one another, so peculiar to their author, and so inimitable that each founded its own, immediately self-dissolving genre.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Allison Rosen

Allison Rosen Last year,

Last year, It was an anxious summer. The American elections loomed, the sitting president had just been unmasked as an egomaniacal member of the walking undead, and here on the continent, across the Atlantic, Europe was about to elect the most right-wing parliament in the history of the European Union. The streets were plastered with campaign posters. In Germany, high over the boulevards, a well-known comedian gripped an enormous toothbrush and flashed her pearly whites. “Wählen ist wie Zähneputzen. Machst du’s nicht, wird’s braun!” read the accompanying text, or, “Voting is like brushing your teeth: don’t do it, and things’ll go brown.” The joke is that the Nazis wore brownshirts. To “go brown” is to go Nazi. In essence, the suggested defense against such a future was “Brush your teeth for democracy.” Or worse: “We are the guardians of oral and political hygiene—be more like us.” You slobs. It wasn’t a message endorsed by the Democratic Party or its handpicked candidate, Kamala Harris, who spent the final weeks of her abbreviated but competent campaign warning against the dangers of fascism. But it could have been.

It was an anxious summer. The American elections loomed, the sitting president had just been unmasked as an egomaniacal member of the walking undead, and here on the continent, across the Atlantic, Europe was about to elect the most right-wing parliament in the history of the European Union. The streets were plastered with campaign posters. In Germany, high over the boulevards, a well-known comedian gripped an enormous toothbrush and flashed her pearly whites. “Wählen ist wie Zähneputzen. Machst du’s nicht, wird’s braun!” read the accompanying text, or, “Voting is like brushing your teeth: don’t do it, and things’ll go brown.” The joke is that the Nazis wore brownshirts. To “go brown” is to go Nazi. In essence, the suggested defense against such a future was “Brush your teeth for democracy.” Or worse: “We are the guardians of oral and political hygiene—be more like us.” You slobs. It wasn’t a message endorsed by the Democratic Party or its handpicked candidate, Kamala Harris, who spent the final weeks of her abbreviated but competent campaign warning against the dangers of fascism. But it could have been. “Everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who almost went out with Ted Bundy.”

“Everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who almost went out with Ted Bundy.” Consider this straightforward calculation: (10100) + 1 – (10100)

Consider this straightforward calculation: (10100) + 1 – (10100) In a city well-known for political theater, the show at Stone Nest, a performance venue in the heart of London’s West End, took the concept to a new level. For the last month, audiences have been reenacting the events of Jan. 6, 2021, when a pro-Trump mob stormed the U.S. Capitol in one of the most violent and divisive days of modern American democracy. But instead of sitting in stately silence, legs crammed into velvet chairs, attendees at “Fight for America” were active participants — singing, chanting, rolling dice, and maneuvering tiny figurines around a model of the Capitol.

In a city well-known for political theater, the show at Stone Nest, a performance venue in the heart of London’s West End, took the concept to a new level. For the last month, audiences have been reenacting the events of Jan. 6, 2021, when a pro-Trump mob stormed the U.S. Capitol in one of the most violent and divisive days of modern American democracy. But instead of sitting in stately silence, legs crammed into velvet chairs, attendees at “Fight for America” were active participants — singing, chanting, rolling dice, and maneuvering tiny figurines around a model of the Capitol. Friday is the 30th anniversary of the deadliest massacre in Europe since World War II, when Bosnian Serb forces under Gen. Ratko Mladic overran an area meant to be protected by the United Nations. Soon after, they proceeded to

Friday is the 30th anniversary of the deadliest massacre in Europe since World War II, when Bosnian Serb forces under Gen. Ratko Mladic overran an area meant to be protected by the United Nations. Soon after, they proceeded to  In a 1989 interview with the Detroit Free Press, director Charlotte Zwerin worried that her documentary Thelonious Monk Straight, No Chaser, then newly out in general release after premiering the year before, would be labeled a “jazz film.” Zwerin had grown up, in the 1930s and ’40s, in Detroit, where she had heard a lot of jazz and become a lifelong fan of the music, yet she wanted audiences to see simply that Monk was “an American composer of tremendous stature” who “wrote beautiful songs.” Watching Straight, No Chaser today, you see just what she meant—calling this music jazz (or even American) somehow dilutes the once-in-a-millennium originality of songs that can be heard with the same jolt of immediacy and surprise in all times, places, and genres.

In a 1989 interview with the Detroit Free Press, director Charlotte Zwerin worried that her documentary Thelonious Monk Straight, No Chaser, then newly out in general release after premiering the year before, would be labeled a “jazz film.” Zwerin had grown up, in the 1930s and ’40s, in Detroit, where she had heard a lot of jazz and become a lifelong fan of the music, yet she wanted audiences to see simply that Monk was “an American composer of tremendous stature” who “wrote beautiful songs.” Watching Straight, No Chaser today, you see just what she meant—calling this music jazz (or even American) somehow dilutes the once-in-a-millennium originality of songs that can be heard with the same jolt of immediacy and surprise in all times, places, and genres. 1910: Lahore

1910: Lahore