Robert Bellafiore in The New Atlantis:

From Washington, D.C. to Silicon Valley, champions of new technologies often argue, with good reason, that we must embrace them because, if we don’t, the Chinese will — and then where will we be?

From Washington, D.C. to Silicon Valley, champions of new technologies often argue, with good reason, that we must embrace them because, if we don’t, the Chinese will — and then where will we be?

Driven by geopolitical pressures to accelerate technological development, particularly in AI and biotech, we seem to have two options: channeling innovation toward humane ends or protecting ourselves against competitors abroad.

To appreciate the difficulty of this choice, we should take a page from military theorists who have wrestled with what is known as the “security dilemma.” Even though it is one of the most important concepts in international relations, it has been given little attention by those grappling with the promises and challenges of new technologies. But we should, because when we apply its core insights to technological development, we realize that achieving a prosperous human future will be even more difficult than we tend to think.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Leftists argued, with considerable justification, that the MAGAworld response to neo-liberalism was little more than scapegoating where, to cite the Marxist geographer David Harvey, you “blame immigrants, foreign competition, in other words you blame everything except the underlying problems of capital because that is something which you’re allowed to talk about.” But in addition to these diversionary strategies, Trump won his second term in office promising to raise tariffs, bring manufacturing back to America, and defy international economic institutions. Despite his reassurances to powerful corporations that their profits would continue to grow, he managed to convince a sufficient number of aggrieved anti-globalist voters that he was on their side in the battle against unaccountable, unelected elites who sought to run the world on their terms.

Leftists argued, with considerable justification, that the MAGAworld response to neo-liberalism was little more than scapegoating where, to cite the Marxist geographer David Harvey, you “blame immigrants, foreign competition, in other words you blame everything except the underlying problems of capital because that is something which you’re allowed to talk about.” But in addition to these diversionary strategies, Trump won his second term in office promising to raise tariffs, bring manufacturing back to America, and defy international economic institutions. Despite his reassurances to powerful corporations that their profits would continue to grow, he managed to convince a sufficient number of aggrieved anti-globalist voters that he was on their side in the battle against unaccountable, unelected elites who sought to run the world on their terms. I

I I had the great good fortune to spend the entire month of May in Italy. And if you’ve heard the reports of people going there on vacation, eating their way through the country, and miraculously coming home a few pounds lighter, I’m here to tell you it doesn’t always work out that way. Those folks, though, often come home scratching their head about why Italians are so much thinner than Americans. And, when you go to Italy, or even read about going to Italy, it does make you wonder. They eat cookies for breakfast. Lunch and dinner are typically multicourse meals, with a pasta or risotto as a first course and a meat dish as a second. There are sometimes antipasti as well. Even

I had the great good fortune to spend the entire month of May in Italy. And if you’ve heard the reports of people going there on vacation, eating their way through the country, and miraculously coming home a few pounds lighter, I’m here to tell you it doesn’t always work out that way. Those folks, though, often come home scratching their head about why Italians are so much thinner than Americans. And, when you go to Italy, or even read about going to Italy, it does make you wonder. They eat cookies for breakfast. Lunch and dinner are typically multicourse meals, with a pasta or risotto as a first course and a meat dish as a second. There are sometimes antipasti as well. Even  If you ask a BaYaka Forager

If you ask a BaYaka Forager The narrative premises

The narrative premises Today marks the 50th anniversary of

Today marks the 50th anniversary of  Everybody likes ghazals. Or they do when they learn what they are: A ghazal is a poetic form originating in and strongly associated with the Islamic cultural sphere. It is a medieval thing—or what Westerners would call medieval. Many famous Persian poets are famous for their ghazals. Likewise, Arabic poets, Turkish, Urdu … The ready-to-hand comparison is with the Italian sonnet. Ghazals are a lot like that: song length, rhyme heavy, lots of lovey-doveyness, lots of over-the-top cosmic reasoning.

Everybody likes ghazals. Or they do when they learn what they are: A ghazal is a poetic form originating in and strongly associated with the Islamic cultural sphere. It is a medieval thing—or what Westerners would call medieval. Many famous Persian poets are famous for their ghazals. Likewise, Arabic poets, Turkish, Urdu … The ready-to-hand comparison is with the Italian sonnet. Ghazals are a lot like that: song length, rhyme heavy, lots of lovey-doveyness, lots of over-the-top cosmic reasoning. Mamdani didn’t have Cuomo’s money or institutional support, which may have freed him to run a transformative campaign. He didn’t shy away from his racial and religious identity, or from backing trans rights, or from supporting Palestine, and he didn’t have to because those positions are not inherently at odds with a “kitchen-table” campaign. He ran on affordability and championed meaningful economic proposals like universal child care and baby baskets, plus a rent freeze for regulated apartments. He told the obvious truth, which is that the city is crushing everyone who isn’t rich, and proposed solutions. With the laudatory assistance of Brad Lander, he modeled a new and more collaborative politics in contrast to Cuomo’s narcissism. He took that optimism to the streets and to social media with what seemed like boundless energy, and he redefined pragmatism for a new age in city politics. Maybe it’s radical to let child-care costs drive families out of the city. Maybe it’s Cuomo and his backers who are out of touch with real people.

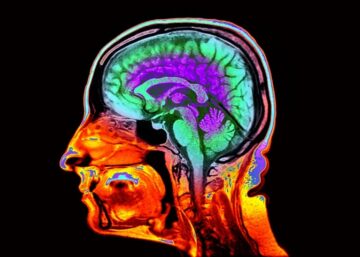

Mamdani didn’t have Cuomo’s money or institutional support, which may have freed him to run a transformative campaign. He didn’t shy away from his racial and religious identity, or from backing trans rights, or from supporting Palestine, and he didn’t have to because those positions are not inherently at odds with a “kitchen-table” campaign. He ran on affordability and championed meaningful economic proposals like universal child care and baby baskets, plus a rent freeze for regulated apartments. He told the obvious truth, which is that the city is crushing everyone who isn’t rich, and proposed solutions. With the laudatory assistance of Brad Lander, he modeled a new and more collaborative politics in contrast to Cuomo’s narcissism. He took that optimism to the streets and to social media with what seemed like boundless energy, and he redefined pragmatism for a new age in city politics. Maybe it’s radical to let child-care costs drive families out of the city. Maybe it’s Cuomo and his backers who are out of touch with real people. Telltale features visible in standard brain images can reveal

Telltale features visible in standard brain images can reveal  Take a look at this video of a waiting room. Do you see anything strange?

Take a look at this video of a waiting room. Do you see anything strange? The global economy is getting a hardware refit and trying out a new operating system—in effect, a full reboot, the likes of which we have not seen in nearly a century. To understand why this is happening and what it means, we need to abandon any illusion that the worldwide turn toward right-wing populism and economic nationalism is merely a temporary error, and that everything will eventually snap back to the relatively benign world of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The computer’s architecture is changing, but how this next version of capitalism will work depends a great deal on the software we choose to run on it. The governing ideas about the economy are in flux: We have to decide what the new economic order looks like and whose interests it will serve.

The global economy is getting a hardware refit and trying out a new operating system—in effect, a full reboot, the likes of which we have not seen in nearly a century. To understand why this is happening and what it means, we need to abandon any illusion that the worldwide turn toward right-wing populism and economic nationalism is merely a temporary error, and that everything will eventually snap back to the relatively benign world of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The computer’s architecture is changing, but how this next version of capitalism will work depends a great deal on the software we choose to run on it. The governing ideas about the economy are in flux: We have to decide what the new economic order looks like and whose interests it will serve. T

T