Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Can We Trust Social Science Yet?

Ryan Briggs at Asterisk:

Ideally, policy and program design is a straightforward process: a decision-maker faces a problem, turns to peer-reviewed literature, and selects interventions shown to work. In reality, that’s rarely how things unfold. The popularity of “evidence-based medicine” and other “evidence-based” topics highlights our desire for empirical approaches — but would the world actually improve if those in power consistently took social science evidence seriously? It brings me no joy to tell you that, at present, I think the answer is usually “no.”

Ideally, policy and program design is a straightforward process: a decision-maker faces a problem, turns to peer-reviewed literature, and selects interventions shown to work. In reality, that’s rarely how things unfold. The popularity of “evidence-based medicine” and other “evidence-based” topics highlights our desire for empirical approaches — but would the world actually improve if those in power consistently took social science evidence seriously? It brings me no joy to tell you that, at present, I think the answer is usually “no.”

Given the current state of evidence production in the social sciences, I believe that many — perhaps most — attempts to use social scientific evidence to inform policy will not lead to better outcomes. This is not because of politics or the challenges of scaling small programs. The problem is more immediate. Much of social science research is of poor quality, and sorting the trustworthy work from bad work is difficult, costly, and time-consuming.

But it is necessary.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Fossils reveal secrets about the mysterious humans

Michael Marshall in Nature:

It was the finger seen around the world. In 2008, archaeologists working in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia, Russia, uncovered a tiny bone: the tip of the little finger of an ancient human that lived there tens of thousands of years ago. The fragment didn’t seem remarkable, but it was well preserved, giving researchers hope that it harboured intact DNA. A team of geneticists led by Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, removed 30 milligrams of bone and managed to extract enough intact DNA to analyse it. They were able to sequence the entire mitochondrial genome — and were shocked by what they found. The DNA did not match that of modern humans, or of Neanderthals, the other likely candidate1. It was a new population, which they dubbed the Denisovans, after the cave.

It was the finger seen around the world. In 2008, archaeologists working in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia, Russia, uncovered a tiny bone: the tip of the little finger of an ancient human that lived there tens of thousands of years ago. The fragment didn’t seem remarkable, but it was well preserved, giving researchers hope that it harboured intact DNA. A team of geneticists led by Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, removed 30 milligrams of bone and managed to extract enough intact DNA to analyse it. They were able to sequence the entire mitochondrial genome — and were shocked by what they found. The DNA did not match that of modern humans, or of Neanderthals, the other likely candidate1. It was a new population, which they dubbed the Denisovans, after the cave.

When the team announced this result in March 2010, it caused a sensation. Up to that point, researchers had used preserved bones to identify every species or population of hominin — the group that includes modern and ancient humans and their immediate ancestors. “Denisovans were created from DNA work,” says palaeoanthropologist Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum in London. Nine months later came the second bombshell. Krause and his colleagues had obtained the entire nuclear genome from the finger bone, which yielded much more information. It showed that the Denisovans were a sister group to the Neanderthals, which lived in Europe and western Asia for hundreds of thousands of years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

What Have I Learned

What have I learned but

the proper use for several tools?

The moments

between hard pleasant tasks

To sit silent, drink wine,

and think my own kind

of dry crusty thoughts.

—the first Calochortus flowers

and in all the land,

it’s spring.

I point them out:

the yellow petals, the golden hairs,

to Gen.

Seeing in silence:

never the same twice,

but when you get it right,

you pass it on.

by Gary Snyder

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

9 Federally Funded Scientific Breakthroughs That Changed Everything

Alan Burdick et al in The New York Times:

![]() Science seldom works in straight lines. Sometimes it’s “applied” to solve specific problems: Let’s put people on the moon; we need a Covid vaccine. Much of the time it’s “basic,” aimed at understanding, say, cell division or the physics of cloud formation, with the hope that — somehow, someday — the knowledge will prove useful. Basic science is applied science that hasn’t been applied yet.

Science seldom works in straight lines. Sometimes it’s “applied” to solve specific problems: Let’s put people on the moon; we need a Covid vaccine. Much of the time it’s “basic,” aimed at understanding, say, cell division or the physics of cloud formation, with the hope that — somehow, someday — the knowledge will prove useful. Basic science is applied science that hasn’t been applied yet.

That’s the premise on which the United States, since World War II, has invested heavily in science. The government spends $200 billion annually on research and development, knowing that payoffs might be decades away; that figure would drop sharply under President Trump’s proposed 2026 budget. “Basic research is the pacemaker of technological progress,” Vannevar Bush, who laid out the postwar schema for government research support, wrote in a 1945 report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Look no further than Google, which got its start in 1994 with a $4 million federal grant to help build digital libraries; the company is now a $2 trillion verb.

Here are nine more life-altering advances that government investment made possible.

GPS

The first commercial GPS unit, a $3,000 brick for hikers and boaters, was made in 1988. The technology is now so ubiquitous — in cars, planes, phones, smartwatch running apps — that its existence can seem almost preordained.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, May 19, 2025

The Fabricated Crisis of Art Criticism

Hakim Bishara at Hyperallergic:

Art criticism is thriving. It’s taking on new forms, shedding old skin, and adapting to novel venues. It’s as alive and relevant as ever, still generating conversation and controversy. Instead of fizzling out, it’s being embraced by new generations of critics, whether in these pages or on Substack, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok (no matter the platform, it always comes down to writing). It’s a buzzing genre that attracts readers of all ages, from septum-pierced college students to cigar-puffing art collectors.

Art criticism is thriving. It’s taking on new forms, shedding old skin, and adapting to novel venues. It’s as alive and relevant as ever, still generating conversation and controversy. Instead of fizzling out, it’s being embraced by new generations of critics, whether in these pages or on Substack, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok (no matter the platform, it always comes down to writing). It’s a buzzing genre that attracts readers of all ages, from septum-pierced college students to cigar-puffing art collectors.

Yes, gone are the days when an insular clique of critics had the ability to make or break artists’ careers — and good riddance. That was more power than anybody deserves. The quality of a critic’s work now carries more weight than their cult of personality. That’s not a bad thing. Insightful, incisive, and inventive writing will always have a future and an audience. So long as there’s art, there will be art criticism.

Art criticism is not in crisis. Good art criticism is the crisis.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

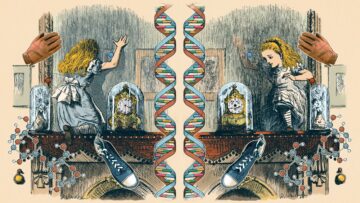

How the Universe Differs From Its Mirror Image

Zack Savitsky in Quanta:

After her adventures in Wonderland, the fictional Alice stepped through the mirror above her fireplace in Lewis Carroll’s 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass to discover how the reflected realm differed from her own. She found that the books were all written in reverse, and the people were “living backwards,” navigating a world where effects preceded their causes.

After her adventures in Wonderland, the fictional Alice stepped through the mirror above her fireplace in Lewis Carroll’s 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass to discover how the reflected realm differed from her own. She found that the books were all written in reverse, and the people were “living backwards,” navigating a world where effects preceded their causes.

When objects appear different in the mirror, scientists call them chiral. Hands, for instance, are chiral. Imagine Alice trying to shake hands with her reflection. A right hand in mirror-world becomes a left hand, and there’s no way to align the two perfectly for a handshake because the fingers bend the wrong way. (In fact, the word “chirality” originates from the Greek word for “hand.”)

Alice’s experience reflects something deep about our own universe: Everything is not the same through the looking glass. The behavior of many familiar objects, from molecules to elementary particles, depends on which mirror-image version we interact with.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tech mogul Palmer Luckey creating arsenal of AI-powered autonomous weapons

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The sharp decline in young Americans’ support for free speech

Jacob Mchangama in The Conversation:

For much of the 20th century, young Americans were seen as free speech’s fiercest defenders. But now, young Americans are growing more skeptical of free speech.

For much of the 20th century, young Americans were seen as free speech’s fiercest defenders. But now, young Americans are growing more skeptical of free speech.

According to a March 2025 report by The Future of Free Speech, a nonpartisan think tank where I am executive director, support among 18- to 34-year-olds for allowing controversial or offensive speech has dropped sharply in recent years.

In 2021, 71% of young Americans said people should be allowed to insult the U.S. flag, which is a key indicator of support for free speech, no matter how distasteful. By 2024, that number had fallen to just 43% – a 28-point drop. Support for pro‑LGBTQ+ speech declined by 20 percentage points, and tolerance for speech that offends religious beliefs fell by 14 points.

This drop contributed to the U.S. having the third-largest decline in free speech support among the 33 countries that The Future of Free Speech surveyed – behind only Japan and Israel.

Why has this support diminished so dramatically?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What My Two 98-Year-Old Patients Taught Me About Longevity

Eric Topol in Time Magazine:

Meet my patient Mrs. L. R. She’s 98 years young and has never suffered a day of serious illness in her long life. She was referred to me by her primary care physician to assess her heart condition because she had developed swelling in her legs, known as edema. When we first met in the clinic, I noted there was no accompanying family member, so I asked how she got to the medical center. She’d driven herself. I soon learned much more about this exceptionally vibrant, healthy lady who lives alone, has an extensive social network, and enjoys her solitude.

Meet my patient Mrs. L. R. She’s 98 years young and has never suffered a day of serious illness in her long life. She was referred to me by her primary care physician to assess her heart condition because she had developed swelling in her legs, known as edema. When we first met in the clinic, I noted there was no accompanying family member, so I asked how she got to the medical center. She’d driven herself. I soon learned much more about this exceptionally vibrant, healthy lady who lives alone, has an extensive social network, and enjoys her solitude.

Her remarkable health span isn’t shared by her family members. Her mother died at 59; her father at 64. Her two brothers died at 43 and 75. Three years prior to our meeting, her husband had died at 97. He had also been quite healthy, with a similar health span profile in contrast to his parents and siblings, who all had chronic diseases and died decades younger. Following her husband’s death, Mrs. L. R. got depressed and dropped 30 pounds. She lost her interest in her hobbies of painting and doing 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzles. She did continue to play cards and Rummikub every week with a circle of eight women. One of these friends suggested she move from the house she’d lived in for decades to a senior residence apartment. The move led her to artists, new friends, and an extended social network. This all brought her back to her “old” self, fully restoring her life’s passions and getting back to a healthy weight.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Year the Leaf-Cutter Ants Took Manhattan

Emily Anthes in The New York Times:

It was a cold, gray afternoon in December, and at the American Museum of Natural History, a half million leaf-cutter ants were hunkered down in their homes. The ants typically spend their days harvesting slivers of leaves, which they use to grow expansive fungal gardens that serve as both food and shelter. On many days, visitors to the museum’s insectarium can watch an endless river of ants transporting leaf fragments from the foraging area to the fungus-filled glass orbs where they live.

It was a cold, gray afternoon in December, and at the American Museum of Natural History, a half million leaf-cutter ants were hunkered down in their homes. The ants typically spend their days harvesting slivers of leaves, which they use to grow expansive fungal gardens that serve as both food and shelter. On many days, visitors to the museum’s insectarium can watch an endless river of ants transporting leaf fragments from the foraging area to the fungus-filled glass orbs where they live.

It was hard to blame them. It was a biting, blustery day — and the end of a long, eventful year for the colony. The tropical ants, which had been harvested in Trinidad and nurtured in Oregon, had never set foot in New York City before last December, arriving like 500,000 insect ingénues. It took time for the ants to find their footing and for museum employees to learn how to create a happy home for them.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, May 18, 2025

How to make bureaucracies better

Nicola Jones in Knowable Magazine:

What is the history of bureaucracies? Where did the concept originate, and how has it evolved?

What is the history of bureaucracies? Where did the concept originate, and how has it evolved?

It’s always been true that ideas and policies don’t execute themselves. You need a bureaucracy, a group of servants, to do that for you. That is true for nation states, and also for companies and universities.

The major leap in the evolution of bureaucracy, to a place that is not corrupt, happens when the people appointed to it aren’t friends or family or political cronies who can pay for their position, but people who are selected for their expertise, meritocratically. If you go back more than a thousand years, China is one of the first places where we see the development of a really important bureaucracy with entrance exams. It was very serious if you were caught cheating — the punishment could be death. We know from ample literature that corruption is lower where you have meritocratically recruited civil servants.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

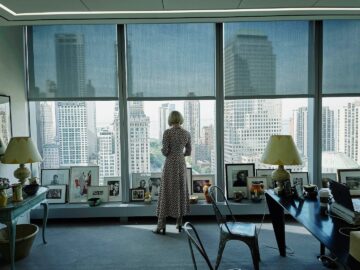

Anna Wintour becomes an unlikely activist as Washington quashes DEI

Robin Givhan in The Washington Post:

Wintour is the longtime editor in chief of Vogue and the chief content officer for the publishing behemoth Condé Nast, whose stable of magazines includes Bon Appetit, Teen Vogue and New Yorker. She is the mastermind behind the Met Gala, which lit up the pop culture cosmos earlier this month. In many respects, Wintour, at 75, remains the most recognizable face of the fashion establishment. But fashion, at the level where Wintour has long served as gatekeeper, and with its subjective assessment of aesthetics, has struggled more than most industries with diversity and inclusivity, from the pages of its magazines to its corporate boardrooms. And despite moments of intense focus on racial justice, big changes have often been superficial and real change has been slow.

Wintour is the longtime editor in chief of Vogue and the chief content officer for the publishing behemoth Condé Nast, whose stable of magazines includes Bon Appetit, Teen Vogue and New Yorker. She is the mastermind behind the Met Gala, which lit up the pop culture cosmos earlier this month. In many respects, Wintour, at 75, remains the most recognizable face of the fashion establishment. But fashion, at the level where Wintour has long served as gatekeeper, and with its subjective assessment of aesthetics, has struggled more than most industries with diversity and inclusivity, from the pages of its magazines to its corporate boardrooms. And despite moments of intense focus on racial justice, big changes have often been superficial and real change has been slow.

Five years ago, during the powerful sweep of the Black Lives Matter movement, editors, designers, stylists and others within the fashion industry were emboldened to confront the powers-that-be with a list of outrages that included pay inequity and assertions that they were actively disrespected in their workplace.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Sacrifice

he was still

wet

her Hindu

amniotic fluid

on his new

Pakistani body.

two days or

two kilometers that way

he would have been Indian

but the border had been drawn

by white hands

and swords had been drawn

by brown ones.

either way, he was

and now, wasn’t.

she called him Yousuf—

the name my Muslim grandfather

would have given him

pulled out his tiny body

from between her legs

stumbled into the darkness

far away from the camps

dug a hole with bare hands

and placed him in his cradle.

the next night, wolves

looted the earth.

by Ain Kahn

from Rattle Magazine

Author’s note:

“I grew up with stories of the Partition of India, and the trauma and heartbreak it inflicted upon millions, including both sets of my grandparents. I am struck by the continued sacrifices and loss of lives required to uphold the identities of these two nations, which share so many social, cultural, linguistic and artistic commonalities, because they were at one point, one.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, May 16, 2025

The Contagion of Everyday Life

Jeannette Cooperman at The Common Reader:

A pandemic is never only about biological contagion. Much of what we feel, think, and do—far more than I want to admit—is the product of what we perceive or unconsciously mimic in the world around us. Laughter is contagious, and yawns—even chimpanzees find yawns contagious. I realize only now, in the enforced quiet, how I absorbed the pace and values of the society around me. My mind was quiet, if concerned, as I watched the infectiousness of fear, panic, and hysteria; of rationalization or mystification; of courage. Ideas and beliefs, good information and bad information, enthusiasm and advice and funny memes spread as fast as the virus.

A pandemic is never only about biological contagion. Much of what we feel, think, and do—far more than I want to admit—is the product of what we perceive or unconsciously mimic in the world around us. Laughter is contagious, and yawns—even chimpanzees find yawns contagious. I realize only now, in the enforced quiet, how I absorbed the pace and values of the society around me. My mind was quiet, if concerned, as I watched the infectiousness of fear, panic, and hysteria; of rationalization or mystification; of courage. Ideas and beliefs, good information and bad information, enthusiasm and advice and funny memes spread as fast as the virus.

All of that is contagion.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

DeepMind unveils ‘spectacular’ general-purpose science AI

Elizabeth Gibney in Nature:

The system, called AlphaEvolve, combines the creativity of a large language model (LLM) with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. It was described in a white paper released by the company on 14 May.

The system, called AlphaEvolve, combines the creativity of a large language model (LLM) with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. It was described in a white paper released by the company on 14 May.

“The paper is quite spectacular,” says Mario Krenn, who leads the Artificial Scientist Lab at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light in Erlangen, Germany. “I think AlphaEvolve is the first successful demonstration of new discoveries based on general-purpose LLMs.”

As well as using the system to discover solutions to open maths problems, DeepMind has already applied the artificial intelligence (AI) technique to its own practical challenges, says Pushmeet Kohli, head of science at the firm in London.

AlphaEvolve has helped to improve the design of the company’s next generation of tensor processing units — computing chips developed specially for AI — and has found a way to more efficiently exploit Google’s worldwide computing capacity, saving 0.7% of total resources. “It has had substantial impact,” says Kohli.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Exploring The Supercar Junkyards of Dubai

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Beyond Hyperpolitics

Oliver Eagleton at The Ideas Letter:

One of the most intriguing ways of conceptualizing the scorched landscape of the 2020s is the theory of ‘hyperpolitics’, advanced by the Belgian political philosopher Anton Jäger. Our current predicament, he writes, is one of “extreme politicization without political consequences.” While ideological commitment is ubiquitous, institutional outlets for it are absent. While contestation is fierce, the form it takes is frustratingly ephemeral. Politics is at once everywhere and nowhere – permeating our everyday lives but failing to influence state policy, which continues on much the same neoliberal trajectory, with minor variations here and there.

One of the most intriguing ways of conceptualizing the scorched landscape of the 2020s is the theory of ‘hyperpolitics’, advanced by the Belgian political philosopher Anton Jäger. Our current predicament, he writes, is one of “extreme politicization without political consequences.” While ideological commitment is ubiquitous, institutional outlets for it are absent. While contestation is fierce, the form it takes is frustratingly ephemeral. Politics is at once everywhere and nowhere – permeating our everyday lives but failing to influence state policy, which continues on much the same neoliberal trajectory, with minor variations here and there.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

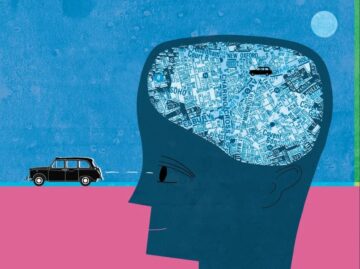

Why Taxi Drivers Don’t Die of Alzheimer’s

Erin O’Donnell in Harvard Magazine:

London cabbies are famous for knowing their way around their city’s maze of streets. To obtain a taxi license in London, drivers must pass a legendary test requiring them to memorize the names and locations of 25,000 streets, as well as landmarks and businesses. Passing the exam demands years of intensive study.

London cabbies are famous for knowing their way around their city’s maze of streets. To obtain a taxi license in London, drivers must pass a legendary test requiring them to memorize the names and locations of 25,000 streets, as well as landmarks and businesses. Passing the exam demands years of intensive study.

This knowledge appears to affect the drivers’ brains, enlarging the hippocampus, an area responsible for spatial memory and navigation. According to a small brain-imaging study published in 2000, London cab drivers had unusually large hippocampi. This part of the brain also happens to degrade in people with Alzheimer’s disease. With those findings in mind, four Harvard researchers recently conducted a new study, published in the BMJ (formerly known as the British Medical Journal), which explored rates of Alzheimer’s-related deaths among almost nine million people across 443 different occupations between 2020 and 2022.

“The two occupations with the lowest Alzheimer’s mortality are ambulance drivers and taxi drivers, jobs that very heavily use the hippocampus as a function of their everyday work,” explains Newhouse professor of healthcare policy Anupam Jena. He and his colleagues were startled by the strength of their results: ambulance drivers and taxi drivers were less than half as likely to die of Alzheimer’s disease than the general population.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘Original Sin’ indicts the ‘cover-up’ of a steeply declining Joe Biden

Alex Shephard in The Washington Post:

In April 2024, Favreau visited the White House with his podcast co-hosts and several other “influencers” at a meet-and-greet the night before the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Biden was incoherent and frail; he kept telling stories that no one could understand. Sixteen months had passed, but he seemed to have aged a half-century. An alarmed Favreau approached a White House aide, but his concerns were brushed off. The president was just tired, he was told. It was the end of a long week. There was no reason for concern. Two months later, Biden delivered the single worst performance in the 60-year history of televised presidential debates, dooming his reelection campaign, destroying his presidency and essentially delivering the country to Donald Trump.

In April 2024, Favreau visited the White House with his podcast co-hosts and several other “influencers” at a meet-and-greet the night before the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Biden was incoherent and frail; he kept telling stories that no one could understand. Sixteen months had passed, but he seemed to have aged a half-century. An alarmed Favreau approached a White House aide, but his concerns were brushed off. The president was just tired, he was told. It was the end of a long week. There was no reason for concern. Two months later, Biden delivered the single worst performance in the 60-year history of televised presidential debates, dooming his reelection campaign, destroying his presidency and essentially delivering the country to Donald Trump.

Favreau’s experience was hardly unique. Far from it. “Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again,” CNN anchor Jake Tapper and Axios reporter Alex Thompson’s account of Biden’s marked deterioration throughout his presidency, is littered with similar anecdotes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.