Jessie Morgan-Owens in Smithsonian Magazine:

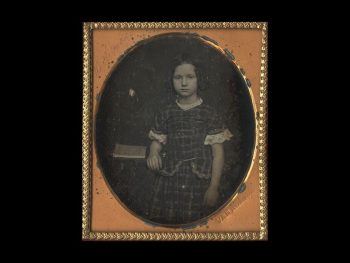

On February 19, 1855, Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator, wrote his supporters about an enslaved 7-year-old girl whose freedom he had helped to secure. She would be joining him onstage at an abolitionist lecture that spring. “I think her presence among us (in Boston) will be a great deal more effective than any speech I could make,” the noted orator wrote. He said her name was Mary, but he also referred to her, significantly, as “another Ida May.” Sumner enclosed a daguerreotype of Mary standing next to a small table with a notebook at her elbow. She is neatly outfitted in a plaid dress, with a solemn expression on her face, and looks for all the world like a white girl from a well-to-do family.

On February 19, 1855, Charles Sumner, the Massachusetts senator, wrote his supporters about an enslaved 7-year-old girl whose freedom he had helped to secure. She would be joining him onstage at an abolitionist lecture that spring. “I think her presence among us (in Boston) will be a great deal more effective than any speech I could make,” the noted orator wrote. He said her name was Mary, but he also referred to her, significantly, as “another Ida May.” Sumner enclosed a daguerreotype of Mary standing next to a small table with a notebook at her elbow. She is neatly outfitted in a plaid dress, with a solemn expression on her face, and looks for all the world like a white girl from a well-to-do family.

When the Boston Telegraph published Sumner’s letter, it caused a sensation. Newspapers from Maine to Washington, D.C. picked up on the story of the “white slave from Virginia,” and paper copies of the daguerreotype were sold alongside a broadsheet promising the “History of Ida May.”

The name referred to the title character of Ida May: A Story of Things Actual and Possible, a thrilling novel, published just three months earlier, about a white girl who was kidnapped on her fifth birthday, beaten unconscious and sold across state lines into slavery. The author, Mary Hayden Green Pike, was an abolitionist, and her tale was calculated to arouse white Northerners to oppose slavery and to resist the Fugitive Slave Act, the five-year-old federal law demanding that suspected slaves be returned to their masters. Pike’s story fanned fears that the law threatened both black and white children, who, once enslaved, might be difficult to legally recover.

It was shrewd of Sumner to link the outrage stirred by the fictional Ida May to the plight of the real Mary—a brilliant piece of propaganda that turned Mary into America’s first poster child. But Mary hadn’t been kidnapped; she was born into slavery.

More here.