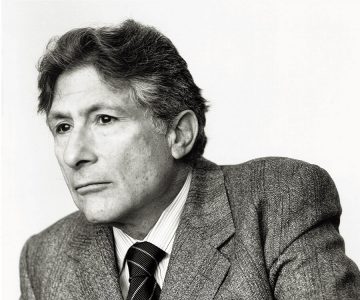

Robert Reich in The Guardian:

What is America really fighting over in the upcoming election? Not any particular issue. Not even Democrats versus Republicans. The central fight is over Donald J Trump. Before Trump, most Americans weren’t especially passionate about politics. But Trump’s MO has been to force people to become passionate about him – to take fierce sides for or against. And he considers himself president only of the former, whom he calls “my people”. Trump came to office with no agenda except to feed his monstrous ego. He has never fueled his base. His base has fueled him. Its adoration sustains him. So does the antipathy of his detractors. Presidents usually try to appease their critics. Trump has gone out of his way to offend them. “I do bring rage out,” he unapologetically told Bob Woodward in 2016.

What is America really fighting over in the upcoming election? Not any particular issue. Not even Democrats versus Republicans. The central fight is over Donald J Trump. Before Trump, most Americans weren’t especially passionate about politics. But Trump’s MO has been to force people to become passionate about him – to take fierce sides for or against. And he considers himself president only of the former, whom he calls “my people”. Trump came to office with no agenda except to feed his monstrous ego. He has never fueled his base. His base has fueled him. Its adoration sustains him. So does the antipathy of his detractors. Presidents usually try to appease their critics. Trump has gone out of his way to offend them. “I do bring rage out,” he unapologetically told Bob Woodward in 2016.

In this way, he has turned America into a gargantuan projection of his own pathological narcissism. His entire re-election platform is found in his use of the pronouns “we” and “them”. “We” are people who love him, Trump Nation. “They” hate him. In late August, near the end of a somnolent address on the South Lawn of the White House, accepting the Republican nomination, Trump extemporized: “The fact is, we’re here – and they’re not.” It drew a standing ovation. At a recent White House news conference, a CNN correspondent asked if Trump condemned the behavior of his supporters in Portland, Oregon. In response, he charged: “Your supporters, and they are your supporters indeed, shot a young gentleman.”

In Trump’s eyes, CNN exists in a different country: Anti-Trump Nation.

More here.

Katrina vanden Heuvel in The Nation:

Katrina vanden Heuvel in The Nation: Sweet Dreams tactfully sidesteps whether some of the New Romantics mirrored the celebrity-for-celebrity’s sake aspirations of many of today’s vloggers and influencers. But Jones makes a convincing case that their penchant for what used to be called “gender-bending” and their sartorial obsession with self-expression as “a platform for identity” foreshadows a lot of 2020’s hot-button topics. The book is excellent on the movement’s origins both in the aspirational teenage style cult that built around Bryan Ferry in the mid-70s and the more fashion-forward occupants of the same era’s gay clubs and soul nights, who saw the clothes Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold in their boutique Sex not as harbingers of spittle-flecked youth revolution but as a particularly outrageous brand of couture: it’s often written out of punk’s history that, at precisely the same time the Sex Pistols’ career was getting underway, there were people in Essex dancing to disco dressed exactly like Johnny Rotten.

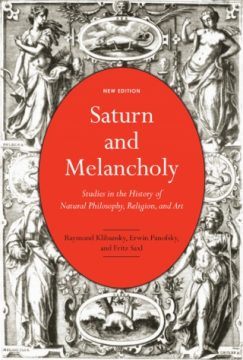

Sweet Dreams tactfully sidesteps whether some of the New Romantics mirrored the celebrity-for-celebrity’s sake aspirations of many of today’s vloggers and influencers. But Jones makes a convincing case that their penchant for what used to be called “gender-bending” and their sartorial obsession with self-expression as “a platform for identity” foreshadows a lot of 2020’s hot-button topics. The book is excellent on the movement’s origins both in the aspirational teenage style cult that built around Bryan Ferry in the mid-70s and the more fashion-forward occupants of the same era’s gay clubs and soul nights, who saw the clothes Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold in their boutique Sex not as harbingers of spittle-flecked youth revolution but as a particularly outrageous brand of couture: it’s often written out of punk’s history that, at precisely the same time the Sex Pistols’ career was getting underway, there were people in Essex dancing to disco dressed exactly like Johnny Rotten. If melancholia may be “[s]ometimes painful and depressing, sometimes merely mildly pensive or nostalgic,” then this new edition is, in its own right, a melancholic exercise, a wistful homage to the once-world in which the book was produced. It is also melancholic from the perspective of the contemporary reader who is able to fathom the shear catholicity of mind necessary to produce a Meisterwerk of this sort. But it is in fact that very nostalgia that is in question in the book proper, for the study lays out just how persistently the posture of scholar, artist and anchorite alike has been one of despair at the path that separates them from the great transcendence lying on the horizon, whether that goes by the name of God, the eternal intellect or the Mallarmean “Book.” And in this respect, the history of melancholy itself joins up with the story of the long, arduous path by which the book came into being.

If melancholia may be “[s]ometimes painful and depressing, sometimes merely mildly pensive or nostalgic,” then this new edition is, in its own right, a melancholic exercise, a wistful homage to the once-world in which the book was produced. It is also melancholic from the perspective of the contemporary reader who is able to fathom the shear catholicity of mind necessary to produce a Meisterwerk of this sort. But it is in fact that very nostalgia that is in question in the book proper, for the study lays out just how persistently the posture of scholar, artist and anchorite alike has been one of despair at the path that separates them from the great transcendence lying on the horizon, whether that goes by the name of God, the eternal intellect or the Mallarmean “Book.” And in this respect, the history of melancholy itself joins up with the story of the long, arduous path by which the book came into being.

Radhika Coomaraswamy in Daily FT (Sri Lanka):

Radhika Coomaraswamy in Daily FT (Sri Lanka): I

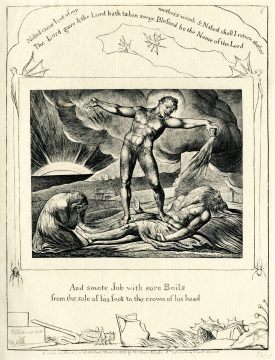

I I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss? In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection

I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss? In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection

Estimates of the proportion of people who die from Covid-19 have been controversial, with some even dismissing it as similar to a bad flu. There are three main problems accounting for this controversy.

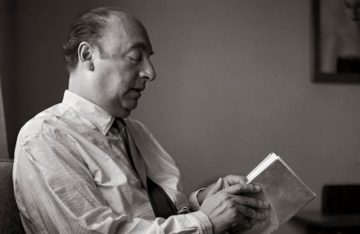

Estimates of the proportion of people who die from Covid-19 have been controversial, with some even dismissing it as similar to a bad flu. There are three main problems accounting for this controversy. My love for your poetry is complicated further, because the memory of a Tamil woman called Thangamma keeps casting a dark shadow of fear and menace over your work. She darts and dives between the lines of your poems with an angry, restless spirit that will not cease.

My love for your poetry is complicated further, because the memory of a Tamil woman called Thangamma keeps casting a dark shadow of fear and menace over your work. She darts and dives between the lines of your poems with an angry, restless spirit that will not cease.