Jackson Arn in The Point:

For good reason, The Great Gatsby is one of the most admired and talked-about books of the twentieth century. And that reason is, of course, that it’s really short—47,094 words, to be exact. I read it for the first time in a few hours at a swim meet (the aptness of the setting wasn’t clear to me until Chapter 8) and probably would have finished sooner had it not been for the snatches of Eminem coming from somebody’s boombox. You can count the book’s speaking roles on your fingers, and any high school sophomore can skim it the night before the big exam. Assign that to millions of teenagers for sixty-odd years, and a Great American Novel is born.

For good reason, The Great Gatsby is one of the most admired and talked-about books of the twentieth century. And that reason is, of course, that it’s really short—47,094 words, to be exact. I read it for the first time in a few hours at a swim meet (the aptness of the setting wasn’t clear to me until Chapter 8) and probably would have finished sooner had it not been for the snatches of Eminem coming from somebody’s boombox. You can count the book’s speaking roles on your fingers, and any high school sophomore can skim it the night before the big exam. Assign that to millions of teenagers for sixty-odd years, and a Great American Novel is born.

I don’t mean to belittle what Fitzgerald achieved in his most famous work: the grandeur of his themes, or the calm thrust of his narrator’s voice, or the fine shading of his descriptions (the bit about the juice machine button pressed two hundred times by a butler’s thumb has mocked my feeble attempts at lyricism for years). But not all beautifully written books sell half a million copies a year, and it’s no coincidence that Gatsby—rather than The Adventures of Augie March, Invisible Man or Gravity’s Rainbow, to name three American novels of equal splendor but considerably more bulk—is the rare classic that everyone remembers the gist of. There is much less of it to forget.

So much less, in fact, that readers may find themselves remembering things Fitzgerald never wrote.

More here.

What is it about the proposal that strikes me as so disturbing?’ Reading through an article describing a local government measure, I feel opposition rising within me. Normally, forming an opinion about such things would take me some time. But not here. The proposal instantly strikes me as unjust. My reaction is not just intellectual; it is visceral. My emotions are engaged. My imagination is exercised. As I imagine the proposal playing out in practice, the distinctive brand of injustice seems to be jumping out of every word on the page.

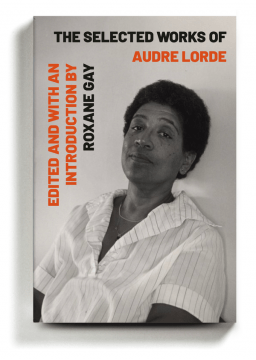

What is it about the proposal that strikes me as so disturbing?’ Reading through an article describing a local government measure, I feel opposition rising within me. Normally, forming an opinion about such things would take me some time. But not here. The proposal instantly strikes me as unjust. My reaction is not just intellectual; it is visceral. My emotions are engaged. My imagination is exercised. As I imagine the proposal playing out in practice, the distinctive brand of injustice seems to be jumping out of every word on the page. Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.”

Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.” Adam Tooze in The Guardian:

Adam Tooze in The Guardian: Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET:

Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET: Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books:

Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books: Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America. In 2014, Kate Livingston

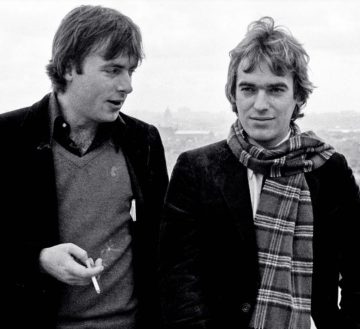

In 2014, Kate Livingston  It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious.

It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious. In the 1940s, trailblazing physicists stumbled upon the next layer of reality. Particles were out, and fields — expansive, undulating entities that fill space like an ocean — were in. One ripple in a field would be an electron, another a photon, and interactions between them seemed to explain all electromagnetic events.

In the 1940s, trailblazing physicists stumbled upon the next layer of reality. Particles were out, and fields — expansive, undulating entities that fill space like an ocean — were in. One ripple in a field would be an electron, another a photon, and interactions between them seemed to explain all electromagnetic events. Every year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation releases a Goalkeepers report, tracking the world’s progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. The news is almost always pretty good. This year’s edition is … not like that. “Almost every time we have opened our mouths or put pen to paper,” the Gateses write in the report’s introduction, “we have celebrated decades of historic progress in fighting poverty and disease. But we have to confront the current reality with candor: This progress has now stopped.” Their annual report tracks global progress on 18 different metrics. “In recent years, the world has improved on every single one. This year, on the vast majority, we’ve regressed.”

Every year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation releases a Goalkeepers report, tracking the world’s progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. The news is almost always pretty good. This year’s edition is … not like that. “Almost every time we have opened our mouths or put pen to paper,” the Gateses write in the report’s introduction, “we have celebrated decades of historic progress in fighting poverty and disease. But we have to confront the current reality with candor: This progress has now stopped.” Their annual report tracks global progress on 18 different metrics. “In recent years, the world has improved on every single one. This year, on the vast majority, we’ve regressed.”