Category: Recommended Reading

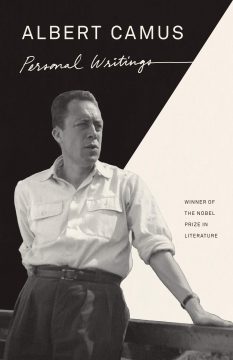

For Camus, It Was Always Personal

Robert Zaretsky at the LARB:

In her sharp and sympathetic foreword, Alice Kaplan observes that, for readers who know Camus only as the author of The Stranger, the “lush emotional intensity of these early essays and stories will come as a surprise.” Yet I confess that, even for someone who knew this side of Camus, I was again, as I reread the pieces, surprised by their Dionysian intensity.

In her sharp and sympathetic foreword, Alice Kaplan observes that, for readers who know Camus only as the author of The Stranger, the “lush emotional intensity of these early essays and stories will come as a surprise.” Yet I confess that, even for someone who knew this side of Camus, I was again, as I reread the pieces, surprised by their Dionysian intensity.

The lyricism is especially bracing today, when even Dionysus would think twice before throwing a bacchanalia. For Camus, the lyrical sentiments were deeply rooted in the physical and human landscape of his native Algeria. They flowed from the childhood he spent in a poor neighborhood of Algiers, where he was raised by an illiterate and imperious grandmother and a deaf and mostly mute mother in a sagging two-story building, whose cockroach-infested stairwell led to a common latrine on the landing.

more here.

The Many Faces of Ethan Hawke

John Lahr at The New Yorker:

Throughout his career, Hawke has consistently challenged himself to grow. He has appeared in more than eighty movies, predominantly independent films interspersed with Hollywood money-makers. He has directed four films, written three novels, and co-founded a theatre company. In the process, Hawke has been nominated for four Academy Awards (including two for Best Adapted Screenplay) and a Tony, for his performance, in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy “The Coast of Utopia,” as Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary Russian anarchist, whose bowwow personality resurfaces in the fulminations of Hawke’s John Brown. The range of Hawke’s roles—a romantic charmer (in the “Before” trilogy), a drug-addled Chet Baker (in “Born to Be Blue”), a guilt-ridden suicidal priest (in “First Reformed”), to name just a few—is also a reflection of his expansive empathy. “Acting, at its best, is like music,” he said. “You have to get inside your character’s song.”

Throughout his career, Hawke has consistently challenged himself to grow. He has appeared in more than eighty movies, predominantly independent films interspersed with Hollywood money-makers. He has directed four films, written three novels, and co-founded a theatre company. In the process, Hawke has been nominated for four Academy Awards (including two for Best Adapted Screenplay) and a Tony, for his performance, in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy “The Coast of Utopia,” as Mikhail Bakunin, the revolutionary Russian anarchist, whose bowwow personality resurfaces in the fulminations of Hawke’s John Brown. The range of Hawke’s roles—a romantic charmer (in the “Before” trilogy), a drug-addled Chet Baker (in “Born to Be Blue”), a guilt-ridden suicidal priest (in “First Reformed”), to name just a few—is also a reflection of his expansive empathy. “Acting, at its best, is like music,” he said. “You have to get inside your character’s song.”

more here.

Friday Poem

The Light Above the Grass

I wake up in the morning

And think

People are alive

Making things, children

And apps, they

Are running to one

Another and then my arm

Falls asleep.

Most of the men

Who did not exactly know

They were my father

Are dead

And so

My father keeps

dissolving.

Tonight

Both my sons are sleeping

At their mom’s apartment.

I can’t always feel

My legs

But I don’t want to tell

Anyone. I’m so afraid

Of everything.

Supreme Court: Would Trump pick inevitably mean a sharp right turn?

Henry Gass in The Christian Science Monitor:

With a presidential election less than five weeks away, and a new term at the U.S. Supreme Court just over a week away, President Donald Trump says he will, in a matter of days, announce his third nominee to the high court. The funeral for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose seat he would be filling after she died last week, is not scheduled until next week, but President Trump and other Republican Party leaders have made clear their intent to return the court to its full complement of nine justices as soon as possible. The announcement is certain to provoke a fierce and partisan confirmation battle in the U.S. Senate. But if the nomination is successful, it could transform the high court in a way perhaps not seen in close to a century, securing a two-thirds majority of conservative jurists that could advance conservative causes like regulating abortion, expanding gun rights, and reining in federal regulations at a speed and scope of its choosing.

With a presidential election less than five weeks away, and a new term at the U.S. Supreme Court just over a week away, President Donald Trump says he will, in a matter of days, announce his third nominee to the high court. The funeral for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose seat he would be filling after she died last week, is not scheduled until next week, but President Trump and other Republican Party leaders have made clear their intent to return the court to its full complement of nine justices as soon as possible. The announcement is certain to provoke a fierce and partisan confirmation battle in the U.S. Senate. But if the nomination is successful, it could transform the high court in a way perhaps not seen in close to a century, securing a two-thirds majority of conservative jurists that could advance conservative causes like regulating abortion, expanding gun rights, and reining in federal regulations at a speed and scope of its choosing.

To date, President Trump’s two other appointments – Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh – have replaced other members of the court’s right wing. But replacing Justice Ginsburg, for decades a liberal stalwart of the court, would represent a much starker rightward turn. It would likely see influence shift between the justices – namely away from Chief Justice John Roberts, who would cease to be the court’s ideological center. The conservative justices do not see eye to eye on every issue, a dynamic that could moderate decisions they reach in some areas of the law. But for the most part, it could be this reinforced conservative majority that would be shaping U.S. law for the next 15 or 20 years. The only questions would be how radically, and how quickly, the court moves.

More here.

The Fungal Evangelist Who Would Save the Bees

Merlin Sheldrake in Nautilus:

If anyone knows about going fungal, it’s Paul Stamets. I have often wondered whether he has been infected with a fungus that fills him with mycological zeal—and an irrepressible urge to persuade humans that fungi are keen to partner with us in new and peculiar ways. I went to visit him at his home on the west coast of Canada. The house is balanced on a granite bluff, looking out to sea. The roof is suspended on beams that look like mushroom gills. A Star Trek fan since the age of 12, Stamets christened his new house Starship Agarikon—agarikon is another name for Laricifomes officinalis, a medicinal wood-rotting fungus that grows in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

If anyone knows about going fungal, it’s Paul Stamets. I have often wondered whether he has been infected with a fungus that fills him with mycological zeal—and an irrepressible urge to persuade humans that fungi are keen to partner with us in new and peculiar ways. I went to visit him at his home on the west coast of Canada. The house is balanced on a granite bluff, looking out to sea. The roof is suspended on beams that look like mushroom gills. A Star Trek fan since the age of 12, Stamets christened his new house Starship Agarikon—agarikon is another name for Laricifomes officinalis, a medicinal wood-rotting fungus that grows in the forests of the Pacific Northwest.

…In Stamets’ world, fungal solutions run amok. Give him an insoluble problem and he’ll toss you a new way it can be decomposed, poisoned, or healed by a fungus. Fungi are veteran survivors of ecological disruption. Their ability to cling on—and often flourish—through periods of catastrophic change is one of their defining characteristics. They are inventive, flexible, and collaborative. With much of life on Earth threatened by human activity, are there ways we can partner with fungi to help us adapt? Stamets and a growing number of mycologists think exactly this. Many symbioses have formed in times of crisis. The algal partner in a lichen can’t make a living on bare rock without striking up a relationship with a fungus. Might it be that we can’t adjust to life on a damaged planet without cultivating new fungal relationships?

More here.

Thursday, September 24, 2020

Qian Zhongzhu Should Win the Nobel

Brendan O’Kane in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Qian Zhongshu is a tough pitch to win the Nobel prize in literature this year. He’s dead, for starters – traditionally an obstacle to many things, including winning Nobel prizes – and his total creative output consists solely of a few essays, several short stories, and a single novel. On the other hand, that novel, Fortress Besieged, seems to me to be the high-water mark of something significant, if hard to explain, so I’m going to make my best case for it being enough to secure Qian’s place in history. The book takes its title from a French proverb, sets its action in the China of the 1930s, and tracks the misfortunes of Fang Hongjian, a feckless, cowardly student returning from Europe with a mail-order doctorate in Chinese from an American university that exists only in the imagination of a crooked Irishman. It may be one of the most cosmopolitan books ever written; certainly it is, as literary critic C. T. Hsia said, one of the greatest Chinese novels of the 20th century.

More here.

How To Know When You Can Trust A COVID-19 Vaccine

Maggie Koerth in Five Thirty-Eight:

If a COVID-19 vaccine went on the market before Election Day, Kamala Harris said she’s not sure she’d take it. And she’s not alone. In a recent poll, a majority of Americans — 62 percent — said they were worried that the Trump administration would pressure the Food and Drug Administration to release a vaccine before it’s ready, and 54 percent said they simply wouldn’t take that hypothetical vaccine at all, even if it were free.

If a COVID-19 vaccine went on the market before Election Day, Kamala Harris said she’s not sure she’d take it. And she’s not alone. In a recent poll, a majority of Americans — 62 percent — said they were worried that the Trump administration would pressure the Food and Drug Administration to release a vaccine before it’s ready, and 54 percent said they simply wouldn’t take that hypothetical vaccine at all, even if it were free.

Scientists around the world are currently undertaking one of the fastest vaccine-development programs in history, trying to get the novel coronavirus under control as quickly as humanly possible. But the vaccines being tested sit at a nexus of misinformation and mistrust. Between Trump’s apparent meddling in federal health agencies’ decision-making, skepticism about the seriousness of the disease, and long-standing culture wars around the safety of vaccines in general, it’s easy to find yourself floundering, unsure who you can trust.

So I spoke with a handful of people who really know how vaccines, clinical trials and COVID-19 work to find out how to know when it’s a good idea to get the vaccine. They offered these four pieces of advice.

More here.

An interview with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin on the climate crisis, COVID-19, and the future of environmental politics

Noam Chomsky, Robert Pollin, and C. J. Polychroniou in the Boston Review:

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

Noam Chomsky: At the time of writing, concern for the COVID-19 crisis is virtually all-consuming. That’s understandable. It is severe and is severely disrupting lives. But it will pass, though at horrendous cost, and there will be recovery. There will not be recovery from the melting of the arctic ice sheets and the other consequences of global warming.

Not everyone is ignoring the advancing existential crisis. The sociopaths dedicated to accelerating the disaster continue to pursue their efforts, relentlessly. As before, Trump and his courtiers take pride in leading the race to destruction. As the United States was becoming the epicenter of the pandemic, thanks in no small measure to their folly, the White House cabal released its budget proposals. As expected, the proposals call for even deeper cuts in healthcare support and environmental protection, instead favoring the bloated military and the building of Trump’s Great Wall. And to add an extra touch of sadism, “the budget promotes a fossil fuel ‘energy boom’ in the United States, including an increase in the production of natural gas and crude oil.”

More here.

Barry Schwartz: What role does luck play in your life?

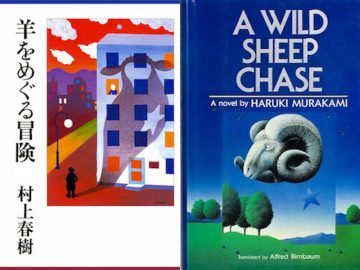

When Murakami Came to the States

David Karashima in The Paris Review:

On May 10, 1989, Haruki Murakami’s editor at Kodansha International, Elmer Luke, sent Murakami a fax reporting on the sale of U.S. paperback rights to A Wild Sheep Chase (to Plume for fifty-five thousand dollars) and asking him to take part in the promotional activities that were scheduled in New York that fall. Murakami declined. Several months later, Luke and Murakami met in person for the first time in Tokyo (together with another editor from KI), and on August 14, just three days before a copy of A Wild Sheep Chase arrived at the Murakamis’ home, Luke again asked Murakami to join him in New York. Murakami once again declined. On September 24, Luke asked again, saying that Murakami’s translator Alfred Birnbaum had become unable to attend, and that they had also managed to arrange an interview with the New York Times. Murakami finally relented.

On May 10, 1989, Haruki Murakami’s editor at Kodansha International, Elmer Luke, sent Murakami a fax reporting on the sale of U.S. paperback rights to A Wild Sheep Chase (to Plume for fifty-five thousand dollars) and asking him to take part in the promotional activities that were scheduled in New York that fall. Murakami declined. Several months later, Luke and Murakami met in person for the first time in Tokyo (together with another editor from KI), and on August 14, just three days before a copy of A Wild Sheep Chase arrived at the Murakamis’ home, Luke again asked Murakami to join him in New York. Murakami once again declined. On September 24, Luke asked again, saying that Murakami’s translator Alfred Birnbaum had become unable to attend, and that they had also managed to arrange an interview with the New York Times. Murakami finally relented.

Murakami and his wife, Yoko, landed in New York on October 21, and Luke and Tetsu Shirai, the head of Kodansha’s New York offices, picked them up at the airport. Shirai remembers handing Murakami a copy of that day’s New York Times folded open to a story in the arts section about him and A Wild Sheep Chase. The headline, “Young and Slangy Mix of the U.S. and Japan,” was followed by a tagline: “A best-selling novelist makes his American debut with a quest story.” “Of course, it was something that had been in the works,” Shirai tells me, “but I was surprised by how well the timing worked out.”

Shirai and Luke had chosen a hotel on the Upper East Side, thinking Murakami, an avid runner, would like to be near Central Park. Ten years later, Murakami would write in an essay for the women’s magazine an an that, while he preferred the Village and SoHo with its many bookshops and secondhand record stores, he ends up staying uptown in New York because “the appeal of running in Central Park in the morning is too great.”

More here.

Jacqueline du Pré – Dvořák Cello Concerto

The Gentle Genius of Mervyn Peake

Daisy Dunn at The Spectator:

To be a good illustrator, said Mervyn Peake, it is necessary to do two things. The first is to subordinate yourself entirely to the book. The second is ‘to slide into another man’s soul’.

To be a good illustrator, said Mervyn Peake, it is necessary to do two things. The first is to subordinate yourself entirely to the book. The second is ‘to slide into another man’s soul’.

In 1933, at the age of 22, Peake did precisely that. Relinquishing his studies at the Royal Academy Schools to move to Sark, in the Channel Islands, he co-founded an artists’ colony and took to sketching fishermen and romantic, ripple-lapped coves. He put a gold hoop in his right ear, a red-lined cape over his shoulders, and grew his hair long, like Israel Hands or Long John Silver.

The incredible thing was that he had yet to receive his commission to illustrate Treasure Island. By the time the job came through, in the late 1940s, he had been sliding into more piratical souls for more than 20 years.

more here.

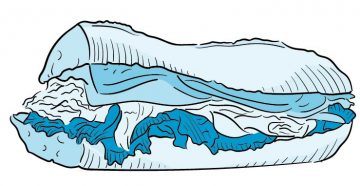

How to Make a Bodega Sandwich

Zain Khalid at The Believer:

To properly construct a bodega sandwich, sammich, hoagie, or sub, it is helpful to first consider Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. Forget for a second that this painting ushered in the dawn of Romanticism. Instead, study the shipwrecked subjects, the fifteen men with faces longer than hymns who endured their own appetites for thirteen days at sea.

To properly construct a bodega sandwich, sammich, hoagie, or sub, it is helpful to first consider Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. Forget for a second that this painting ushered in the dawn of Romanticism. Instead, study the shipwrecked subjects, the fifteen men with faces longer than hymns who endured their own appetites for thirteen days at sea.

Bodegas often serve those who can’t or won’t eat elsewhere. Bodegas are cheap, accept EBT cards, and employ polyglot cashiers who can translate a purposeful nod into a chopped cheese. Where else to go after a longer-than-expected trip across an ocean? Where else can the impossibly hungry go? Think about all this while selecting a bread. When in doubt, choose the plain hero. It should be between one and three days old.

more here.

The Election That Could Break America

Barton Gellman in The Atlantic:

The danger is not merely that the 2020 election will bring discord. Those who fear something worse take turbulence and controversy for granted. The coronavirus pandemic, a reckless incumbent, a deluge of mail-in ballots, a vandalized Postal Service, a resurgent effort to suppress votes, and a trainload of lawsuits are bearing down on the nation’s creaky electoral machinery.

The danger is not merely that the 2020 election will bring discord. Those who fear something worse take turbulence and controversy for granted. The coronavirus pandemic, a reckless incumbent, a deluge of mail-in ballots, a vandalized Postal Service, a resurgent effort to suppress votes, and a trainload of lawsuits are bearing down on the nation’s creaky electoral machinery.

…Let us not hedge about one thing. Donald Trump may win or lose, but he will never concede. Not under any circumstance. Not during the Interregnum and not afterward. If compelled in the end to vacate his office, Trump will insist from exile, as long as he draws breath, that the contest was rigged. Trump’s invincible commitment to this stance will be the most important fact about the coming Interregnum. It will deform the proceedings from beginning to end. We have not experienced anything like it before.

…Conventional commentary has trouble facing this issue squarely. Journalists and opinion makers feel obliged to add disclaimers when asking “what if” Trump loses and refuses to concede. “The scenarios all seem far-fetched,” Politico wrote, quoting a source who compared them to science fiction. Former U.S. Attorney Barbara McQuade, writing in The Atlantic in February, could not bring herself to treat the risk as real: “That a president would defy the results of an election has long been unthinkable; it is now, if not an actual possibility, at the very least something Trump’s supporters joke about.” But Trump’s supporters aren’t the only people who think extraconstitutional thoughts aloud. Trump has been asked directly, during both this campaign and the last, whether he will respect the election results. He left his options brazenly open. “What I’m saying is that I will tell you at the time. I’ll keep you in suspense. Okay?”

More here. (Note: Thanks to Mohsin Hamid)

Thursday Poem

“Maybe the greatest miracle is memory” – Brian Doyle

Father Joe

The holiest moments

were those curse words

Father Joe muttered under

his breath when some asshole

walked down the aisle or when, shit,

the choir started in too early. I always

volunteered to sit on his right so I could

hold the Bible open leaned in against my

sternum, Jesus Christ, as he read the Liturgy of the Word.

He’d gently, damnit, slide the long tassels across the pages

like a blessing. I still follow his eyes as he reads, arms

bent up from his elbows tucked into his side, palms up

Glory Be to the Highest, sonofabitch, listening

for those curse words in that sacred syntax.

by Michael Garrigan

from The Echotheo Review

Wednesday, September 23, 2020

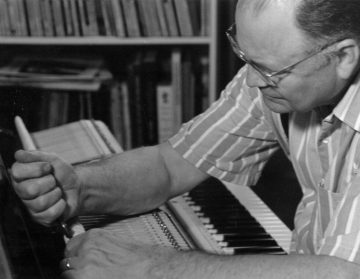

Verne Edquist (1931-2020) – Glenn Gould’s Piano Man

Katie Hafner at the website of the Glenn Gould Foundation:

Verne Edquist, a master piano tuner who spent most of his professional life working for one client – Glenn Gould – died peacefully on August 27 after a long illness. He was 89.

Verne Edquist, a master piano tuner who spent most of his professional life working for one client – Glenn Gould – died peacefully on August 27 after a long illness. He was 89.

I first met Verne in the summer of 2004, when I traveled to Toronto to start research for a book about Gould’s beloved CD-318. Verne and his wife, Lillian, welcomed me into their house on the outskirts of town and we sat for several hours in their living room, my recording device whirring away, while Verne recounted his life, and his work with the very eccentric Glenn Gould.

It was the start of an acquaintanceship that endured well past the publication of my book, A Romance on Three Legs: Glenn Gould’s Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Piano.

During that first meeting, I heard about the late-night recording sessions. Verne always arrived early to start tuning. Even after he finished tuning, he was required to stay throughout the session, in the event that a note should slip out of tune. I also heard about Gould’s endearingly bizarre coffee orders, his despair over the damaged CD-318, and his desperate calls to Verne late in his life, while re-recording The Goldberg Variations on a Yamaha.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Netta Engelhardt on Black Hole Information, Wormholes, and Quantum Gravity

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Stephen Hawking made a number of memorable contributions to physics, but perhaps his greatest was a puzzle: what happens to information that falls into a black hole? The question sits squarely at the overlap of quantum mechanics and gravitation, an area in which direct experimental input is hard to come by, so a great number of leading theoretical physicists have been thinking about it for decades. Now there is a possibility that physicists might have made some progress, by showing how subtle effects relate the radiation leaving a black hole to what’s going on inside. Netta Engelhardt is one of the contributors to these recent advances, and together we go through the black hole information puzzle, why wormholes might be important to the story, and what it all might teach us about quantum gravity.

Stephen Hawking made a number of memorable contributions to physics, but perhaps his greatest was a puzzle: what happens to information that falls into a black hole? The question sits squarely at the overlap of quantum mechanics and gravitation, an area in which direct experimental input is hard to come by, so a great number of leading theoretical physicists have been thinking about it for decades. Now there is a possibility that physicists might have made some progress, by showing how subtle effects relate the radiation leaving a black hole to what’s going on inside. Netta Engelhardt is one of the contributors to these recent advances, and together we go through the black hole information puzzle, why wormholes might be important to the story, and what it all might teach us about quantum gravity.

More here.

This Soldier’s Witness to the Iraq War Lie

Frederic Wehrey in the New York Review of Books:

A few weeks before I deployed to Iraq as a young US military officer, in the spring of 2003, my French-born father implored me to watch The Battle of Algiers, Gillo Pontecorvo’s dramatic reenactment of the 1950s Algerian insurgency against French colonial rule. There are many political and aesthetic reasons to see this masterpiece of cinéma vérité, not least of which is its portrayal of the Algerian capital’s evocative old city, or Casbah. One winter morning in 2014, more than a decade after I first saw the film, I took a stroll down the Casbah’s rain-washed alleys and into the newer French-built city. Scenes from the black-and-white movie—like the landmark Milk Bar café where a female Algerian guerrilla sets off a bomb that kills French civilians—jumped to life. The ensuing French military response, memorably depicted in the film, included arbitrary arrests, torture, and “false flag” bombings that only inflamed the Algerian insurrection.

It was these moral perils of counterinsurgency that my father hinted at. “Keep your eyes open,” he told me. This was a prescient warning, one that served as the backdrop for my deployment, even if the Algerian analogy was imperfect and would become overused. As American soldiers soon faced a guerrilla and civil war in Iraq for which they were woefully ill-equipped, intellectually and militarily, The Battle of Algiers would be screened and discussed at the Pentagon. To this day, it is taught to West Point cadets as a cautionary tale.

More here.