Category: Recommended Reading

The Martyrdom of Soleimani in the Propaganda Art of Iran

Amir Ahmadi Arian in the New York Review of Books:

One spring morning, on a return visit to Iran in 2015, I was sitting in a taxi stuck in traffic in Tehran’s Towhid Square and scanning the image-plastered dashboard to kill time. I took in the familiar snapshots: Los Angeles singers like Dariush and Ebi, scantily clad Bollywood actresses, framed verses from Qur’an swinging underneath the rear mirror, and an amulet dangling from its little frame. But amid this collage, there was also a photo of someone I had never seen before: a severe but distinguished-looking uniformed man. I pointed to the picture, and spoke.

“Do you like Soleimani?” I asked the taxi driver.

“Oh, of course,” he said. “He’s my man.” Then, seeing the confusion on my face, he added, “I hate mullahs as much as anyone, believe me. But Hajj Qassem is different.”

It was after that encounter that I began to notice how ubiquitous the image of Soleimani, a man whose name few people had known just a few years earlier, had become. In the windows of corner stores, on top of car trunks and van doors—posters of him were everywhere. Just like my cab driver, ordinary people had begun to revere him despite his steadfast loyalty to the system so many of them despised.

More here.

Clement Greenberg on Pollock with T J Clark

Women Philosophers of Seventeenth-Century England

David Cunning at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159).

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159).

more here.

Pissarro and Cézanne

T.J. Clark at the LRB:

Nonetheless, Cézanne came to Pissarro to unlearn his first style, and, seemingly, to change his mind about Courbet, Manet and Delacroix; or at least about what might be made from them, from their attitudes (their subjects, their stances) and their materials. Provocation in art would give way to patience, to exposure to optical events. The word ‘humble’ which Cézanne chose years later to characterise Pissarro – ‘humble and colossal’, he called him, and perhaps even ‘justified in his anarchist theories’ – sums up a number of things. The way forward for French painting, Cézanne seems to have decided in 1873, was to be found in the style that Monet had built, and to which Pissarro had given his distinctive stamp, in the very years when Cézanne had built his massive contrary to Monet’s lightness and impersonality. (‘Monet, around 1869, he struck the great blow’ was Cézanne’s verdict in retrospect. ‘Monet and Pissarro, the two great masters, the only two.’) The Courbet, Manet and Delacroix in oneself, in other words – and no doubt the three remained heroes – would have to be painted out. Sometime in the winter of 1872-73 (I shall return to this later) Cézanne borrowed a landscape Pissarro had done two years before, in the first heyday of Impressionism, and sat down to copy it stroke by stroke.

Nonetheless, Cézanne came to Pissarro to unlearn his first style, and, seemingly, to change his mind about Courbet, Manet and Delacroix; or at least about what might be made from them, from their attitudes (their subjects, their stances) and their materials. Provocation in art would give way to patience, to exposure to optical events. The word ‘humble’ which Cézanne chose years later to characterise Pissarro – ‘humble and colossal’, he called him, and perhaps even ‘justified in his anarchist theories’ – sums up a number of things. The way forward for French painting, Cézanne seems to have decided in 1873, was to be found in the style that Monet had built, and to which Pissarro had given his distinctive stamp, in the very years when Cézanne had built his massive contrary to Monet’s lightness and impersonality. (‘Monet, around 1869, he struck the great blow’ was Cézanne’s verdict in retrospect. ‘Monet and Pissarro, the two great masters, the only two.’) The Courbet, Manet and Delacroix in oneself, in other words – and no doubt the three remained heroes – would have to be painted out. Sometime in the winter of 1872-73 (I shall return to this later) Cézanne borrowed a landscape Pissarro had done two years before, in the first heyday of Impressionism, and sat down to copy it stroke by stroke.

more here.

The History of ‘Stolen’ Supreme Court Seats

Erick Trickey in Smithsonian:

A Supreme Court justice was dead, and the president, in his last year in office, quickly nominated a prominent lawyer to replace him. But the unlucky nominee’s bid was forestalled by the U.S. Senate, blocked due to the hostile politics of the time. It was 1852, but the doomed confirmation battle sounds a lot like 2016. “The nomination of Edward A. Bradford…as successor to Justice McKinley was postponed,” reported the New York Times on September 3, 1852. “This is equivalent to a rejection, contingent upon the result of the pending Presidential election. It is intended to reserve this vacancy to be supplied by Gen. Pierce, provided he be elected.”

A Supreme Court justice was dead, and the president, in his last year in office, quickly nominated a prominent lawyer to replace him. But the unlucky nominee’s bid was forestalled by the U.S. Senate, blocked due to the hostile politics of the time. It was 1852, but the doomed confirmation battle sounds a lot like 2016. “The nomination of Edward A. Bradford…as successor to Justice McKinley was postponed,” reported the New York Times on September 3, 1852. “This is equivalent to a rejection, contingent upon the result of the pending Presidential election. It is intended to reserve this vacancy to be supplied by Gen. Pierce, provided he be elected.”

Last year, when Senate Republicans refused to vote on anyone President Barack Obama nominated to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia, Democrats protested that the GOP was stealing the seat, flouting more than a century of Senate precedent about how to treat Supreme Court nominees. Senate Democrats such as Chuck Schumer and Patrick Leahy called the GOP’s move unprecedented, but wisely stuck to 20th-century examples when they talked about justices confirmed in election years. That’s because conservatives who argued that the Senate has refused to vote on Supreme Court nominees before had some history, albeit very old history, on their side.

What the Senate did to Merrick Garland in 2016, it did it to three other presidents’ nominees between 1844 and 1866, though the timelines and circumstances differed. Those decades of gridlock, crisis and meltdown in American politics left a trail of snubbed Supreme Court wannabes in their wake. And they produced justices who—as Neil Gorsuch might—ascended to Supreme Court seats set aside for them through political calculation.

More here.

The President Tests Positive for the Coronavirus, and a Nation Anticipates Chaos

David Remnick in The New Yorker:

President Donald Trump and his wife, Melania, have tested positive for the coronavirus, an announcement which is bound to throw the Presidential race into a state of grave uncertainty, if not chaos. The novel coronavirus pandemic has killed more than two hundred thousand Americans and more than a million people worldwide. On Friday morning, at 12:54 a.m. Eastern time, Trump tweeted, “Tonight, @FLOTUS and I tested positive for covid-19. We will begin our quarantine and recovery process immediately. We will get through this together!”

President Donald Trump and his wife, Melania, have tested positive for the coronavirus, an announcement which is bound to throw the Presidential race into a state of grave uncertainty, if not chaos. The novel coronavirus pandemic has killed more than two hundred thousand Americans and more than a million people worldwide. On Friday morning, at 12:54 a.m. Eastern time, Trump tweeted, “Tonight, @FLOTUS and I tested positive for covid-19. We will begin our quarantine and recovery process immediately. We will get through this together!”

Trump’s physician, Sean Conley, issued a statement saying that Trump and the First Lady were both “well at this time.” Trump had reportedly been hoarse during the day on Thursday, but his circle ascribed that to the rigors of rallies and other public events. “Rest assured I expect the President to continue carrying out his duties without disruption while recovering,” Conley wrote, “and I will keep you updated on any future developments.”

From the very beginning of the pandemic, Trump has denied or diminished the seriousness of covid-19, from its initial outbreak in China to its spread to Europe and beyond. In interviews with Bob Woodward, for the journalist’s book “Rage,” Trump admitted that he well understood from advisers how lethal and fast-spreading the disease could be, but in public statements he downplayed the danger, saying repeatedly that the virus would disappear with the summer’s warm weather and that there was little to worry about. To the despair of the scientific and medical communities, which have uniformly said that the disease can be best contained if people wear protective masks and maintain a social distance, Trump has repeatedly flouted their advice and touted disreputable treatments. As recently as Tuesday’s Presidential debate, in Cleveland, Trump mocked his opponent, Joe Biden, for wearing masks and practicing social distancing. “I don’t wear masks like him,” Trump said sarcastically of Biden, at the debate. “Every time you see him, he’s got a mask. He could be speaking two hundred feet away from him, and he shows up with the biggest mask I’ve ever seen.”

More here.

Friday Poem

A Man in His Life

A man in his life has no time to have

Time for everything.

He has no room to have room

For every desire. Ecclesiastes was wrong to claim that.

A man has to hate and love all at once,

With the same eyes to cry and to laugh

With the same hands to throw stones

And to gather them,

Make love in war and war in love.

And hate and forgive and remember and forget

And order and confuse and eat and digest

What long history does

In so many years.

A man in his life has no time.

When he loses he seeks

When he finds he forgets

When he forgets he loves

When he loves he begins forgetting.

And his soul is knowing

And very professional,

Only his body remains an amateur

Always. It tries and fumbles.

He doesn’t learn and gets confused,

Drunk and blind in his pleasures and pains.

In autumn, he will die like a fig,

Shriveled, sweet, full of himself.

The leaves dry out on the ground,

And the naked branches point

To the place where there is time for everything.

by Yehuda Amichai

from the collection, The Selected Poetry Of Yehuda Amichai (Literature of the Middle East)

University of California Press.

Thursday, October 1, 2020

The Writer–Translator Equation

Tim Parks in the New York Review of Books:

The translator is a writer. The writer is a translator. How many times have I run up against these assertions?—in a chat between translators protesting because they are not listed in a publisher’s index of authors; or in the work of literary theorists, even poets (“Each text is unique, yet at the same time it is the translation of another text,” observed Octavio Paz). Others claim that because language is referential, any written text is a translation of the world referred to.

The translator is a writer. The writer is a translator. How many times have I run up against these assertions?—in a chat between translators protesting because they are not listed in a publisher’s index of authors; or in the work of literary theorists, even poets (“Each text is unique, yet at the same time it is the translation of another text,” observed Octavio Paz). Others claim that because language is referential, any written text is a translation of the world referred to.

In recent months, I have been dividing my working day between writing in the morning and translating in the afternoon. Maybe comparing the two activities would be a good way to test this writer–translator equation.

I’m writing a novel. It began to present itself as a possibility perhaps a year before I started work on it. Two vague ideas that had been bumping around for a while came together and took on a little form. One: an older man, once prominent in cultural circles, has withdrawn from all contact with his peers and stopped following news or media in any form; he lives as a kind of urban hermit, an acute observer but, as it were, uninformed. Two: someone receives, out of the blue, an invitation to attend the funeral, in a foreign country, of an extremely distinguished colleague, friend, and rival of many years ago.

More here.

This Overlooked Variable Is the Key to the Pandemic

Zeynep Tufekci in The Atlantic:

There’s something strange about this coronavirus pandemic. Even after months of extensive research by the global scientific community, many questions remain open.

There’s something strange about this coronavirus pandemic. Even after months of extensive research by the global scientific community, many questions remain open.

Why, for instance, was there such an enormous death toll in northern Italy, but not the rest of the country? Just three contiguous regions in northern Italy have 25,000 of the country’s nearly 36,000 total deaths; just one region, Lombardy, has about 17,000 deaths. Almost all of these were concentrated in the first few months of the outbreak. What happened in Quito, Ecuador, in April, when so many thousands died so quickly that bodies were abandoned in the sidewalks and streets? Why, in the spring of 2020, did so few cities account for a substantial portion of global deaths, while many others with similar density, weather, age distribution, and travel patterns were spared? What can we really learn from Sweden, hailed as a great success by some because of its low case counts and deaths as the rest of Europe experiences a second wave, and as a big failure by others because it did not lock down and suffered excessive death rates earlier in the pandemic? Why did widespread predictions of catastrophe in Japan not bear out? The baffling examples go on.

I’ve heard many explanations for these widely differing trajectories over the past nine months—weather, elderly populations, vitamin D, prior immunity, herd immunity—but none of them explains the timing or the scale of these drastic variations. But there is a potential, overlooked way of understanding this pandemic that would help answer these questions, reshuffle many of the current heated arguments, and, crucially, help us get the spread of COVID-19 under control.

More here.

A feature-length documentary about America’s system of public lands and the fight to protect them

Working people are forever kept on the brink of going broke

Kevin P. Donovan in the Boston Review:

E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class relates the story of a Manchester silk weaver who, in 1835, complained of being subjugated to the urgent demands of the market. This skilled artisan observed how capitalists determined the pace at which they worked, while workers faced externally imposed timelines. “Labour,” the weaver lamented, “is always carried to market by those who have nothing else to keep or to sell, and who, therefore, must part with it immediately.” Rejecting any comparison of workers and capitalists, he stated, “if I, in an imitation of the capitalist” refused to sell what I have “because an inadequate price is offered me for it, can I bottle it? Can I lay it up in salt?” No, he bitterly answered, “labour cannot by any possibility be stored, but must be every instant sold or every instant lost.”

E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class relates the story of a Manchester silk weaver who, in 1835, complained of being subjugated to the urgent demands of the market. This skilled artisan observed how capitalists determined the pace at which they worked, while workers faced externally imposed timelines. “Labour,” the weaver lamented, “is always carried to market by those who have nothing else to keep or to sell, and who, therefore, must part with it immediately.” Rejecting any comparison of workers and capitalists, he stated, “if I, in an imitation of the capitalist” refused to sell what I have “because an inadequate price is offered me for it, can I bottle it? Can I lay it up in salt?” No, he bitterly answered, “labour cannot by any possibility be stored, but must be every instant sold or every instant lost.”

It did not take Marx’s later dictum that workers are free in a “double sense”—to work or to starve—to explain the distinction between income and wealth to the silk weaver. Wealth is an asset, providing a buffer against unexpected shocks in the short term and economic security in the long run. On the other hand, labor (the means to one’s income) expires as soon as it stops. There is no way to store labor—to “bottle it” or “lay it up in salt”—thus working people navigate a series of urgent demands on their time and well-being.

More here.

The Three Books of Occult Philosophy

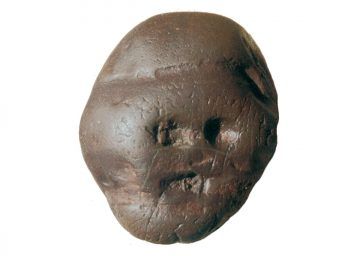

Chance in Art

Dario Gamboni at Cabinet Magazine:

“Chance in art” can mean many different things, so numerous and so varied that one may be tempted to dismiss the term as a misnomer or a lexical straw man, like so many adherents to the notion of divine or natural causality have done in the past: “Chance seems to be only a term, by which we express our ignorance of the cause of any thing.”1 But there may be a plane on which at least some of these meanings and forms meet and which can illuminate them—this essay will attempt to locate it.

“Chance in art” can mean many different things, so numerous and so varied that one may be tempted to dismiss the term as a misnomer or a lexical straw man, like so many adherents to the notion of divine or natural causality have done in the past: “Chance seems to be only a term, by which we express our ignorance of the cause of any thing.”1 But there may be a plane on which at least some of these meanings and forms meet and which can illuminate them—this essay will attempt to locate it.

One classical interpretation of “chance in art” is that of the “image made by chance.”2 The phenomenon is documented across times and cultures and can be understood as a particularly explicit manifestation of the active, cognitive (or “projective”) nature of visual perception. In fact, the earliest known “image” associated with humans—or rather pre-humans—, the pebble found at Makapansgat in South Africa, is supposed to have been selected, transported, and preserved some three million years ago because it happened to look like a face.

more here.

A Modernist Jigsaw in 110 Pieces

Michael Hofmann at The Paris Review:

Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist.

Wolfgang Koeppen’s novel Pigeons on the Grass, first published in 1951 as Tauben im Gras, is among the earliest, grandest, and most poetically satisfying reckonings in fiction with the postwar state of the world. What have we done to ourselves? What may we hope for? Is life from now on going to be different? Is it even going to be possible? These are the unasked and unanswerable questions that hover around this great novel composed in bite-size chunks, a cross section of a damaged society presented—natch!—in cutup. I once described it as a “Modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces,” but it is as compulsively readable as Dickens or Elmore Leonard. The form catches the eye, but the content is no slouch either. It must be one of the shortest of the universal books, the ones of which you think, If it isn’t in here, it doesn’t exist.

more here.

Thursday Poem

Rome and Nature

Rome has fallen, ye see it lying

Heaped in undistinguished ruin:

Nature is alone undying.

by Percy Bysshe Shelly

Proud Boys are a dangerous ‘white supremacist’ group say US agencies

Jason Wilson in The Guardian:

The far-right Proud Boys group whom Donald Trump told to “stand by” during this week’s presidential debate is seen as a dangerous organization by law enforcement, according to leaked assessments of the organization from federal, state and local agencies. Trump’s refusal to condemn white supremacists during the debate, and his suggestion that the Proud Boys “stand by” during the current 2020 election campaign sent shockwaves through American politics. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls the Proud Boys a hate group. Files from the Blueleaks trove of leaked law enforcement documents reveal warnings that the Proud Boys, who some of the US agencies label as “white supremacists” and “extremists”, and others as a “gang”, show persistent concerns about the group’s menace to minority groups and even police officers, and its dissemination of dangerous conspiracy theories.

The far-right Proud Boys group whom Donald Trump told to “stand by” during this week’s presidential debate is seen as a dangerous organization by law enforcement, according to leaked assessments of the organization from federal, state and local agencies. Trump’s refusal to condemn white supremacists during the debate, and his suggestion that the Proud Boys “stand by” during the current 2020 election campaign sent shockwaves through American politics. The Southern Poverty Law Center calls the Proud Boys a hate group. Files from the Blueleaks trove of leaked law enforcement documents reveal warnings that the Proud Boys, who some of the US agencies label as “white supremacists” and “extremists”, and others as a “gang”, show persistent concerns about the group’s menace to minority groups and even police officers, and its dissemination of dangerous conspiracy theories.

In a 22-page 2019 document titled Violent Extremism in Colorado: a Reference Guide for Law Enforcement, published by CIAC, the state’s Division of Homeland Security, and the Colorado Department of Public Safety, various incidents of violence involving the Proud Boys are discussed under the heading of White Supremacist Extremism. On page 15 of the document, the group is discussed in terms of the “threat to Colorado” from white supremacist extremists, and the “concern that white supremacist extremists will continue attacking members of the community who threaten their belief of Caucasian superiority”.

More here.

“This Is So Unpresidential”: Notes from the Worst Debate in American History

Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

What does the worst debate in American history look like? It looks like the debate that took place on Tuesday night between President Donald Trump and the former Vice-President Joe Biden. It was a joke, a mess, a disaster. A “shit show,” a “dumpster fire,” a national humiliation. No matter how bad you thought the debate would be, it was worse. Way worse. Trump shouted, he bullied, he hectored, he lied, and he interrupted, over and over again.

What does the worst debate in American history look like? It looks like the debate that took place on Tuesday night between President Donald Trump and the former Vice-President Joe Biden. It was a joke, a mess, a disaster. A “shit show,” a “dumpster fire,” a national humiliation. No matter how bad you thought the debate would be, it was worse. Way worse. Trump shouted, he bullied, he hectored, he lied, and he interrupted, over and over again.

Remarkably enough, it was seemingly on purpose. Losing in the polls, and with the country stricken by a pandemic that has claimed two hundred thousand American lives, the President offered incoherent bluster, inflammatory racism, and personal attacks on his opponent’s son. But mostly what came through was Trump’s refusal to shut up. He talked and talked and talked. He talked over Biden. He talked over the moderator, Fox News’ Chris Wallace. He talked over Biden some more. How bad was it? The line that history is likely to record as among the most memorable was Biden’s lament, at the end of the debate’s very first segment: “Will you just shut up, man? This is so unpresidential.”

More here.

Wednesday, September 30, 2020

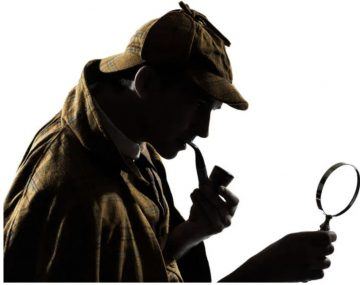

Sherlock Holmes and the Curious Case of Several Million Chinese Fans

Paul French in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

China’s long love affair with England’s greatest consulting detective is a mystery worth solving. The BBC hit show Sherlock, which ran from 2010-17, proved a smash with Chinese viewers: 4.72 million viewers watched one episode, eager to find out how Holmes dodged death after plunging off the roof of London’s St. Bart’s Hospital at the end of the previous season. Weibo, China’s Twitter, was filled with chatter about the show by fans of “Curly Fu” and “Peanut” (the nicknames given by Chinese fans to Holmes and Watson, because they sound like the Chinese pronunciation of their names).

China’s long love affair with England’s greatest consulting detective is a mystery worth solving. The BBC hit show Sherlock, which ran from 2010-17, proved a smash with Chinese viewers: 4.72 million viewers watched one episode, eager to find out how Holmes dodged death after plunging off the roof of London’s St. Bart’s Hospital at the end of the previous season. Weibo, China’s Twitter, was filled with chatter about the show by fans of “Curly Fu” and “Peanut” (the nicknames given by Chinese fans to Holmes and Watson, because they sound like the Chinese pronunciation of their names).

The often lumbering behemoth of the BBC indeed showed itself rather fleet of foot in China. Faced with The Case of the Pirate DVD Seller and the Mystery of the Illegal Download Site, Auntie Beeb performed a shrewd deduction of its own by licensing Sherlock (with official Chinese subtitles) to Youku, a Chinese video streaming site, which screened it just hours after its British air time. (Had they waited even a few hours more, they knew, the illegal downloads and bootleg DVDs would have hit the streets.) But why not make it available in China at the same time it airs in Britain? Unlike a good detective mystery, China’s TV bosses don’t like surprise endings: the censors have to check for any anti-China content.

More here.

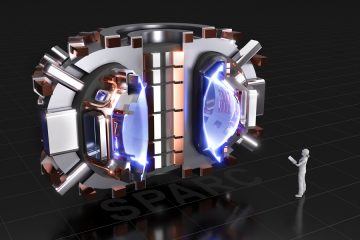

Validating the physics behind the new MIT-designed fusion experiment

David L. Chandler in MIT News:

Two and a half years ago, MIT entered into a research agreement with startup company Commonwealth Fusion Systems to develop a next-generation fusion research experiment, called SPARC, as a precursor to a practical, emissions-free power plant.

Two and a half years ago, MIT entered into a research agreement with startup company Commonwealth Fusion Systems to develop a next-generation fusion research experiment, called SPARC, as a precursor to a practical, emissions-free power plant.

Now, after many months of intensive research and engineering work, the researchers charged with defining and refining the physics behind the ambitious tokamak design have published a series of papers summarizing the progress they have made and outlining the key research questions SPARC will enable.

Overall, says Martin Greenwald, deputy director of MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center and one of the project’s lead scientists, the work is progressing smoothly and on track. This series of papers provides a high level of confidence in the plasma physics and the performance predictions for SPARC, he says. No unexpected impediments or surprises have shown up, and the remaining challenges appear to be manageable. This sets a solid basis for the device’s operation once constructed, according to Greenwald.

More here.