Sasha Geffen at Artforum:

A new compilation, Transmissions: The Music of Beverly Glenn-Copeland, traces the artist’s career from his early days as a folk balladeer to his omnivorous current practice. Its narrative mirrors that of Posy Dixon’s 2019 documentary, Keyboard Fantasies: The Beverly Glenn-Copeland Story, which explores the years he spent working in obscurity, the realization of his identity as a transgender man in his fifties, and how in his seventies he came to be embraced by millennial listeners. The film captures part of a performance at Le Guess Who? in Utrecht, a full recording of which was released as a live album earlier this year. Dixon’s camera glides across the faces of a mostly young audience beaming at Glenn-Copeland and his band, composed of musicians in their twenties. This same crowd appears on Transmissions during “Deep River,” an exuberant live rendition of a well-known spiritual. Glenn-Copeland invites the audience to sing along with the song’s climax, and they do—tentatively at first, and then with gusto. When the band stops, he thanks the audience emphatically, an illustrative moment of genuine intergenerational interaction wisely included in the compilation.

A new compilation, Transmissions: The Music of Beverly Glenn-Copeland, traces the artist’s career from his early days as a folk balladeer to his omnivorous current practice. Its narrative mirrors that of Posy Dixon’s 2019 documentary, Keyboard Fantasies: The Beverly Glenn-Copeland Story, which explores the years he spent working in obscurity, the realization of his identity as a transgender man in his fifties, and how in his seventies he came to be embraced by millennial listeners. The film captures part of a performance at Le Guess Who? in Utrecht, a full recording of which was released as a live album earlier this year. Dixon’s camera glides across the faces of a mostly young audience beaming at Glenn-Copeland and his band, composed of musicians in their twenties. This same crowd appears on Transmissions during “Deep River,” an exuberant live rendition of a well-known spiritual. Glenn-Copeland invites the audience to sing along with the song’s climax, and they do—tentatively at first, and then with gusto. When the band stops, he thanks the audience emphatically, an illustrative moment of genuine intergenerational interaction wisely included in the compilation.

more here.

Because Gornick is foremost a memoirist, any tour of her work must contend with her autobiography as she tells it, in fragments. There is no single book in which she narrates her life story straight through; “truth in memoir,” she writes in The Situation and the Story (2001), “is achieved not through a recital of actual events.” Instead, each of her books marshals different pieces of her life in service of a central insight, whether she’s writing memoir, criticism, reportage, or a biography of someone else. She is dedicated to nonfiction as a genre, but has a novelist’s instinct for selection. To recount her biography chronologically thus requires some reconstruction.

Because Gornick is foremost a memoirist, any tour of her work must contend with her autobiography as she tells it, in fragments. There is no single book in which she narrates her life story straight through; “truth in memoir,” she writes in The Situation and the Story (2001), “is achieved not through a recital of actual events.” Instead, each of her books marshals different pieces of her life in service of a central insight, whether she’s writing memoir, criticism, reportage, or a biography of someone else. She is dedicated to nonfiction as a genre, but has a novelist’s instinct for selection. To recount her biography chronologically thus requires some reconstruction. The immediate aftermath of the

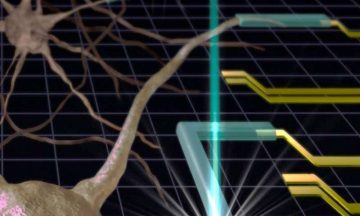

The immediate aftermath of the  Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have developed a new method of 3-D-printing gels and other soft materials. Published in a new paper, it has the potential to create complex structures with nanometer-scale precision. Because many gels are compatible with living cells, the new method could jump-start the production of soft tiny medical devices such as drug delivery systems or flexible electrodes that can be inserted into the human body.

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have developed a new method of 3-D-printing gels and other soft materials. Published in a new paper, it has the potential to create complex structures with nanometer-scale precision. Because many gels are compatible with living cells, the new method could jump-start the production of soft tiny medical devices such as drug delivery systems or flexible electrodes that can be inserted into the human body. What does coffee do to you? Dinah Lenney’s Coffee is a free-form exploration of such surprisingly complicated questions: Why do we drink coffee? What gives it its power? Humans have been considering these and other coffee-related queries (like “Is it good for my health?” and “Is it good for my society?”) for centuries, ever since they first encountered the substance. Lenney is most interested in coffee’s direct effects on our lived experience, and what they mean.

What does coffee do to you? Dinah Lenney’s Coffee is a free-form exploration of such surprisingly complicated questions: Why do we drink coffee? What gives it its power? Humans have been considering these and other coffee-related queries (like “Is it good for my health?” and “Is it good for my society?”) for centuries, ever since they first encountered the substance. Lenney is most interested in coffee’s direct effects on our lived experience, and what they mean. It

It  I recall an illuminating moment a decade or so ago. Cathy Guisewite had just announced she would step back from creating new instalments of her long-running

I recall an illuminating moment a decade or so ago. Cathy Guisewite had just announced she would step back from creating new instalments of her long-running  ON MY DOORMAT,

ON MY DOORMAT, When I was a teenager I was, like most teenagers, preoccupied with the idea that somewhere on the horizon there was a Now. The present moment came to a peak out there; it achieved a continuous apotheosis of nowness, a wave endlessly breaking on an invisible shore. I wasn’t quite sure what specific form this climax took, but it had to involve some concatenation of records, poems, pictures, parties, and behavior. Out there all of those items would be somehow made manifest: the pictures walking along in the middle of the street, the right song broadcast in the air every minute, the parties behaving like the poems and vice versa. Since it was 1967 when I became a teenager, I suspected that the Now would stir together rock ’n’ roll bands and mod girls and cigarettes and bearded poets and sunglasses and Italian movie stars and pointy shoes and spies. But there had to be much more than that, things I could barely guess. The present would be occurring in New York and Paris and London and California while I lay in my narrow bed in New Jersey, which was a swamplike clot of the dead recent past.

When I was a teenager I was, like most teenagers, preoccupied with the idea that somewhere on the horizon there was a Now. The present moment came to a peak out there; it achieved a continuous apotheosis of nowness, a wave endlessly breaking on an invisible shore. I wasn’t quite sure what specific form this climax took, but it had to involve some concatenation of records, poems, pictures, parties, and behavior. Out there all of those items would be somehow made manifest: the pictures walking along in the middle of the street, the right song broadcast in the air every minute, the parties behaving like the poems and vice versa. Since it was 1967 when I became a teenager, I suspected that the Now would stir together rock ’n’ roll bands and mod girls and cigarettes and bearded poets and sunglasses and Italian movie stars and pointy shoes and spies. But there had to be much more than that, things I could barely guess. The present would be occurring in New York and Paris and London and California while I lay in my narrow bed in New Jersey, which was a swamplike clot of the dead recent past. The smart play for Trump is to postpone the nomination to reduce the risk of Democratic mobilization, and to warn Republicans of the risks should he lose. Trump’s people do not usually execute the smart play. They are often the victims of the hyper-ideological media they consume, which deceive them about what actually is the smart play. This time, though, they may just be desperate enough to break long-standing pattern and try something different.

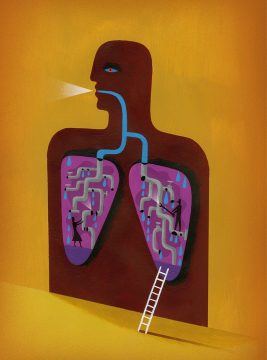

The smart play for Trump is to postpone the nomination to reduce the risk of Democratic mobilization, and to warn Republicans of the risks should he lose. Trump’s people do not usually execute the smart play. They are often the victims of the hyper-ideological media they consume, which deceive them about what actually is the smart play. This time, though, they may just be desperate enough to break long-standing pattern and try something different. Over the course of two decades spent developing treatments for the genetic lung disease cystic fibrosis, biologist Fredrick Van Goor has had hundreds of conversations with patients. But he remembers one in particular. The discussion was about the genetics of cystic fibrosis, a disease that develops when a person inherits two faulty copies of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. This gene encodes the CFTR protein, which resides in the cell membrane and transports chloride and bicarbonate ions out of the cell. More than 2,000 variants of CFTR have been identified, and more than 350 of them are known to produce enough disruption in the protein’s function to trigger the debilitating and life-shortening condition. The focus of the conversation was the inevitable inequities of personalized medicine, which can be highly effective for people who meet certain criteria, but will leave others behind — as was the case for this patient. “He described it as being on a sinking ship, when all of the other lifeboats have left,” Van Goor recalls. “That image has stuck with me.”

Over the course of two decades spent developing treatments for the genetic lung disease cystic fibrosis, biologist Fredrick Van Goor has had hundreds of conversations with patients. But he remembers one in particular. The discussion was about the genetics of cystic fibrosis, a disease that develops when a person inherits two faulty copies of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. This gene encodes the CFTR protein, which resides in the cell membrane and transports chloride and bicarbonate ions out of the cell. More than 2,000 variants of CFTR have been identified, and more than 350 of them are known to produce enough disruption in the protein’s function to trigger the debilitating and life-shortening condition. The focus of the conversation was the inevitable inequities of personalized medicine, which can be highly effective for people who meet certain criteria, but will leave others behind — as was the case for this patient. “He described it as being on a sinking ship, when all of the other lifeboats have left,” Van Goor recalls. “That image has stuck with me.” “Prisons are created internally / and are found everywhere.” My conversations with Spoon Jackson keep returning to this point, a line from one of his poems. Prisons are both real and imaginary. All people experience some kind of prison, some to a greater degree than others. Those degrees are not coincidental. Jackson, a 63-year-old Black man, has been serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole for 42 years and has lived in a series of prisons. He discovered poetry one day, about 30 years ago, sitting in his cell, looking over the bay at San Quentin. At least that’s how he tells it.

“Prisons are created internally / and are found everywhere.” My conversations with Spoon Jackson keep returning to this point, a line from one of his poems. Prisons are both real and imaginary. All people experience some kind of prison, some to a greater degree than others. Those degrees are not coincidental. Jackson, a 63-year-old Black man, has been serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole for 42 years and has lived in a series of prisons. He discovered poetry one day, about 30 years ago, sitting in his cell, looking over the bay at San Quentin. At least that’s how he tells it. There are as many as 9 million feral swine across the U.S., their populations having expanded from about 17 states to 38 over the last three decades. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but Ryan Brook, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who researches wild pigs, predicts that they will occupy 386,000 square miles across the country by the end of 2020, and they’re currently expanding at about 35,000 square miles a year.

There are as many as 9 million feral swine across the U.S., their populations having expanded from about 17 states to 38 over the last three decades. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but Ryan Brook, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who researches wild pigs, predicts that they will occupy 386,000 square miles across the country by the end of 2020, and they’re currently expanding at about 35,000 square miles a year.