Bethany Augliere in Nautilus:

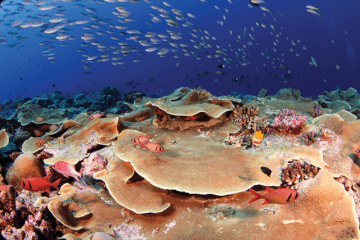

Today, news of damaged or devastated coral reefs has become commonplace. Reefs face many threats, including bleaching, disease, overfishing, pollution and even invasive species. While the fates of the reefs may seem almost universally bleak, some scientists think the future of these vital marine ecosystems could be more complicated—and perhaps even hopeful. Ecologist Stuart Sandin, director of the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif., studies how and why reefs change over time and how best to manage them in light of looming threats. To understand clearly what’s happening in the oceans, Sandin and his team travel to remote islands around the world, take thousands of images of local reefs, and then stitch them together into three-dimensional photomosaics. They’ve been using this method for seven years, and to their surprise, what they’ve found is not all doom-and-gloom. In fact, they have observed coral reefs rebounding and growing as soon as two years after massive bleaching events.

Today, news of damaged or devastated coral reefs has become commonplace. Reefs face many threats, including bleaching, disease, overfishing, pollution and even invasive species. While the fates of the reefs may seem almost universally bleak, some scientists think the future of these vital marine ecosystems could be more complicated—and perhaps even hopeful. Ecologist Stuart Sandin, director of the Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif., studies how and why reefs change over time and how best to manage them in light of looming threats. To understand clearly what’s happening in the oceans, Sandin and his team travel to remote islands around the world, take thousands of images of local reefs, and then stitch them together into three-dimensional photomosaics. They’ve been using this method for seven years, and to their surprise, what they’ve found is not all doom-and-gloom. In fact, they have observed coral reefs rebounding and growing as soon as two years after massive bleaching events.

…For instance, one of the reefs the team is studying is off the Micronesian island of Kiritimati, also known as Christmas Island, in the Republic of Kiribati about 240 kilometers north of the equator. Kiritimati is the world’s largest coral atoll. During the 2015–2016 El Niño event, the area experienced sea-surface temperatures 1.5 to 3 degrees Celsius higher than normal for 10 months, according to data reported by climatologist Kim Cobb of Georgia Tech and colleagues in 2016. As of November 2015, 50 to 90 percent of Kiritimati’s corals were bleached, and 30 percent were dead. But when the 100IC team went to Kiritimati in 2018, they saw new corals growing. “We didn’t expect to go to some of these remote places that experienced utter death and destruction, and see [corals] come back,” Zgliczynski says. They also saw healthy coralline algae—algae that produce a hard skeleton—which help cement reefs and provide habitat for juvenile coral to grow. “The reef got hit hard and the corals do not look like they did five years ago, but we’re starting to see life come back,” he says.

More here.