William Dalrymple in The Spectator:

India’s golden age as the centre of the Indophilic Sanskrit cosmopolis lasted an entire millennium. From 1200 onwards, however, it was India’s fate to be drawn into a second transregional world. The first Islamic conquests of India happened in the 11th century, with the capture of Lahore in 1021. Persianised Turks, from what is now central Afghanistan, seized Delhi from its Hindu rulers in 1192. By 1323, they had established a sultanate as far south as Madurai, towards the tip of the peninsula, and other sultanates were founded all the way from Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east.

India’s golden age as the centre of the Indophilic Sanskrit cosmopolis lasted an entire millennium. From 1200 onwards, however, it was India’s fate to be drawn into a second transregional world. The first Islamic conquests of India happened in the 11th century, with the capture of Lahore in 1021. Persianised Turks, from what is now central Afghanistan, seized Delhi from its Hindu rulers in 1192. By 1323, they had established a sultanate as far south as Madurai, towards the tip of the peninsula, and other sultanates were founded all the way from Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east.

Today, the 13th-century conquests of the Persianate Delhi sultans are usually perceived as having been made by ‘Muslims’, but medieval Sanskrit inscriptions don’t identify India’s Central Asian invaders by that term. Instead, the newcomers are identified by linguistic and ethnic affiliation, most typically as Turushka — Turks — or as ‘the lords of the horses’, which suggests that they were not seen primarily in terms of their religious identity. And although the conquests were initially marked by carnage and by the mass destruction of Hindu and Buddhist temples and places of learning, India quickly transformed the new arrivals.

Within a few centuries, a hybrid Persianate, Indo-Islamic civilisation emerged out of the meeting of these two worlds. As Richard M. Eaton writes at the beginning of his remarkable new book India in the Persianate Age 1000–1765.

More here.

The world might be a different place if American Presidents had not been felled by disease or hidden debilitating conditions. In February, 1945, just two months before his death, President

The world might be a different place if American Presidents had not been felled by disease or hidden debilitating conditions. In February, 1945, just two months before his death, President  Most scientists say that Earth-life probably did originate on Earth. The standard thinking goes that somehow the conditions were ideal for just the right minerals to come together in a series of chemical reactions that yielded self-replicating molecules, that is, early life. But the particulars of that scenario have been tricky to pin down, leaving room for other possibilities. The concept of panspermia was kicked off, in part, by the humongous eruption of a volcano on the island of Krakatoa in 1883, says Dr. Melosh. The eruption completely sterilized the island, but just months later, life began to flourish anew. Naturalists explained that the miraculous regeneration came from seeds and insects floating on the winds or the tides from nearby islands, and that got some scientists thinking about the cosmos. Perhaps early Earth was like a barren island, too, they speculated, and the seeds of life or life itself drifted around space and alighted on our planet at just the right moment.

Most scientists say that Earth-life probably did originate on Earth. The standard thinking goes that somehow the conditions were ideal for just the right minerals to come together in a series of chemical reactions that yielded self-replicating molecules, that is, early life. But the particulars of that scenario have been tricky to pin down, leaving room for other possibilities. The concept of panspermia was kicked off, in part, by the humongous eruption of a volcano on the island of Krakatoa in 1883, says Dr. Melosh. The eruption completely sterilized the island, but just months later, life began to flourish anew. Naturalists explained that the miraculous regeneration came from seeds and insects floating on the winds or the tides from nearby islands, and that got some scientists thinking about the cosmos. Perhaps early Earth was like a barren island, too, they speculated, and the seeds of life or life itself drifted around space and alighted on our planet at just the right moment. How our experience in the theatre during one of his plays relates to our lives outside is a question that has nagged at discussions of Stoppard’s standing as a writer. His kind of quantum dramatics messes with our minds and our understanding of time and we love it, but when we get home we still have to set the alarm for work the next day. Does this mean that his plays are little more than a diverting display of verbal fireworks, clever but of no significance, or are deeper themes about our experience of life being addressed? At the very least, his work reveals a constant endeavour to decipher the puzzles of existence. As Hannah, a character in one of his best-loved plays,

How our experience in the theatre during one of his plays relates to our lives outside is a question that has nagged at discussions of Stoppard’s standing as a writer. His kind of quantum dramatics messes with our minds and our understanding of time and we love it, but when we get home we still have to set the alarm for work the next day. Does this mean that his plays are little more than a diverting display of verbal fireworks, clever but of no significance, or are deeper themes about our experience of life being addressed? At the very least, his work reveals a constant endeavour to decipher the puzzles of existence. As Hannah, a character in one of his best-loved plays,  Thirty years ago, the philosopher Judith Butler*, now 64, published a book that revolutionised popular attitudes on gender.

Thirty years ago, the philosopher Judith Butler*, now 64, published a book that revolutionised popular attitudes on gender.  In 1938, Alma Fielding, a 34-year-old housewife from the south London suburb of Thornton Heath, apparently became possessed by a violent spirit. It started one evening when Alma was in bed afflicted by kidney pain while her builder husband, Les, was suffering from tooth problems next to her. After seeing a six-finger handprint appear on the mirror, the couple were attacked by a flying eiderdown, felt a dank wind blowing and saw a glass spontaneously shatter. In the weeks and months that followed, the Fieldings, their teenage son, Don, and their lodger, George, were terrorised by what seemed wildly malevolent paranormal forces. Sunday Pictorial reporters sent to investigate were met with flying eggs, teacups breaking in midair and a brass fender thumping down a staircase.

In 1938, Alma Fielding, a 34-year-old housewife from the south London suburb of Thornton Heath, apparently became possessed by a violent spirit. It started one evening when Alma was in bed afflicted by kidney pain while her builder husband, Les, was suffering from tooth problems next to her. After seeing a six-finger handprint appear on the mirror, the couple were attacked by a flying eiderdown, felt a dank wind blowing and saw a glass spontaneously shatter. In the weeks and months that followed, the Fieldings, their teenage son, Don, and their lodger, George, were terrorised by what seemed wildly malevolent paranormal forces. Sunday Pictorial reporters sent to investigate were met with flying eggs, teacups breaking in midair and a brass fender thumping down a staircase. Jackson T. Reinhardt in Inquiries Journal:

Jackson T. Reinhardt in Inquiries Journal:

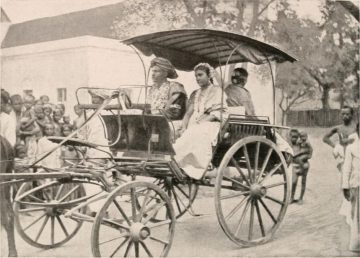

Shuvatri Dasgupta over at the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas:

Shuvatri Dasgupta over at the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas: Branko Milanovic in Global Policy:

Branko Milanovic in Global Policy: A veil of solemnity descends upon the land at times like this, when elected officials or public figures get sick or die. We wish them speedy recovery, or extend sympathies, as we should. We ignore their faults and failings, as we would want our own ignored. These are the norms of politics and public life. Established norms, like behaving with dignity and self-restraint in a presidential debate, or condemning racist terrorists and murderers. For the record, we should all wish Donald and Melania Trump a full and speedy recovery. But that does not answer the fundamental question this president will leave behind when he leaves office. What norms survive a man who takes pleasure in destroying norms?

A veil of solemnity descends upon the land at times like this, when elected officials or public figures get sick or die. We wish them speedy recovery, or extend sympathies, as we should. We ignore their faults and failings, as we would want our own ignored. These are the norms of politics and public life. Established norms, like behaving with dignity and self-restraint in a presidential debate, or condemning racist terrorists and murderers. For the record, we should all wish Donald and Melania Trump a full and speedy recovery. But that does not answer the fundamental question this president will leave behind when he leaves office. What norms survive a man who takes pleasure in destroying norms? Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),

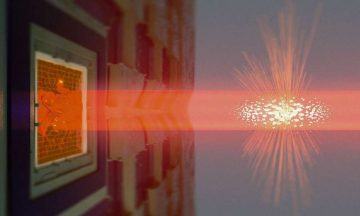

Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),  A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.