Paul Vallely in The Guardian:

Philanthropy, it is popularly supposed, transfers money from the rich to the poor. This is not the case. In the US, which statistics show to be the most philanthropic of nations, barely a fifth of the money donated by big givers goes to the poor. A lot goes to the arts, sports teams and other cultural pursuits, and half goes to education and healthcare. At first glance that seems to fit the popular profile of “giving to good causes”. But dig down a little.

Philanthropy, it is popularly supposed, transfers money from the rich to the poor. This is not the case. In the US, which statistics show to be the most philanthropic of nations, barely a fifth of the money donated by big givers goes to the poor. A lot goes to the arts, sports teams and other cultural pursuits, and half goes to education and healthcare. At first glance that seems to fit the popular profile of “giving to good causes”. But dig down a little.

The biggest donations in education in 2019 went to the elite universities and schools that the rich themselves had attended. In the UK, in the 10-year period to 2017, more than two-thirds of all millionaire donations – £4.79bn – went to higher education, and half of these went to just two universities: Oxford and Cambridge. When the rich and the middle classes give to schools, they give more to those attended by their own children than to those of the poor. British millionaires in that same decade gave £1.04bn to the arts, and just £222m to alleviating poverty.

The common assumption that philanthropy automatically results in a redistribution of money is wrong. A lot of elite philanthropy is about elite causes. Rather than making the world a better place, it largely reinforces the world as it is. Philanthropy very often favours the rich – and no one holds philanthropists to account for it.

More here.

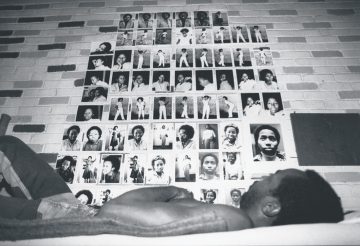

WE CAN ALL AGREE NOW that American prisons are a malignant feature of contemporary life, broadening inequalities, destroying families, worsening racial disparities, and facilitating widespread state-sanctioned premature death, to name just a few of the most obvious iniquities. But inside these prisons, people do find imaginative ways to survive. The institutional culture of incarceration has spawned individual and communal acts of inspired genius—acts credited entirely to people, and not to the prisons where they are forced to live—modalities of making and ways of surviving that involve types of creativity unique to communities held captive. To do time in prison is to become an expert at doing time in prison, to develop specific skills and levels of knowledge that can only be acquired heuristically rather than gleaned, learned, read about. Experientially, prison alters sensory life: sight—drab and reduced colors and textures; sound—loud and invasive; human touch—not part of the ideological plan for “rehabilitation”; taste—very little aside from salt; smell—at least here in California, the smell of prisons up and down the state derives from a single overpowering cleaning solution used in every facility of the entire massive system and called, I kid you not, Cell Block 64.

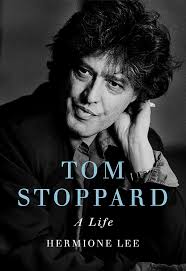

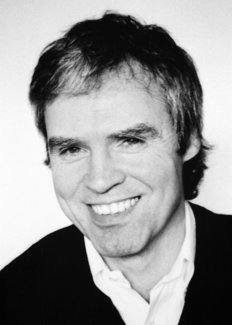

WE CAN ALL AGREE NOW that American prisons are a malignant feature of contemporary life, broadening inequalities, destroying families, worsening racial disparities, and facilitating widespread state-sanctioned premature death, to name just a few of the most obvious iniquities. But inside these prisons, people do find imaginative ways to survive. The institutional culture of incarceration has spawned individual and communal acts of inspired genius—acts credited entirely to people, and not to the prisons where they are forced to live—modalities of making and ways of surviving that involve types of creativity unique to communities held captive. To do time in prison is to become an expert at doing time in prison, to develop specific skills and levels of knowledge that can only be acquired heuristically rather than gleaned, learned, read about. Experientially, prison alters sensory life: sight—drab and reduced colors and textures; sound—loud and invasive; human touch—not part of the ideological plan for “rehabilitation”; taste—very little aside from salt; smell—at least here in California, the smell of prisons up and down the state derives from a single overpowering cleaning solution used in every facility of the entire massive system and called, I kid you not, Cell Block 64. Until I read Hermione Lee’s life of Tom Stoppard, I didn’t know it was possible to bask in envy. As if being handsome, funny and a dazzling writer (and good at cricket and fly-fishing) weren’t enough, Stoppard is immensely rich – not just in money but also, Lee shows, in family, lovers, friends and even, which may sound pompous, moral qualities. ‘What is the Good?’ Emily asks in his 2013 radio play Darkside. ‘It is nothing but a contest of kindness.’ We learn of his devotion to his mother, brother, sons and grandchildren, his ability to stay friends with his exes and his work on behalf of good causes, beneficiaries of which include the opposition in Belarus, which he has supported since before Lukashenko came to power, and refugees encamped at Calais. There are a couple of brilliant paragraphs late in the book about the meanings and pitfalls of charm, and also of luck. A small part of Stoppard’s good luck is that, unlike the subjects of most worthwhile biographies, he’s alive to enjoy this one.

Until I read Hermione Lee’s life of Tom Stoppard, I didn’t know it was possible to bask in envy. As if being handsome, funny and a dazzling writer (and good at cricket and fly-fishing) weren’t enough, Stoppard is immensely rich – not just in money but also, Lee shows, in family, lovers, friends and even, which may sound pompous, moral qualities. ‘What is the Good?’ Emily asks in his 2013 radio play Darkside. ‘It is nothing but a contest of kindness.’ We learn of his devotion to his mother, brother, sons and grandchildren, his ability to stay friends with his exes and his work on behalf of good causes, beneficiaries of which include the opposition in Belarus, which he has supported since before Lukashenko came to power, and refugees encamped at Calais. There are a couple of brilliant paragraphs late in the book about the meanings and pitfalls of charm, and also of luck. A small part of Stoppard’s good luck is that, unlike the subjects of most worthwhile biographies, he’s alive to enjoy this one. Pity the poor closed-caption writers. Pity the poor ASL interpreters. But most of all, pity poor us, the American electorate.

Pity the poor closed-caption writers. Pity the poor ASL interpreters. But most of all, pity poor us, the American electorate. Recorded history is five thousand years old. Modern science, which has been with us for just four centuries, has remade its trajectory. We are no smarter individually than our medieval ancestors, but we benefit, as a civilization, from antibiotics and electronics, vitamins and vaccines, synthetic materials and weather forecasts; we comprehend our place in the universe with an exactness that was once unimaginable. I’d found that science was two-faced: simultaneously thrilling and tedious, all-encompassing and narrow. And yet this was clearly an asset, not a flaw. Something about that combination had changed the world completely.

Recorded history is five thousand years old. Modern science, which has been with us for just four centuries, has remade its trajectory. We are no smarter individually than our medieval ancestors, but we benefit, as a civilization, from antibiotics and electronics, vitamins and vaccines, synthetic materials and weather forecasts; we comprehend our place in the universe with an exactness that was once unimaginable. I’d found that science was two-faced: simultaneously thrilling and tedious, all-encompassing and narrow. And yet this was clearly an asset, not a flaw. Something about that combination had changed the world completely. How can, and should, we talk to each other, especially to people with whom we disagree? “Free speech” is rightfully entrenched as an important value in liberal democratic societies, but implementing it consistently and fairly is a tricky business. Political theorist Teresa Bejan comes to this question from a philosophical and historical perspective, managing to relate broad principles to modern hot-button issues. We talk about the importance of tolerating disreputable beliefs, the senses in which speech acts can be harmful, and how “civility” places demands on listeners as well as speakers.

How can, and should, we talk to each other, especially to people with whom we disagree? “Free speech” is rightfully entrenched as an important value in liberal democratic societies, but implementing it consistently and fairly is a tricky business. Political theorist Teresa Bejan comes to this question from a philosophical and historical perspective, managing to relate broad principles to modern hot-button issues. We talk about the importance of tolerating disreputable beliefs, the senses in which speech acts can be harmful, and how “civility” places demands on listeners as well as speakers. Like many other liberals, I’m devastated by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, which opened the way for President Donald Trump to nominate a third Supreme Court justice in his first term. And I’m revolted by the hypocrisy of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s willingness to confirm Trump’s nominee after refusing to even allow a vote on Judge Merrick Garland.

Like many other liberals, I’m devastated by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, which opened the way for President Donald Trump to nominate a third Supreme Court justice in his first term. And I’m revolted by the hypocrisy of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s willingness to confirm Trump’s nominee after refusing to even allow a vote on Judge Merrick Garland.

Karachi is home. My bustling, chaotic city of about 20 million people on the Arabian Sea is an ethnically and religiously diverse metropolis and the commercial capital of Pakistan, generating more than half of the country’s revenue. Over the decades, Karachi has survived

Karachi is home. My bustling, chaotic city of about 20 million people on the Arabian Sea is an ethnically and religiously diverse metropolis and the commercial capital of Pakistan, generating more than half of the country’s revenue. Over the decades, Karachi has survived

It’s uncontroversial among biologists that many species have two, distinct biological sexes. They’re distinguished by the way that they package their DNA into ‘gametes’, the sex cells that merge to make a new organism. Males produce small gametes, and females produce large gametes. Male and female gametes are very different in structure, as well as in size. This is familiar from human sperm and eggs, and the same is true in worms, flies, fish, molluscs, trees, grasses and so forth.

It’s uncontroversial among biologists that many species have two, distinct biological sexes. They’re distinguished by the way that they package their DNA into ‘gametes’, the sex cells that merge to make a new organism. Males produce small gametes, and females produce large gametes. Male and female gametes are very different in structure, as well as in size. This is familiar from human sperm and eggs, and the same is true in worms, flies, fish, molluscs, trees, grasses and so forth. Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than

Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than

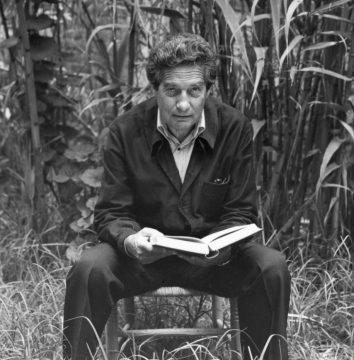

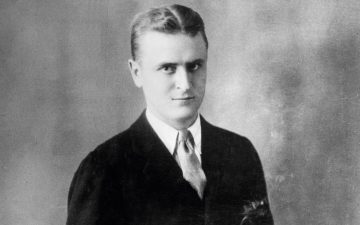

Maybe my book is rotten,” F Scott Fitzgerald told a friend, in February 1925, shortly before the publication of The Great Gatsby, “but I don’t think so”. If the first half of his sentence was perfunctory, the second half was the wildest kind of understatement. By that point, Fitzgerald knew what he had achieved. Six months earlier, he informed Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that his work in progress “is about the best American novel ever written”. And Perkins’s reaction had done little to shake his sense of confidence. He called the book “a wonder”, adding: “As for sheer writing, it’s astonishing.”

Maybe my book is rotten,” F Scott Fitzgerald told a friend, in February 1925, shortly before the publication of The Great Gatsby, “but I don’t think so”. If the first half of his sentence was perfunctory, the second half was the wildest kind of understatement. By that point, Fitzgerald knew what he had achieved. Six months earlier, he informed Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that his work in progress “is about the best American novel ever written”. And Perkins’s reaction had done little to shake his sense of confidence. He called the book “a wonder”, adding: “As for sheer writing, it’s astonishing.”