The World is a Beautiful Place

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind happiness

not always being

so very much fun

if you don’t mind a touch of hell

now and then

just when everything is fine

because even in heaven

they don’t sing

all the time

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind some people dying

all the time

or maybe only starving

some of the time

which isn’t half so bad

if it isn’t you

Oh the world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t much mind

a few dead minds

in the higher places

or a bomb or two

now and then

in your upturned faces

or such other improprieties

as our Name Brand society

is prey to

with its men of distinction

and its men of extinction

and its priests

and other patrolmen

and its various segregations

and congressional investigations

and other constipations

that our fool flesh

is heir to

Yes the world is the best place of all

for a lot of such things as

making the fun scene

and making the love scene

and making the sad scene

and singing low songs of having

inspirations

and walking around

looking at everything

and smelling flowers

and goosing statues

and even thinking

and kissing people and

making babies and wearing pants

and waving hats and

dancing

and going swimming in rivers

on picnics

in the middle of the summer

and just generally

‘living it up’

Yes

but then right in the middle of it

comes the smiling

mortician

by Lawrence Ferlinghetti

from A Coney Island of the Mind

New Directions Publishing

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cells change constantly. Researchers tend to study their dynamics in two ways. One method is to watch them live under a microscope, where a limited number of types of molecules can be tracked for days with fluorescent tags. Another way is in test tubes at a single time point, usually the end of an experiment, where mRNA molecules can be measured and compared with those in other cells

Cells change constantly. Researchers tend to study their dynamics in two ways. One method is to watch them live under a microscope, where a limited number of types of molecules can be tracked for days with fluorescent tags. Another way is in test tubes at a single time point, usually the end of an experiment, where mRNA molecules can be measured and compared with those in other cells  Who are you? What’s going on deep inside yourself? How do you understand your own mind? The ancient sages had big debates about this, and now modern neuroscience is helping us sort it all out. When my amateur fascination with neuroscience began, roughly two decades ago, the scientists seemed to spend a lot of time trying to figure out where in the brain different functions were happening. That led to a lot of simplistic shorthand in the popular conversation: Emotion is in the amygdala. Motivation is in the nucleus accumbens. Back in those days management consultants could make a good living by giving presentations with slides of brain scans while uttering sentences like: “You can see that the parietal lobe is all lit up. This proves that …”

Who are you? What’s going on deep inside yourself? How do you understand your own mind? The ancient sages had big debates about this, and now modern neuroscience is helping us sort it all out. When my amateur fascination with neuroscience began, roughly two decades ago, the scientists seemed to spend a lot of time trying to figure out where in the brain different functions were happening. That led to a lot of simplistic shorthand in the popular conversation: Emotion is in the amygdala. Motivation is in the nucleus accumbens. Back in those days management consultants could make a good living by giving presentations with slides of brain scans while uttering sentences like: “You can see that the parietal lobe is all lit up. This proves that …” A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird.

A few days after my brother died, I sat in the living room of a dead house and made eye contact with a bird. What we’re building today is not “an AI” that might cooperate or rebel, but an expanding capacity to design, develop, produce, deploy, and adapt complex systems at scale—the basis for a hypercapable world. Taking this prospect seriously changes what to expect and what we can do.

What we’re building today is not “an AI” that might cooperate or rebel, but an expanding capacity to design, develop, produce, deploy, and adapt complex systems at scale—the basis for a hypercapable world. Taking this prospect seriously changes what to expect and what we can do. When Katherine Dunn

When Katherine Dunn Unlike earlier protest waves, this unrest unfolds as Iran’s core pillars—its economic viability, coercive capacity, and external deterrence—fail simultaneously, creating a systemic crisis the regime has never faced and may not survive.

Unlike earlier protest waves, this unrest unfolds as Iran’s core pillars—its economic viability, coercive capacity, and external deterrence—fail simultaneously, creating a systemic crisis the regime has never faced and may not survive. What conditions did Brodkey observe? That already in 1992, “the old American middle class is gone,” its scattered remaining members defined only by participation in such institutions as the stock market, the tax system and “an interlocking web of universities.” Most of them live in isolated suburbs, which “do not and cannot do much to preserve culture or the interplay of groups and classes that heretofore made up American education in politics, in American political realities.” Due to the consequent loss of “political and social ballast,” awareness of local reality has given way to the seductiveness of mass fantasy. “Moral issues are complex and tangled. The jury system argues tacitly that all issues are arguable. And they are. And that time changes things. And it does. That adjudication and rights and duties are complex matters.” Common sense, but also “almost all culture, literature, history, philosophy, even religion, if studied and pondered, tell us that. The disappearance of common sense and the ebbing of culture and the advance of the dreamed-of and dreamlike are clear signs of social danger.”

What conditions did Brodkey observe? That already in 1992, “the old American middle class is gone,” its scattered remaining members defined only by participation in such institutions as the stock market, the tax system and “an interlocking web of universities.” Most of them live in isolated suburbs, which “do not and cannot do much to preserve culture or the interplay of groups and classes that heretofore made up American education in politics, in American political realities.” Due to the consequent loss of “political and social ballast,” awareness of local reality has given way to the seductiveness of mass fantasy. “Moral issues are complex and tangled. The jury system argues tacitly that all issues are arguable. And they are. And that time changes things. And it does. That adjudication and rights and duties are complex matters.” Common sense, but also “almost all culture, literature, history, philosophy, even religion, if studied and pondered, tell us that. The disappearance of common sense and the ebbing of culture and the advance of the dreamed-of and dreamlike are clear signs of social danger.” If you read a book

If you read a book In the early 1990s, a groundswell of young women raised on second-wave feminism but marginalized within the supposedly progressive realm of punk music rose up to make themselves heard, in a movement known as riot grrrl. Bands like

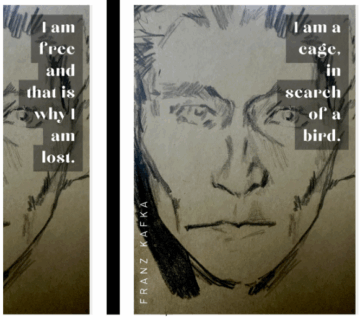

In the early 1990s, a groundswell of young women raised on second-wave feminism but marginalized within the supposedly progressive realm of punk music rose up to make themselves heard, in a movement known as riot grrrl. Bands like  Dr. Franz Kafka, as he is officially listed, is buried in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, about a mile down the road from where I live in the neighbourhood of Žižkov. The greater Olšany Cemetery, which it adjoins, is across the street from my apartment. I often go there for walks in the evening, meandering along its overgrown rows and flower-crowded graves. Kafka’s headstone looks like an expressionist prism, a long diamond slightly fattened at its top. The stone bed in front of it is frequently littered with candles, pens, scraps of paper, rocks painted with pictures of beetles. He is interred there along with his mother Julie and his father Hermann (whom he is unable to escape even in death). Max Brod, without whom we’d know nothing of Kafka, has a plaque on the opposite wall. Given that Kafka instructed Brod to burn all of his work “unread,” he almost certainly would not have welcomed people flocking to his grave, so whenever I stop by to say hello to him, I think to myself: “He would hate this.”

Dr. Franz Kafka, as he is officially listed, is buried in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery, about a mile down the road from where I live in the neighbourhood of Žižkov. The greater Olšany Cemetery, which it adjoins, is across the street from my apartment. I often go there for walks in the evening, meandering along its overgrown rows and flower-crowded graves. Kafka’s headstone looks like an expressionist prism, a long diamond slightly fattened at its top. The stone bed in front of it is frequently littered with candles, pens, scraps of paper, rocks painted with pictures of beetles. He is interred there along with his mother Julie and his father Hermann (whom he is unable to escape even in death). Max Brod, without whom we’d know nothing of Kafka, has a plaque on the opposite wall. Given that Kafka instructed Brod to burn all of his work “unread,” he almost certainly would not have welcomed people flocking to his grave, so whenever I stop by to say hello to him, I think to myself: “He would hate this.” T

T Jimmy Wales, an Internet entrepreneur from Huntsville, Alabama, now based in London, is best known for creating Wikipedia, which launched in January 2001. The online encyclopedia now holds more than seven million articles and has become a standard guide for anyone seeking information.

Jimmy Wales, an Internet entrepreneur from Huntsville, Alabama, now based in London, is best known for creating Wikipedia, which launched in January 2001. The online encyclopedia now holds more than seven million articles and has become a standard guide for anyone seeking information. Eisenman has said she started out in a “degenerate and proto-queer” environment, asserting that, when she arrived in New York in the late 1980s, there “was no such thing as queer yet.” The artist wasn’t interested in modernism’s pieties. She was after drama. Her influences include Caravaggio, Giotto, Michelangelo, Grant Wood, Georg Baselitz, and WPA murals, all mixed into clusterfucks of seriousness and stupidity, tenderness and the grotesquerie. Her Alice in Wonderland depicts a tiny Alice whose head is jammed into the vagina of Wonder Woman. She’s created scenes of castration and Betty Rubble and Wilma Flintstone in flagrante ecstasy. Artist Amy Sillman wrote that Eisenman renders figures “with riotous unpredictability, anti-Puritanically taking delight in misbehavior on every level.” Eisenman takes the sacred and drags it across the barroom floor.

Eisenman has said she started out in a “degenerate and proto-queer” environment, asserting that, when she arrived in New York in the late 1980s, there “was no such thing as queer yet.” The artist wasn’t interested in modernism’s pieties. She was after drama. Her influences include Caravaggio, Giotto, Michelangelo, Grant Wood, Georg Baselitz, and WPA murals, all mixed into clusterfucks of seriousness and stupidity, tenderness and the grotesquerie. Her Alice in Wonderland depicts a tiny Alice whose head is jammed into the vagina of Wonder Woman. She’s created scenes of castration and Betty Rubble and Wilma Flintstone in flagrante ecstasy. Artist Amy Sillman wrote that Eisenman renders figures “with riotous unpredictability, anti-Puritanically taking delight in misbehavior on every level.” Eisenman takes the sacred and drags it across the barroom floor. During a week in December when violence seemed to rap on every door, I saw two plays about women who take their lives into their own hands: Hedda Gabler at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, and Anna Christie at Saint Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The plays were written thirty years apart. Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in 1891, and Anna Christie by Eugene O’Neill in 1921. That year, Alexander Woollcott, reviewing the first production of Anna Christie for the New York Times, wrote, “All grown-up playgoers should jot down in their notebooks the name of Anna Christie as that of a play they really ought to see.” Though O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize for Anna Christie, the play has been infrequently performed. It is being directed now by Thomas Kail, and Anna is played by his wife, Michelle Williams. On the other hand, Hedda Gabler, directed this time by James Bundy and starring Marianna Gailus, is a warhorse.

During a week in December when violence seemed to rap on every door, I saw two plays about women who take their lives into their own hands: Hedda Gabler at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, and Anna Christie at Saint Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The plays were written thirty years apart. Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in 1891, and Anna Christie by Eugene O’Neill in 1921. That year, Alexander Woollcott, reviewing the first production of Anna Christie for the New York Times, wrote, “All grown-up playgoers should jot down in their notebooks the name of Anna Christie as that of a play they really ought to see.” Though O’Neill won the Pulitzer Prize for Anna Christie, the play has been infrequently performed. It is being directed now by Thomas Kail, and Anna is played by his wife, Michelle Williams. On the other hand, Hedda Gabler, directed this time by James Bundy and starring Marianna Gailus, is a warhorse.