Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

The “Satiric, Terrifying” Legacy Of Poet Weldon Kees

Dana Gioia at The Book Haven:

I first discovered the poetry of Weldon Kees in 1976—fifty years ago—while working a summer job in Minneapolis. I came across a selection of his poems in a library anthology. I didn’t recognize his name. I might have skipped over the section had I not noticed in the brief headnote that he had died in San Francisco by leaping off the Golden Gate Bridge. As a Californian in exile, I found that grim and isolated fact intriguing.

I first discovered the poetry of Weldon Kees in 1976—fifty years ago—while working a summer job in Minneapolis. I came across a selection of his poems in a library anthology. I didn’t recognize his name. I might have skipped over the section had I not noticed in the brief headnote that he had died in San Francisco by leaping off the Golden Gate Bridge. As a Californian in exile, I found that grim and isolated fact intriguing.

I decided to read a poem or two. Instead, I read them all, with growing excitement and wonder. I recognized that I was reading a major poet. He was a head-spinning cocktail of contradictions, simultaneously satiric and terrifying, intimate and enigmatic. He used traditional forms with an experimental sensibility. He depicted apocalyptic outcomes with mordant humor. I had found the poet I had been searching for. Why had I never heard of him? Embarrassed by my ignorance, I decided to read everything I could find by and about him.

It was a Saturday afternoon. I had the rest of the weekend free. I drove to the main branch of the Minneapolis Public Library, heady with anticipation.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

China leads research in 90% of crucial technologies — a dramatic shift this century

Xiaoying You in Nature:

The ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker evaluated high-quality research on 74 current and emerging technologies this year, up from the 64 technologies it analysed last year. China is ranked number one for research on 66 of the technologies, including nuclear energy, synthetic biology and small satellites, and the United States topped the remaining 8, including quantum computing and geoengineering.

The ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker evaluated high-quality research on 74 current and emerging technologies this year, up from the 64 technologies it analysed last year. China is ranked number one for research on 66 of the technologies, including nuclear energy, synthetic biology and small satellites, and the United States topped the remaining 8, including quantum computing and geoengineering.

The results reflect a drastic reversal. At the beginning of this century, the United States led more than 90% of the assessed technologies, whereas China led less than 5% of them, according to the 2024 edition of the tracker.

“China has made incredible progress on science and technology that is reflected in research and development, as well as in publications,” says Ilaria Mazzocco, who researches China’s industrial policy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a non-profit research organization based in Washington DC.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Frank Gehry: The Liberator

Martin Filler at the NYRB:

The great liberator of late-twentieth-century architecture, Gehry was a latter-day Alexander who sliced through the Gordian Knot formed by an exhausted Modernism intertwined with a callow Postmodernism. Instead of trying to untangle those two discordant stylistic visions, which wastefully dominated American architectural discourse during the 1970s and 1980s, he showed an exhilarating way forward with freeform designs that drew on advanced contemporary art as their primary source of inspiration. He made the world safe for oddball buildings, and whatever one might think of the idiosyncratic architecture by the generation who followed him—Santiago Calatrava, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Thom Mayne, and their ilk—their careers would be unthinkable without the precedent he set.

Although his dramatic departure from architectural convention was at first confrontational and forbidding, it gradually became more buoyant and embracing. As his clients’ budgets increased and he moved from corrugated metal to shiny titanium, unfinished plywood to polished Douglas fir, and rubber matting to travertine flooring, his architecture lost none of its expressive power and appealed to many who’d found his earlier tough-guy efforts more alienating than audacious.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Root Causes of Senseless Violence

Ivana Hughes in Common Dreams:

I write this from the front of a Columbia classroom in which about 60 first-year college students are taking the final exam for Frontiers of Science. Yes, it’s a Sunday, but the class is required of all Columbia College students and so having the exam on the weekend ensures that there won’t be conflicts with the exams for other courses they are taking. The 60 students in my classroom are a fraction of the nearly 740 taking the course this semester.

I write this from the front of a Columbia classroom in which about 60 first-year college students are taking the final exam for Frontiers of Science. Yes, it’s a Sunday, but the class is required of all Columbia College students and so having the exam on the weekend ensures that there won’t be conflicts with the exams for other courses they are taking. The 60 students in my classroom are a fraction of the nearly 740 taking the course this semester.

The exam began at 2 pm, less than 24 hours after the shooting at Brown University, and just hours after many of us learned about the shooting in Sydney, Australia. Given these devastating events, I offered this morning that anyone who was adversely affected could take the exam later in the week or take what at Columbia is called an incomplete, which means that they would take the final exam at the start of next semester and only then be assigned a grade. Only about two dozen students took this offer, some sharing personal stories about having close friends from childhood or high school among the victims at Brown. It makes sense that the high-achieving students that Columbia attracts would have high-achieving friends at Brown. Some also hail from Providence and have had impacted family members.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

You’re Probably Not Addicted to Social Media

Kristen French in Nautilus:

Social media can be tough to ignore these days. There is so much of it, and it’s so accessible, right there glowing on the phones in our pockets and purses. Many of us find ourselves scrolling through the feeds of friends, family, and so-called influencers more often than we might like (or like to admit).

Social media can be tough to ignore these days. There is so much of it, and it’s so accessible, right there glowing on the phones in our pockets and purses. Many of us find ourselves scrolling through the feeds of friends, family, and so-called influencers more often than we might like (or like to admit).

But does that mean we’re addicted in a clinical sense, or just indulging a bad habit?

The distinction matters, it turns out. While the United States Surgeon General warned in early 2023 that excessive use of social media can have neurological effects similar to substance abuse, for most people, the language of addiction is neither accurate nor helpful, according to a recent study by a pair of researchers from the California Institution of Technology and the University of California, Los Angeles. The findings were published in Scientific Reports.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, December 14, 2025

Donald McIntyre (1934 – 2025) Operatic Bass-Baritone

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Socialism After AI

Evgeny Morozov in The Ideas Letter:

Artificial intelligence has produced a rare kind of popular curiosity. Not only among investors and founders, but among people who open a browser, type a question, and feel—however inaccurately—that something on the other side is thinking with them. That phenomenology matters. Whatever we think about hype, hallucinations, or OpenAI’s capitalization table, AI arrives as a technology whose uses are discovered after deployment, whose boundaries are porous, and whose side‑effects appear in places nobody designed for. “Generative” is not just a marketing word; it names a genuine instability.

For socialists, this instability poses a specific challenge. And their reflexes are familiar: Regulate platforms, tax windfalls, nationalize leading firms, plug their models into a planning apparatus. But if socialism is to be more than capitalism with nicer dashboards—if it really is a project of collectively remaking material life, not just of redistributing its outputs—it has to answer a harder question: Can it offer a better way of living with this technology than capitalism does? Can it deliver a distinct form of life worth wanting rather than just a fairer share of what capital has already made?

Once you pose the problem like this, something embarrassing appears. For a tradition obsessed with maximizing productive forces, socialism has been remarkably quick to bracket some of them from politics. It treats technology as a neutral kit to be dropped into better institutions once these exist. Take railways, nuclear plants, or language models: If capitalism misuses them, socialism promises to finally aim them at the common good. The real question, however, is whether even the most ambitious recent socialist theory escapes this limitation—or whether it reproduces neutrality at a higher level of sophistication.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Can machines suffer?

Conor Purcelli in Aeon:

Across northern Europe and Canada during the 19th and 20th centuries, workers roamed coastlines and pack ice, beating infant seals to death with clubs. White ice was smeared red. Annual kill rates for seals are estimated in the hundreds of thousands, all done with the purpose of turning them into raw industrial materials for the production of clothing, oil, and meat. Even if their suffering was real, many considered it inconsequential. Seals, like many other creatures, were seen as little more than tools or resources.

However, views of animal suffering and pain soon shifted. In 1881, Henry Wood Elliott reported on the ‘wholesale destruction’ of seals in Alaska, leading to international outcry and the establishment of new treaties. And in ‘The White Seal’ (1893), Rudyard Kipling told a sympathetic story from the perspective of the hunted animals themselves. If someone killed a seal pup today, they would likely be charged in a court of law.

This widening of the so-called moral circle – the slow extension of empathy and rights beyond the boundaries we once took for granted – has changed many of our relationships with other species. It is why factory-farmed animals, who often lead short and painful lives, are killed in ways that tend to minimise suffering. It is why cosmetic companies offer ‘cruelty free’ products, and why vegetarianism and veganism have become more popular in many countries. However, it is not always clear what truly counts as ‘suffering’ and therefore not always clear just how wide the moral circle should expand. Are there limits to whom, or what, our empathy should extend?

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Between Capitalism and the State-System

Quentin Bruneau in Phenomenal World:

How should we explain periods of profound global transformation? Scholars have long viewed socio-political change as a reflection of property relations and technological shifts in the productive process. They positioned capitalism as the principal force shaping world politics, with states broadly operating in the interest of maintaining capitalist social relations. In recent decades, however, a parallel tradition of thought has gained ground. In this tradition, the bureaucratic and military consolidation of states operates as the driver of economic relations, and international competition between states is the ultimate impulse for transformations within those same states. These two traditions of thought offer different accounts of the major challenges of our time, from climate change, to war, to austerity and sovereign debt. Should we understand these developments through the interests of capital, or should we instead conceive of them as the product of inter-state competition? The question is not merely of analytical interest; where we place emphasis directly informs the sort of solutions we envision to global problems. If climate change and war are the result of inter-state competition, greater cooperation can lead to a solution. If they are the result of capitalism, instead, they will remain unresolved until we do away with the economic system itself. In what follows, my aim is not to settle this discussion, but instead to revisit the debate over the relationship between capitalism and the states-system and introduce an important and overlooked turning point: the rise of Great Power politics. Ultimately, I argue that capitalism cannot subsume the dynamics of the states-system. In fact, it is itself derivative of a specific pattern of international ordering.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The new political theology

Arthur Goldhammer in Eurozine:

Is Charlie Kirk’s assassination-turned-martyrdom unofficially disestablishing the US constitutional clause against the government forming a national religion? And how astute would it be for diverse American sects to align their religious beliefs with Trump’s call for retribution? Even Pope Leo XIV has condemned the administration’s ‘unchristian’ policies.

After the assassination of Charlie Kirk, the Bible-quoting, radical right-wing political organizer, on 10 September 2025, the US president and his top officials moved quickly. In conjunction with Kirk’s widow and Turning Point USA, the political recruiting and Christian proselytizing organization Kirk founded, they staged a memorial extravaganza that combined lachrymose emotional display with Christological imagery and bellicose political rhetoric.

The First Amendment to the US Constitution states: ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.’ Strictly speaking, the Trump administration had not violated the letter of the Constitution. Congress had made no law.

But in making a martyr of Kirk, MAGA leaders exhibited a shrewd appreciation of one of the most profound insights of Alexis de Tocqueville, the nineteenth-century French historian and political theorist, who was the first and greatest student of American democracy: namely, that when it comes to guiding the evolution of democratic society, ‘mores are more important than laws’, where by ‘mores’ he meant not only ‘habits of the heart but also … the whole range of ideas that shape habits of mind … the whole moral and intellectual state of a people.’

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joseph Byrd (1937 – 2025) Experimental Composer and Musician

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Phil Upchurch (1941 – 2025) Guitarist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Kerala Has Abolished Extreme Poverty

Vijay Prashad in Scheerpost:

On 1 November 2025, the south-western Indian state of Kerala – home to 34 million people – was declared free from extreme poverty by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan. Kerala is one of the few places in the world to have eradicated extreme poverty, following China, which announced in 2022 that it had eradicated extreme poverty nationwide. Kerala’s achievement is significant for two reasons. First, in a country where hundreds of millions of people still live in poverty, Kerala is the only one of India’s twenty-eight states and eight union territories to have overcome extreme poverty. Second, Kerala is governed by the Communist-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) and is therefore routinely denied assistance from the central government led by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People’s Party).

On 1 November 2025, the south-western Indian state of Kerala – home to 34 million people – was declared free from extreme poverty by Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan. Kerala is one of the few places in the world to have eradicated extreme poverty, following China, which announced in 2022 that it had eradicated extreme poverty nationwide. Kerala’s achievement is significant for two reasons. First, in a country where hundreds of millions of people still live in poverty, Kerala is the only one of India’s twenty-eight states and eight union territories to have overcome extreme poverty. Second, Kerala is governed by the Communist-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) and is therefore routinely denied assistance from the central government led by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People’s Party).

Kerala’s Athidaridrya Nirmarjana Paripaadi (Extreme Poverty Eradication Project, or EPEP) was built on decades of worker and peasant struggles, which created strong public institutions and mass organisations, and the work of several left administrations. The EPEP was launched by Vijayan – a leader in the Communist Party of India (Marxist) – during the first Cabinet meeting of the second LDF government led by him in May 2021. After a rigorous criteria-based process focused on households’ access to employment, food, health, and housing, the government identified 64,006 families (or 103,099 individuals) as extremely poor. To carry out this survey, the government relied on about 400,000 enumerators – including government workers, cooperative members, and members of the mass organisations of left parties – to identify the unique problems faced by poor families. These enumerators created tailored plans for each family – from securing entitlements and accessing public services to obtaining housing, health care, and livelihood support – to build their strength in the fight against poverty. The role of the cooperative movement was fundamental in this campaign. The planning process for poverty eradication would not have been possible without the role of the local self-government system, the result of Kerala’s successful decentralisation of power. As this newsletter goes out, Kerala is in the midst of new local body elections.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

May I Explain the “May I Meet You?” Meme?

Katie Baker in The Ringer:

The way the fabled investor Bill Ackman sees it, he was born to move markets. It’s right there in the name: BILL-ionaire ACK-tivist MAN, as the 59-year-old always loves pointing out, whether in a New York magazine profile (in which Ackman also asserted that “I’ve met people named Hamburger that own McDonald’s franchises”) or on the social media platform X (where Ackman has racked up 1.8 million followers since he joined in 2017 with a Chipotle tweet). As a billionaire, an activist, and a man, Ackman built his fortune and his reputation by offering decades’ worth of unsolicited and even unwanted advice. Most of it has been directed toward the various big stagnant corporations he always sought to improve or the stubborn nations he still hopes to influence. But recently, Ackman has attempted to proffer his offbeat wisdom to us smol bean, stick-in-the-mud civilians, too.

The way the fabled investor Bill Ackman sees it, he was born to move markets. It’s right there in the name: BILL-ionaire ACK-tivist MAN, as the 59-year-old always loves pointing out, whether in a New York magazine profile (in which Ackman also asserted that “I’ve met people named Hamburger that own McDonald’s franchises”) or on the social media platform X (where Ackman has racked up 1.8 million followers since he joined in 2017 with a Chipotle tweet). As a billionaire, an activist, and a man, Ackman built his fortune and his reputation by offering decades’ worth of unsolicited and even unwanted advice. Most of it has been directed toward the various big stagnant corporations he always sought to improve or the stubborn nations he still hopes to influence. But recently, Ackman has attempted to proffer his offbeat wisdom to us smol bean, stick-in-the-mud civilians, too.

And more frequently, that wisdom has extended far beyond the field of finance.

“Just two cents from an older happily married guy concerned about our next generation’s happiness and population replacement rates,” Ackman posted this past weekend, using the same confident, conversational tone you might find in one of his hedge fund investor letters. “The online culture has destroyed the ability to spontaneously meet strangers. As such, I thought I would share a few words that I used in my youth to meet someone that I found compelling.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

The Case of Courage

No quality has ever so much addled the brains

and tangled the definitions of merely rational sages.

Courage is almost a contradiction in terms.

It means a strong desire to live taking the form of

a readiness to die.

‘He that will lose his life, the same shall save it,’

is not a piece of mysticism for saints and heroes.

It is a piece of everyday advice for sailors or mountaineers.

It might be printed in an Alpine guide or a drill book.

This paradox is the whole principle of courage;

even of quite earthly or brutal courage.

A man cut off by the sea may save his life

if he will risk it on the precipice.

He can only get away from death by

continually stepping within an inch of it.

A soldier surrounded by enemies,

if he is to cut his way out, needs to

combine a strong desire for living with a

strange carelessness about dying.

He must not merely cling to life, for then

he will be a coward, and will not escape.

He must not merely wait for death, for then

he will be a suicide, and will not escape.

He must seek his life in a spirit of furious

indifference to it; he must desire life

like water and yet drink death like wine.

by G.K. Chesterson

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, December 12, 2025

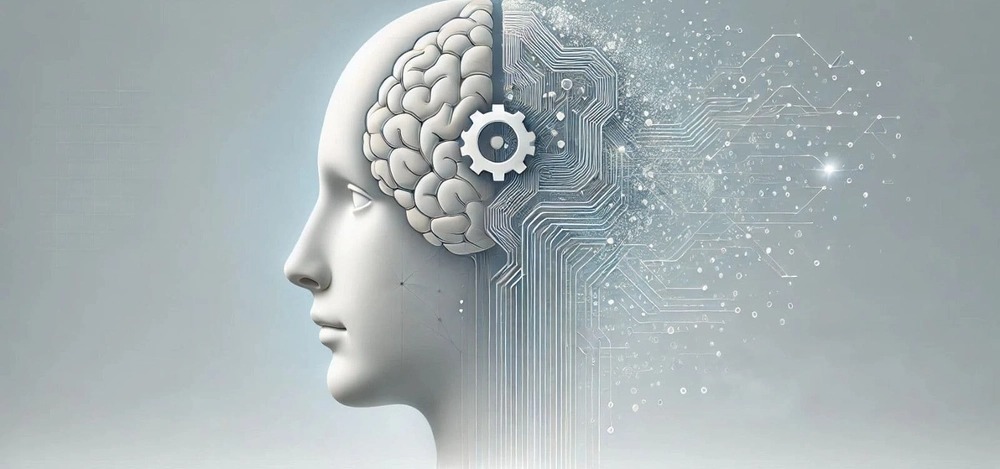

A Pragmatic View of AI Personhood

Paper by Joel Z. Leibo, Alexander Sasha Vezhnevets, William A. Cunningham, and Stanley M. Bileschi:

The emergence of agentic Artificial Intelligence (AI) is set to trigger a “Cambrian explosion” of new kinds of personhood. This paper proposes a pragmatic framework for navigating this diversification by treating personhood not as a metaphysical property to be discovered, but as a flexible bundle of obligations (rights and responsibilities) that societies confer upon entities for a variety of reasons, especially to solve concrete governance problems. We argue that this traditional bundle can be unbundled, creating bespoke solutions for different contexts. This will allow for the creation of practical tools—such as facilitating AI contracting by creating a target “individual” that can be sanctioned—without needing to resolve intractable debates about an AI’s consciousness or rationality. We explore how individuals fit in to social roles and discuss the use of decentralized digital identity technology, examining both ‘personhood as a problem’, where design choices can create “dark patterns” that exploit human social heuristics, and ‘personhood as a solution’, where conferring a bundle of obligations is necessary to ensure accountability or prevent conflict. By rejecting foundationalist quests for a single, essential definition of personhood, this paper offers a more pragmatic and flexible way to think about integrating AI agents into our society.

The emergence of agentic Artificial Intelligence (AI) is set to trigger a “Cambrian explosion” of new kinds of personhood. This paper proposes a pragmatic framework for navigating this diversification by treating personhood not as a metaphysical property to be discovered, but as a flexible bundle of obligations (rights and responsibilities) that societies confer upon entities for a variety of reasons, especially to solve concrete governance problems. We argue that this traditional bundle can be unbundled, creating bespoke solutions for different contexts. This will allow for the creation of practical tools—such as facilitating AI contracting by creating a target “individual” that can be sanctioned—without needing to resolve intractable debates about an AI’s consciousness or rationality. We explore how individuals fit in to social roles and discuss the use of decentralized digital identity technology, examining both ‘personhood as a problem’, where design choices can create “dark patterns” that exploit human social heuristics, and ‘personhood as a solution’, where conferring a bundle of obligations is necessary to ensure accountability or prevent conflict. By rejecting foundationalist quests for a single, essential definition of personhood, this paper offers a more pragmatic and flexible way to think about integrating AI agents into our society.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Australia’s world-first social media ban is a ‘natural experiment’ for scientists

Rachel Fieldhouse & Mohana Basu in Nature:

For Susan Sawyer, a physician-researcher specializing in adolescent health at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, the start of the social-media ban this week meant entering the next phase of her research. Over the past two months, Sawyer and her colleagues interviewed 177 teenagers aged 13–16 about their social-media use, screen time and mental health before the ban came into effect. She and her colleagues plan to survey the teenagers again in six months, to see whether the ban has affected their use of the platforms or their mental health. The researchers will also survey the participants’ parents about problematic Internet and social-media use by their children.

For Susan Sawyer, a physician-researcher specializing in adolescent health at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, the start of the social-media ban this week meant entering the next phase of her research. Over the past two months, Sawyer and her colleagues interviewed 177 teenagers aged 13–16 about their social-media use, screen time and mental health before the ban came into effect. She and her colleagues plan to survey the teenagers again in six months, to see whether the ban has affected their use of the platforms or their mental health. The researchers will also survey the participants’ parents about problematic Internet and social-media use by their children.

Another research collaboration between the Kids Research Institute Australia, the University of Western Australia and Edith Cowan University, all in Perth, will examine whether the ban is presenting new parenting challenges and what family conflicts have arisen as a result.

Amanda Third, a researcher at Western Sydney University in Australia who studies how children use technology, says the ban is an opportunity to collect data about the effect of policies that restrict young people’s access to the Internet and social media.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Normal distribution vs Power Laws

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Charles Dickens: A Short History with Tom Crewe

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.