Yascha Mounk at his Substack:

An awe-inspiring protest movement is shaking the foundations of power in Iran. Millions of people have taken to the streets to protest the corruption which has impoverished them, and the theocratic restrictions which have taken away their liberties. Men and especially women are standing up for their dignity and their livelihoods in the face of the deadly threat of state-sanctioned violence.

An awe-inspiring protest movement is shaking the foundations of power in Iran. Millions of people have taken to the streets to protest the corruption which has impoverished them, and the theocratic restrictions which have taken away their liberties. Men and especially women are standing up for their dignity and their livelihoods in the face of the deadly threat of state-sanctioned violence.

There are many reasons to fear that this protest movement could end badly. The regime could once again decide to crack down on its own citizens, killing dozens or hundreds or perhaps thousands of them in the process. (Indeed, according to eyewitness reports, it has already started doing so.) Power might shift from the ailing Ayatollah Khamenei to the Revolutionary Guards, perhaps lifting some restrictions on the country’s women but frustrating the broader political and economic aspirations of the population. Even a transition to democracy need not bring lasting results, as the failed experiments with democratic rule from Egypt to Tunisia prove.

But the sympathies of every single person who believes in freedom and equality and the basic rights of women should be with those courageous millions in Iran.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Editor:

Editor: The unsettling operation of worms is something science realized a long time ago. Drawing on observations by Charles Darwin and Otto August Mangold, Jakob von Uexküll

The unsettling operation of worms is something science realized a long time ago. Drawing on observations by Charles Darwin and Otto August Mangold, Jakob von Uexküll  LAS VEGAS — Just beyond the flashing slot machines and cigarette-saturated casino air, thousands of the health obsessed gathered in a convention hall here to demonstrate their hacks for living longer lives. They infused ozone into their blood streams, stood on vibrating mats, swallowed samples of supplements and took scans of their livers.

LAS VEGAS — Just beyond the flashing slot machines and cigarette-saturated casino air, thousands of the health obsessed gathered in a convention hall here to demonstrate their hacks for living longer lives. They infused ozone into their blood streams, stood on vibrating mats, swallowed samples of supplements and took scans of their livers. In recent years, the vagus nerve has become an object of fascination, especially on social media. The vagal nerve fibers, which run from the brain to the abdomen, have been anointed by some influencers as the key to reducing anxiety, regulating the nervous system and helping the body to relax.

In recent years, the vagus nerve has become an object of fascination, especially on social media. The vagal nerve fibers, which run from the brain to the abdomen, have been anointed by some influencers as the key to reducing anxiety, regulating the nervous system and helping the body to relax. I had a book come out last July. It was about a dead poet and it led to many speaking engagements (be careful what you wish for). Nearly every weekend during the fall semester of 2025, I was on the road or in the air. Once, on the water.

I had a book come out last July. It was about a dead poet and it led to many speaking engagements (be careful what you wish for). Nearly every weekend during the fall semester of 2025, I was on the road or in the air. Once, on the water. I opened Claude Code and gave it the command: “Develop a web-based or software-based startup idea that will make me $1000 a month where you do all the work by generating the idea and implementing it. i shouldn’t have to do anything at all except run some program you give me once. it shouldn’t require any coding knowledge on my part, so make sure everything works well.” The AI asked me three multiple choice questions and decided that I should be selling sets of 500 prompts for professional users for $39. Without any further input, it then worked independently… FOR AN HOUR AND FOURTEEN MINUTES creating hundreds of code files and prompts. And then it gave me a single file to run that created and deployed a working website (filled with very sketchy fake marketing claims) that sold the promised 500 prompt set.

I opened Claude Code and gave it the command: “Develop a web-based or software-based startup idea that will make me $1000 a month where you do all the work by generating the idea and implementing it. i shouldn’t have to do anything at all except run some program you give me once. it shouldn’t require any coding knowledge on my part, so make sure everything works well.” The AI asked me three multiple choice questions and decided that I should be selling sets of 500 prompts for professional users for $39. Without any further input, it then worked independently… FOR AN HOUR AND FOURTEEN MINUTES creating hundreds of code files and prompts. And then it gave me a single file to run that created and deployed a working website (filled with very sketchy fake marketing claims) that sold the promised 500 prompt set.  It’s been twenty years since your exhibition at La Maison Rouge. That was my first encounter with your work and it also marked a radical turning-point for the photographer you were at the time. How do you see that exhibition today?

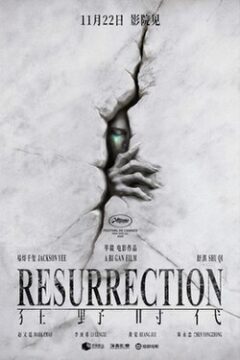

It’s been twenty years since your exhibition at La Maison Rouge. That was my first encounter with your work and it also marked a radical turning-point for the photographer you were at the time. How do you see that exhibition today? Films are rarely made in response to film critics, so it is unlikely that Bi Gan’s wildly ambitious new film was inspired Susan Sontag’s 1996 essay “The Decay of Cinema.” In any case, Bi was six years old, living in Kaili, China, when Sontag declared in The New York Times that “cinema’s 100 years seem to have the shape of a life cycle: an inevitable birth, the steady accumulation of glories and the onset in the last decade of an ignominious, irreversible decline.” “If cinema can be resurrected,” she concluded, “it will only be through the birth of a new kind of cine-love.” Yet Resurrection, as Bi’s film is called in English (its Chinese title is more like “Savage Age”—Bi has made a habit of giving his movies quite different titles in English and Chinese), seems conceived in exactly those terms. Its action spans that same century of movies, unified less by any continuity of plot than by the conviction that this era has come to an end. Cinema is dead. It may yet live again, but first: let us remember.

Films are rarely made in response to film critics, so it is unlikely that Bi Gan’s wildly ambitious new film was inspired Susan Sontag’s 1996 essay “The Decay of Cinema.” In any case, Bi was six years old, living in Kaili, China, when Sontag declared in The New York Times that “cinema’s 100 years seem to have the shape of a life cycle: an inevitable birth, the steady accumulation of glories and the onset in the last decade of an ignominious, irreversible decline.” “If cinema can be resurrected,” she concluded, “it will only be through the birth of a new kind of cine-love.” Yet Resurrection, as Bi’s film is called in English (its Chinese title is more like “Savage Age”—Bi has made a habit of giving his movies quite different titles in English and Chinese), seems conceived in exactly those terms. Its action spans that same century of movies, unified less by any continuity of plot than by the conviction that this era has come to an end. Cinema is dead. It may yet live again, but first: let us remember. In this circumstance, there is not so much a vacuum as a cloud of uncertainty. Everything is up in the air. Expectations, assumptions and intentions are scrambled. Fearing lost advantage in the face of these unknowns, worst-case scenarios drive the build-out of capabilities. Acting in the breach is a wild guess, the possible outcomes of which cannot be assuredly weighed.

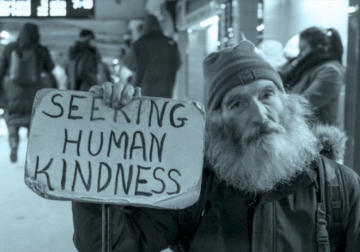

In this circumstance, there is not so much a vacuum as a cloud of uncertainty. Everything is up in the air. Expectations, assumptions and intentions are scrambled. Fearing lost advantage in the face of these unknowns, worst-case scenarios drive the build-out of capabilities. Acting in the breach is a wild guess, the possible outcomes of which cannot be assuredly weighed. Baghdad was cloaked in its familiar shroud of darkness when, in early October, I walked the al-Shuhada Bridge across the Tigris—more a ritual for me than a pastime. Long before Walter Benjamin described the Seine as “the vast and ever-watchful mirror of Paris,” the Andalusian traveler Ibn Jubayr saw the Tigris as “a mirror shining between two frames, or like a string of pearls between two breasts.” That image of splendor has long since dissipated. On the bridge that night, I passed by an old woman in her abaya sat begging on the curb; plastic waste lined the shallow waters below.

Baghdad was cloaked in its familiar shroud of darkness when, in early October, I walked the al-Shuhada Bridge across the Tigris—more a ritual for me than a pastime. Long before Walter Benjamin described the Seine as “the vast and ever-watchful mirror of Paris,” the Andalusian traveler Ibn Jubayr saw the Tigris as “a mirror shining between two frames, or like a string of pearls between two breasts.” That image of splendor has long since dissipated. On the bridge that night, I passed by an old woman in her abaya sat begging on the curb; plastic waste lined the shallow waters below.