Gregory Hickok in Psychology Today:

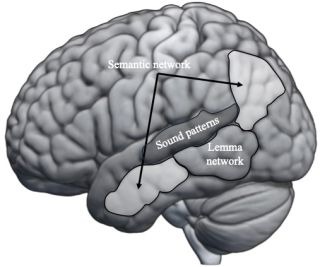

How is it that words can be so common, so fundamental, yet so elusive? A key discovery is that words are not just a sound pattern (cat, gato, neko) and a meaning (furry-domesticated-meows), but also contain something in between, a kind of “middle word,” which psycholinguists refer to as a lemma. The name comes from mathematics, where it refers to an intermediate step in a theorem. You can think of word lemmas as the hidden network that computes the translation between word sound and word meaning. How do we know lemmas exist? There are several bits of evidence, including computational arguments, neural network simulations, and behavioral studies showing that when people get themselves into tip-of-the-tongue states—a failure to access the sound pattern of a word—they know more about the word than just its meaning, such as fragments of its syntactic properties. There’s another fascinating source of evidence, though: neurological cases in which people appear to have lost their middle-word realm altogether.

How is it that words can be so common, so fundamental, yet so elusive? A key discovery is that words are not just a sound pattern (cat, gato, neko) and a meaning (furry-domesticated-meows), but also contain something in between, a kind of “middle word,” which psycholinguists refer to as a lemma. The name comes from mathematics, where it refers to an intermediate step in a theorem. You can think of word lemmas as the hidden network that computes the translation between word sound and word meaning. How do we know lemmas exist? There are several bits of evidence, including computational arguments, neural network simulations, and behavioral studies showing that when people get themselves into tip-of-the-tongue states—a failure to access the sound pattern of a word—they know more about the word than just its meaning, such as fragments of its syntactic properties. There’s another fascinating source of evidence, though: neurological cases in which people appear to have lost their middle-word realm altogether.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A container ship looks like a perfect place for a nuclear reactor, from a technology standpoint. But a lawyer might call it the worst. It’s a good example of the divergence between what the world needs, and what the world can get.

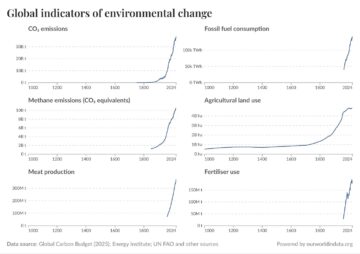

A container ship looks like a perfect place for a nuclear reactor, from a technology standpoint. But a lawyer might call it the worst. It’s a good example of the divergence between what the world needs, and what the world can get. My argument is simple: for the first time in history, we can improve human wellbeing while reducing our environmental impact.

My argument is simple: for the first time in history, we can improve human wellbeing while reducing our environmental impact. How monogamous are humans, really? It’s an age-old question subject to significant debate. Now a University of Cambridge professor has an answer: Somewhere between the Eurasian beaver and a meerkat. That’s according to a new study in the journal

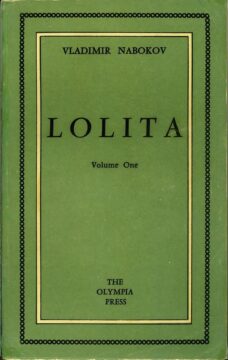

How monogamous are humans, really? It’s an age-old question subject to significant debate. Now a University of Cambridge professor has an answer: Somewhere between the Eurasian beaver and a meerkat. That’s according to a new study in the journal  The long tradition of carceral creativity goes back centuries: John Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress, Boethius The Consolation of Philosophy, and Oscar Wilde De Profundis all while behind bars. The lineage continued into modern times with Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, and, of course, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote an entire novel on toilet paper in his prison cell.

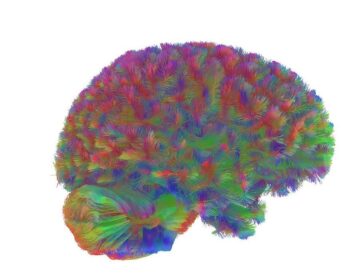

The long tradition of carceral creativity goes back centuries: John Bunyan wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress, Boethius The Consolation of Philosophy, and Oscar Wilde De Profundis all while behind bars. The lineage continued into modern times with Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, and, of course, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wrote an entire novel on toilet paper in his prison cell. For the study, scientists combined nine previously collected datasets to look at the brain scans of almost 4,000 “neurotypical” individuals, from newborns to 90-year-olds. Specifically, they looked at diffusion MRI scans, which measure the microscopic movements of water molecules inside the brain. These scans show how the organ’s tissues are structured and can also be used to detect subtle changes, allowing the researchers to see how average brain architecture evolves over a lifetime.

For the study, scientists combined nine previously collected datasets to look at the brain scans of almost 4,000 “neurotypical” individuals, from newborns to 90-year-olds. Specifically, they looked at diffusion MRI scans, which measure the microscopic movements of water molecules inside the brain. These scans show how the organ’s tissues are structured and can also be used to detect subtle changes, allowing the researchers to see how average brain architecture evolves over a lifetime. In Jim Fishkin’s

In Jim Fishkin’s  Writing à propos of Louis Armand’s recent opus magnum, A Tomb in H-Section (2025), critic Ramiro Sanchiz called it “a necromodernist tour de force which animates every remain of (un)dead XXth century literature,” thus invoking the spectre of necromodernism, a modernism long-buried but still somehow living on, its undead corpse back again for yet another zombie standoff. In a similar vein, the publisher note described the tome as “a vast, complex book object that concentrates the synergies of Louis Armand’s Golemgrad Pentalogy, of which it is at once a crowning achievement and a jocoserious deconstruction — an ‘Armandgeddon,’ if you will.”

Writing à propos of Louis Armand’s recent opus magnum, A Tomb in H-Section (2025), critic Ramiro Sanchiz called it “a necromodernist tour de force which animates every remain of (un)dead XXth century literature,” thus invoking the spectre of necromodernism, a modernism long-buried but still somehow living on, its undead corpse back again for yet another zombie standoff. In a similar vein, the publisher note described the tome as “a vast, complex book object that concentrates the synergies of Louis Armand’s Golemgrad Pentalogy, of which it is at once a crowning achievement and a jocoserious deconstruction — an ‘Armandgeddon,’ if you will.” “Let Paul Robeson singing Water Boy and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem … cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” So wrote Langston Hughes in his landmark 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Today, Paul Robeson—singer, actor, athlete, lawyer, antiracism icon—needs no introduction. But who was Rudolph Fisher?

“Let Paul Robeson singing Water Boy and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem … cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.” So wrote Langston Hughes in his landmark 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” Today, Paul Robeson—singer, actor, athlete, lawyer, antiracism icon—needs no introduction. But who was Rudolph Fisher? A

A  We live in a world created by capitalism. The ceaseless accumulation of capital forges the cities we inhabit, determines the way we work, allows an extraordinarily large number of people to engage in unprecedented levels of consumption, influences our politics, and shapes the landscapes around us. It is impossible to look at Earth and miss the world‑historical force of capitalism.

We live in a world created by capitalism. The ceaseless accumulation of capital forges the cities we inhabit, determines the way we work, allows an extraordinarily large number of people to engage in unprecedented levels of consumption, influences our politics, and shapes the landscapes around us. It is impossible to look at Earth and miss the world‑historical force of capitalism. In mathematics,

In mathematics,