You have to imagine it:

______________

Who said you were too dark/too

Large? Too queer/too loud?

______________

Who said you were too poor/

Too strange? Too fat?

______________

You have to imagine it:

______________

Who said you must keep quiet?

Who heard your story, then

Rolled their eyes?

______________

Who tried to change your name

To invisible?

______________

You’ve got to imagine:

______________

Who heard your name

And refused to pronounce it?

Who checked their watch

And said “not now”?

______________

James Baldwin wrote:

______________

“The place in which I’ll fit

Will not exist

Until I make it.”

______________

New York, city of invention,

Roiling town, refresher

And re-newer,

______________

New York, city of the real,

Where the canyons

Whisper in a hundred

Tongues,

______________

New York,

Where your lucky self

Waits for your

Arrival,

______________

Where there is always soil

For your root.

______________

This is our time.

______________

The taste of us/the spice of us

The hollers and the rhythms and

The beats of us.

______________

In the echo of our

Ancestors,

Who made certain we know

Who we are.

______________

City of Insistence,

City of Resistance,

______________

You have to imagine:

______________

An Army that wins without

Firing a bullet,

A joy that wears down

The rock of no.

______________

Up from insults,

Up from blocked doors,

Up from trick bags,

Up from fear/up from shame,

Up from the way it was done before.

______________

You have to imagine:

______________

That space they said wasn’t yours.

That time they said you’d never own.

The invisible city lit, on its way.

______________

This moment is our proof.

James Robinson is a professor at the University of Chicago and a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2024. Jim has been a friend for many decades and was for some time my colleague in Berkeley. This conversation is in 2 parts. Below you’ll find four questions by me and Jim’s response to them. The second part, consisting of four more questions and his answers, will be posted next week. I should mention here that by ‘institutions’ economists generally mean the social rules, conventions and other elements of the structural framework of socio-economic interaction.

James Robinson is a professor at the University of Chicago and a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2024. Jim has been a friend for many decades and was for some time my colleague in Berkeley. This conversation is in 2 parts. Below you’ll find four questions by me and Jim’s response to them. The second part, consisting of four more questions and his answers, will be posted next week. I should mention here that by ‘institutions’ economists generally mean the social rules, conventions and other elements of the structural framework of socio-economic interaction.

Having authored a multitude of fiction and nonfiction works, Howard University alumna and professor

Having authored a multitude of fiction and nonfiction works, Howard University alumna and professor  Artificial intelligence has rapidly become a central arena of geopolitical competition. The United States government frames AI as a strategic asset on par with energy or defense and seeks to press its apparent lead in developing the technology. The European Union lags in platform power but seeks influence over AI through regulation, labor protections, and rule-setting. China is racing to catch up and to deploy AI at scale, combining heavy state investment with administrative control and surveillance.

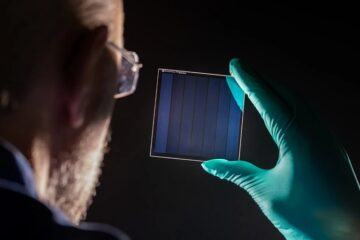

Artificial intelligence has rapidly become a central arena of geopolitical competition. The United States government frames AI as a strategic asset on par with energy or defense and seeks to press its apparent lead in developing the technology. The European Union lags in platform power but seeks influence over AI through regulation, labor protections, and rule-setting. China is racing to catch up and to deploy AI at scale, combining heavy state investment with administrative control and surveillance. Hidden inside every swipe, search, and AI prompt is a fingernail-sized slab of silicon — etched with billions of switches — built in $20 billion factories using machines so precise they border on science fiction. And because only a handful of companies (and a few chokepoint countries) can make the most advanced chips, the semiconductor supply chain has become the real front line of the AI race and U.S.–China competition.

Hidden inside every swipe, search, and AI prompt is a fingernail-sized slab of silicon — etched with billions of switches — built in $20 billion factories using machines so precise they border on science fiction. And because only a handful of companies (and a few chokepoint countries) can make the most advanced chips, the semiconductor supply chain has become the real front line of the AI race and U.S.–China competition. Johns Hopkins is launching its 150th anniversary celebration. When it was founded in 1876, American universities were still mostly finishing schools for children of the nation’s elite. Hopkins introduced the modern research university to the US, importing the model from Germany, helping reshape American higher education in its image.

Johns Hopkins is launching its 150th anniversary celebration. When it was founded in 1876, American universities were still mostly finishing schools for children of the nation’s elite. Hopkins introduced the modern research university to the US, importing the model from Germany, helping reshape American higher education in its image. The rules of Japan’s national sport are relatively straightforward: two rikishi—literally, “strong men”—face each other near the center of the ring, crouched on their haunches, like plus-size sprinters waiting to explode out of the starting block. They will often squat and then rise to stamp their feet or throw salt on the ground. When the referee signals the start of the match, they rush toward each other and collide with the same force that a person might absorb after falling from a height of two or three stories. From their fleshy collision, one man tends to emerge with the advantage of surer footing or a firmer grip on his opponent’s loincloth, known as a mawashi, which wrestlers can use to lift and toss each other around the ring. Whoever can force his adversary from the ring or get any part of his body other than the soles of his feet to touch the ground is the winner.

The rules of Japan’s national sport are relatively straightforward: two rikishi—literally, “strong men”—face each other near the center of the ring, crouched on their haunches, like plus-size sprinters waiting to explode out of the starting block. They will often squat and then rise to stamp their feet or throw salt on the ground. When the referee signals the start of the match, they rush toward each other and collide with the same force that a person might absorb after falling from a height of two or three stories. From their fleshy collision, one man tends to emerge with the advantage of surer footing or a firmer grip on his opponent’s loincloth, known as a mawashi, which wrestlers can use to lift and toss each other around the ring. Whoever can force his adversary from the ring or get any part of his body other than the soles of his feet to touch the ground is the winner. How does one start Infinite Jest? In the year 2026, thirty years after its initial release, the book is a distinctive cultural object. It has been memed to oblivion, its author eulogized and criticized and transformed into an enormous posthumous celebrity. Infinite Jest has a reputation for being brilliant, transcendent, transformative, genius. But it’s also thought to be tricky, long, confusing, pretentious, unfashionably male, and embarrassing to read on the subway. “There’s that horrible joke: ‘If you go to a guy’s house and he has a copy of Infinite Jest, don’t fuck him,’ ” Sarah McNally, the owner of McNally Jackson, told me. “I profoundly disagree with that,” she added, laughing. To the contrary, she said, she finds the book quite “seductive.”

How does one start Infinite Jest? In the year 2026, thirty years after its initial release, the book is a distinctive cultural object. It has been memed to oblivion, its author eulogized and criticized and transformed into an enormous posthumous celebrity. Infinite Jest has a reputation for being brilliant, transcendent, transformative, genius. But it’s also thought to be tricky, long, confusing, pretentious, unfashionably male, and embarrassing to read on the subway. “There’s that horrible joke: ‘If you go to a guy’s house and he has a copy of Infinite Jest, don’t fuck him,’ ” Sarah McNally, the owner of McNally Jackson, told me. “I profoundly disagree with that,” she added, laughing. To the contrary, she said, she finds the book quite “seductive.” Most people recognise the experience. A solemn setting. Absolute

Most people recognise the experience. A solemn setting. Absolute  Researchers at Microsoft have created a data-storage system that can remain readable for at least 10,000 years — and probably much longer.

Researchers at Microsoft have created a data-storage system that can remain readable for at least 10,000 years — and probably much longer. It is five years since I was exiled. My own erasure must be underway. Though for a long time I resisted settling in the US, I now live in New York. If I’m ever able to return to Cárdenas, it will surely be as an intruder in my own town; another ambassador from a foreign society. While the government or the military banish you deliberately, ordinary people can do the same through indifference – a form of cruelty that can’t be blamed on anyone in particular because, in truth, nobody wills it.

It is five years since I was exiled. My own erasure must be underway. Though for a long time I resisted settling in the US, I now live in New York. If I’m ever able to return to Cárdenas, it will surely be as an intruder in my own town; another ambassador from a foreign society. While the government or the military banish you deliberately, ordinary people can do the same through indifference – a form of cruelty that can’t be blamed on anyone in particular because, in truth, nobody wills it.