Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

A Measure of Things Human

In March 1988, the late Israeli historian Yehuda Elkana, an Auschwitz survivor, published an explosive op-ed in Haaretz on “the need to forget.” He wrote that although he often spoke of the Holocaust to his four children and freely shared his personal recollections of it with them, he had refused to accompany them on visits to Yad Vashem. He had been reluctant to follow the Eichmann trial and he opposed the trial of John Demjanjuk, who had been a guard at the Sobibor death camp and was awaiting sentencing then. Elkana was convinced that the memory of the Holocaust had been co-opted for destructive ends, that it had been maliciously harnessed to fuel hatred and violence against the Palestinian people.

In March 1988, the late Israeli historian Yehuda Elkana, an Auschwitz survivor, published an explosive op-ed in Haaretz on “the need to forget.” He wrote that although he often spoke of the Holocaust to his four children and freely shared his personal recollections of it with them, he had refused to accompany them on visits to Yad Vashem. He had been reluctant to follow the Eichmann trial and he opposed the trial of John Demjanjuk, who had been a guard at the Sobibor death camp and was awaiting sentencing then. Elkana was convinced that the memory of the Holocaust had been co-opted for destructive ends, that it had been maliciously harnessed to fuel hatred and violence against the Palestinian people.

He published his piece when he did—in the midst of the first intifada, not long after footage emerged of Israeli soldiers beating bound and blindfolded Palestinians—perhaps hoping there was still time to reverse course. He explicitly argued that “had the Holocaust not penetrated so deeply into the national consciousness,” the conflict between Jews and Palestinians would not have produced acts of terrorism and abject violence; he even conjectured that the peace process might not have stalled. For Elkana, the time had finally come for the Jewish people to abandon the belief “that the whole world is against us, and that we are the eternal victim.” While the wider world could very well continue to remember the Holocaust, Israelis now had to forget: “Today I see no more important political and educational task for the leaders of this nation than to take their stand on the side of life, to dedicate themselves to creating our future, and not to be preoccupied, morning to night, with symbols, ceremonies, and lessons of the Holocaust.” Democracy, Elkana warned, was at risk when “the memory of the dead participates actively in the democratic process”—when politics becomes a pathway for unending revenge.

The essay was an attempt to prevent his nation from continuing down a catastrophic path of inexcusable violence fueled by existential pain and panic.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Nietzsche and Dionysus

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

Beautiful Silence Endless Talking

If your name is Omar nobody in the town of Kash

will sell you a loaf of bread, at any price.

You go to a bakery shop and say, “Hello, my name is Omar.

I’d like some bread.” The baker will reply, “Try the shop

down the street. One loaf of his bread is better than fifty of mine.”

But if you have healed your eyesight of all duality,

You can answer, “There is no other bakery!”

The illumination of that would blind the baker

and change your name.

As it is, the bakers a Kash nod, and with tones of voice

they know, send you on wild-goose chase around town.

Once you have said your name is “Omar” in one shop,

you may as well quit trying to buy bread in Kash.

You’re not only seeing double. You’re seeing ten-fold!

And you’ll never get fed.

You move from nook to nook in the ruins of a monastery,

thinking, The next prayer-place is the place I’m looking for.

Let your eyes see God everywhere. Give up fears

and expectations. The friend, the Beloved, your soul,

is a river with the trees and buds of the world

reflected in it. And it’s no illusion!

The reflections are real, real images, through which

God is made real to you. The River Water

is an orchard that fills your basket.

But not all flowings are the same. Different donkeys

take different loads and different persuasive sticks.

One principle does not apply to all rivers.

For example, inside this river there is a moon

which is not a reflection!

From the riverbottom the Moon speaks,

………………………………………………………….“I travel

in continuous conversation with the river as it goes.

whatever is above and seemingly outside this river

is actually in it. It all belongs to the Friend.”

Merge with it, in here or out there, as you please,

because this is the river of rivers

and the beautiful silence of Endless Talking.

by Rumi

from We Are Three

Coleman Barks, 1987

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How AI Can Help Save Our Oceans

Vivien Walt in Time Magazine:

At this week’s U.N. Oceans Conference in the south of France, delegates need only glance outside the conference hall at the glittering Mediterranean for a stark reminder of the problem they are trying to solve. Scientists estimate there are now about 400 ocean “dead zones” in the world, where no sea life can survive—more than double the number 20 years ago. The oceans, which cover 70% of Earth and are crucial to mitigating global warming, will likely contain more tonnage of plastic junk than fish by 2050. And by 2100, about 90% of marine species could be extinct.

At this week’s U.N. Oceans Conference in the south of France, delegates need only glance outside the conference hall at the glittering Mediterranean for a stark reminder of the problem they are trying to solve. Scientists estimate there are now about 400 ocean “dead zones” in the world, where no sea life can survive—more than double the number 20 years ago. The oceans, which cover 70% of Earth and are crucial to mitigating global warming, will likely contain more tonnage of plastic junk than fish by 2050. And by 2100, about 90% of marine species could be extinct.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Cryptic Female Choice Shapes the Evolution of Species

Hannah Thomasy in The Scientist:

The cellular biology of reproduction is often depicted as an epic journey, in which millions of intrepid sperm fight to be the first to claim the ultimate prize: the chance to fertilize the egg, which has been passively waiting for the sperm to arrive. But is this an accurate picture? In a 1991 paper, New York University anthropologist Emily Martin argued that this notion was, in fact, “a scientific fairy tale.”1 Instead of representing absolute unbiased truths, she asserted that, “The picture of egg and sperm drawn in popular as well as scientific accounts of reproductive biology relies on stereotypes central to our cultural definitions of male and female.”

The cellular biology of reproduction is often depicted as an epic journey, in which millions of intrepid sperm fight to be the first to claim the ultimate prize: the chance to fertilize the egg, which has been passively waiting for the sperm to arrive. But is this an accurate picture? In a 1991 paper, New York University anthropologist Emily Martin argued that this notion was, in fact, “a scientific fairy tale.”1 Instead of representing absolute unbiased truths, she asserted that, “The picture of egg and sperm drawn in popular as well as scientific accounts of reproductive biology relies on stereotypes central to our cultural definitions of male and female.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘A Trick of the Mind’ by Daniel Yon

Huw Green at The Guardian:

The process of perception feels quite passive. We open our eyes and light floods in; the world is just there, waiting to be seen. But in reality there is an active element that we don’t notice. Our brains are always “filling in” our perceptual experience, supplementing incoming information with existing knowledge. For example, each of us has a spot at the back of our eye where there are no light receptors. We don’t see the resulting hole in our field of vision because our brains ignore it. The phenomenon we call “seeing” is the result of a continuously updated model in your mind, made up partly of incoming sensory information, but partly of pre-existing expectations. This is what is meant by the counterintuitive slogan of contemporary cognitive science: “perception is a controlled hallucination”.

The process of perception feels quite passive. We open our eyes and light floods in; the world is just there, waiting to be seen. But in reality there is an active element that we don’t notice. Our brains are always “filling in” our perceptual experience, supplementing incoming information with existing knowledge. For example, each of us has a spot at the back of our eye where there are no light receptors. We don’t see the resulting hole in our field of vision because our brains ignore it. The phenomenon we call “seeing” is the result of a continuously updated model in your mind, made up partly of incoming sensory information, but partly of pre-existing expectations. This is what is meant by the counterintuitive slogan of contemporary cognitive science: “perception is a controlled hallucination”.

A century ago, someone with an interest in psychology might have turned to the work of Freud for an overarching vision of how the mind works. To the extent there is a psychological theory even remotely as significant today, it is the “predictive processing” hypothesis.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin

Jennifer Szalai at the NY Times:

For much of his life, Paul Gauguin railed against the deadening effects of bourgeois domesticity. But as Sue Prideaux writes in “Wild Thing,” her terrific new biography of the artist, for about a decade early in his career the self-proclaimed “savage from Peru” enjoyed a stint as a happily married stockbroker in Paris.

For much of his life, Paul Gauguin railed against the deadening effects of bourgeois domesticity. But as Sue Prideaux writes in “Wild Thing,” her terrific new biography of the artist, for about a decade early in his career the self-proclaimed “savage from Peru” enjoyed a stint as a happily married stockbroker in Paris.

His wife, Mette, was an independent-minded woman from Denmark. Gauguin spent his free time making art, drawing obsessively and learning how to paint and sculpt. He could afford to be “carelessly rich, gleefully opulent,” Prideaux writes, noting that his possessions included 12 paintings by Cézanne and 14 pairs of pants. “Art was his mistress. Mette was his wife. He was content.” A stock market crash in 1882 upended all that. Gauguin lost his job and had to scramble to find a way to support his family, which soon included five children. They all moved to Denmark, where he sold tarpaulins. He found life there to be stuffy to the point of stultifying. He realized he had to leave. “I only want to paint,” he wrote to a friend. “Everybody hates me because I paint but it is the only thing I can do.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, June 12, 2025

Cy Twombly was all over New York and Dean Rader was there to see it

Dean Rader in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

I begin with some questions. What is the difference between writing and drawing? What distinguishes seeing from reading? Can a painting be illegible? Can you write a drawing? In what ways can writing resist erasure and yet also be a mode of erasure? These are the dilemmas that haunt me when I think of the work of Cy Twombly, one of the United States’ most enigmatic artists.

I begin with some questions. What is the difference between writing and drawing? What distinguishes seeing from reading? Can a painting be illegible? Can you write a drawing? In what ways can writing resist erasure and yet also be a mode of erasure? These are the dilemmas that haunt me when I think of the work of Cy Twombly, one of the United States’ most enigmatic artists.

Twombly (1928–2011) has been a polarizing figure. He is best known for his large scrawly works in grayscale, sometimes called “blackboard paintings,” that resemble the marks of a second grader trying to learn cursive and failing. The artist has drawn (ha!) admiration from some of the greatest writers and critics of our era, from Roland Barthes and Robert Motherwell to Octavio Paz and Anne Carson. Yet few artists have also been on the end of more ridicule. Donald Judd called an early exhibit of Twombly’s “a fiasco.” Jackson Arn described a Twombly series from 2003 as “too repetitively cheery to be engaging, like a bad series of children’s books.” In 1994, when the Museum of Modern Art hosted a Twombly retrospective, Artforum ran competing takes on Twombly’s oeuvre titled “Cy’s Up” and “Size Down,” in which the venerable scholar Rosalind E. Krauss and Peter Schjeldahl (who would go on to be the art critic at The New Yorker) squared off.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Google’s nightmare: How a search spinoff could remake the web

Ryan Whitwam at Ars Technica:

Google wasn’t around for the advent of the World Wide Web, but it successfully remade the web on its own terms. Today, any website that wants to be findable has to play by Google’s rules, and after years of search dominance, the company has lost a major antitrust case that could reshape both it and the web.

Google wasn’t around for the advent of the World Wide Web, but it successfully remade the web on its own terms. Today, any website that wants to be findable has to play by Google’s rules, and after years of search dominance, the company has lost a major antitrust case that could reshape both it and the web.

The closing arguments in the case just wrapped up last week, and Google could be facing serious consequences when the ruling comes down in August. Losing Chrome would certainly change things for Google, but the Department of Justice is pursuing other remedies that could have even more lasting impacts. During his testimony, Google CEO Sundar Pichai seemed genuinely alarmed at the prospect of being forced to license Google’s search index and algorithm, the so-called data remedies in the case. He claimed this would be no better than a spinoff of Google Search. The company’s statements have sometimes derisively referred to this process as “white labeling” Google Search.

But does a white label Google Search sound so bad? Google has built an unrivaled index of the web, but the way it shows results has become increasingly frustrating. A handful of smaller players in search have tried to offer alternatives to Google’s search tools. They all have different approaches to retrieving information for you, but they agree that spinning off Google Search could change the web again. Whether or not those changes are positive depends on who you ask.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Paul Bloom joins Brian Greene for a spirited exploration of consciousness, memory, empathy, free will, and the elusive workings of the human mind

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

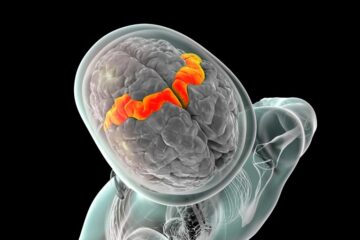

World first: brain implant lets man speak with expression — and sing

Miryam Naddaf in Nature:

A man with a severe speech disability is able to speak expressively and sing using a brain implant that translates his neural activity into words almost instantly. The device conveys changes of tone when he asks questions, emphasizes the words of his choice and allows him to hum a string of notes in three pitches.

A man with a severe speech disability is able to speak expressively and sing using a brain implant that translates his neural activity into words almost instantly. The device conveys changes of tone when he asks questions, emphasizes the words of his choice and allows him to hum a string of notes in three pitches.

The system — known as a brain–computer interface (BCI) — used artificial intelligence (AI) to decode the participant’s electrical brain activity as he attempted to speak. The device is the first to reproduce not only a person’s intended words but also features of natural speech such as tone, pitch and emphasis, which help to express meaning and emotion. In a study, a synthetic voice that mimicked the participant’s own spoke his words within 10 milliseconds of the neural activity that signalled his intention to speak. The system, described today in Nature1, marks a significant improvement over earlier BCI models, which streamed speech within three seconds or produced it only after users finished miming an entire sentence.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Roger Penrose – Why Intelligence Is Not a Computational Process

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

If It’s Worth Your Time To Lie, It’s Worth My Time To Correct It

Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten:

If you say Joe Criminal committed ten murders and five rapes, and I object that it was actually only six murders and two rapes, then why am I “defending” Joe Criminal?

If you say Joe Criminal committed ten murders and five rapes, and I object that it was actually only six murders and two rapes, then why am I “defending” Joe Criminal?

Because if it’s worth your time to lie, it’s worth my time to correct it.

If one side lies to make all of their arguments sound 5% stronger, then over long enough it adds up. Unless they want to be left behind, the other side has to make all of their arguments 5% stronger too. Then there’s a new baseline – why not 10%? Why not 20%? This mechanism might sound theoretical when I describe it this way, but go to any space where corrections are discouraged, and you will see exactly this.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Marquis De Sade and The 120 Days of Sodom

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In Times of Change: Five Short Japanese Novels

Asako Serizawa at the Hudson Review:

There is a certain privilege in looking at a group of novels-in-translation from a single country originally written and published across almost a century. What appears at first glance to be a disparate assortment of texts gathered solely by the date of their reissue in a new language reveals an unexpected coherence. That the following five short Japanese novels-in-translation are being made available to a wider audience now, in the middle of the 2020s, feels timely.

There is a certain privilege in looking at a group of novels-in-translation from a single country originally written and published across almost a century. What appears at first glance to be a disparate assortment of texts gathered solely by the date of their reissue in a new language reveals an unexpected coherence. That the following five short Japanese novels-in-translation are being made available to a wider audience now, in the middle of the 2020s, feels timely.

Whether written under overt authoritarian censorship or under the disempowering pressures of late modernity, these texts, taken together, beg the question of what art’s role might be in liminal times, what it can do—what should it do? Originally published in 1927, Kappa[1] is one of the last works Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1892–1927), perhaps best known in the English-speaking world for “Rashōmon” (1915), wrote before his death later that year at the age of thirty-five.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Jane Austen Pulled It Off: On Emma

Jennifer Egan at the Paris Review:

One of Jane Austen’s many mind-bending skills was her ability to wrest so much drama from a world that was, by present-day standards, almost unfathomably static. Austen’s novels are preindustrial time capsules from an era before even trains, gas lights, or telegraphs—the first in a stampede of inventions that transformed nineteenth-century life and are vividly present in the work of many novelists emblematic of that century. Born in 1775, a year before American Independence, Austen has preserved for us an epoch when indoor illumination required candles, remote communication took place by messenger or mail, and locomotion meant walking or engaging at least one horse—more if, like Emma’s protagonist and namesake (and indeed every woman in that novel), you didn’t ride, and needed a carriage to travel any distance.

One of Jane Austen’s many mind-bending skills was her ability to wrest so much drama from a world that was, by present-day standards, almost unfathomably static. Austen’s novels are preindustrial time capsules from an era before even trains, gas lights, or telegraphs—the first in a stampede of inventions that transformed nineteenth-century life and are vividly present in the work of many novelists emblematic of that century. Born in 1775, a year before American Independence, Austen has preserved for us an epoch when indoor illumination required candles, remote communication took place by messenger or mail, and locomotion meant walking or engaging at least one horse—more if, like Emma’s protagonist and namesake (and indeed every woman in that novel), you didn’t ride, and needed a carriage to travel any distance.

Austen’s fourth published novel is the most physically constricted of her works, which makes it also the most virtuosic. Unlike Austen’s other protagonists, Emma Woodhouse never spends a night away from home. That home is in fictional Highbury, “a large and populous village almost amounting to a town,” whose sixteen-mile distance from London might as well be six hundred.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

…. Cedar Waxwing, Pyracantha II

Here are the ones I think will come: Wren, chestnut backed chickadee, hairy woodpecker, scrub jay. Words of a dream retold dissolve into pulp, into seed glue. Into chips of memory. This morning, I’ve a soft waxwing in hand. We are both stunned. His eye is cast beyond currents or cadence. He is shallow breath and a curled foot, tucked and gnarled. The purple stain I mistook for blood is rather three berries athroat bruised and slowly oozing. Berry juice tattoos his chin, small foot, my spring fingers. I remember thinking to hack down the pyracantha when all I could hear were thorns. If I listen long enough to form a new ear, I would press it low to the damp earth. There, the thrum of bacteria tickling roots might tap a rhythm I forgot to remember. Soft numb resilience, wing me a story. Scratch me a skin poem. Chase the sparrow’s tail, roll the boulder. Convince my hemoglobin. Take the spirit from the palm or cedar waxwing pluck the berry or hummingbird sip the nectar. Stillness and furious flight, one perfect circle. I dip thumb into water and droplet him back to consciousness. For a moment we are eye to eye—then we alight.

by Lehua M. Taitano

from Split This RockEnjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, June 11, 2025

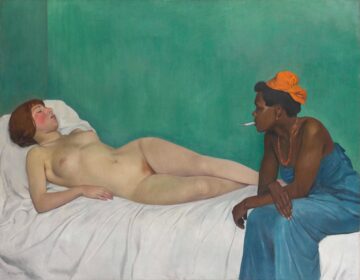

The colorful imagination of Félix Vallotton

Brooks Riley in Art At First Sight:

Sometimes it pays to spend more time in the detours of art history—leaving behind the rigor mortis of the canon to follow new pathways—not necessarily toward an alternative canon, but to discover forgotten artists deserving of more attention.

Sometimes it pays to spend more time in the detours of art history—leaving behind the rigor mortis of the canon to follow new pathways—not necessarily toward an alternative canon, but to discover forgotten artists deserving of more attention.

The half-century of art between 1880 and 1930 was explosively innovative, with a burgeoning middle class now taking up the joys of painting, birthing multiple new ‘isms’—painters extricating themselves from the myopic, bourgeois poetry of impressionism and probing in all directions with anarchic glee, as they tried to find their single voice within the noise of impending modernism.

One of those painters was the Swiss artist Félix Vallotton. For reasons that I am still trying to figure out, I have fallen for the works of Vallotton, not a household name in art history, but one of the most perplexing and intriguing artists of the period. There is no nutshell to reduce him to, no ‘ism’ to give him a lasting home (the Nabis were more of a brotherhood), no one specific style to make him recognizable, no pathology to explain his subject matter (500 nudes) or his drive (nearly 2000 works).

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

IBM says it will build a practical quantum supercomputer by 2029

Karmela Padavic-Callaghan in New Scientist:

In less than five years, we will have access to an error-free quantum supercomputer – so says IBM. The firm has presented a roadmap for building this machine, called Starling, slated to be available to researchers across academia and industry in 2029.

In less than five years, we will have access to an error-free quantum supercomputer – so says IBM. The firm has presented a roadmap for building this machine, called Starling, slated to be available to researchers across academia and industry in 2029.

“These are science dreams that became engineering,” says Jay Gambetta at IBM. He says that he and his colleagues have now developed all the pieces needed to make Starling work, and this makes them confident about their ambitious timeline. The new device will be housed in a data centre in New York, and Gambetta says that it could be useful to manufacturers of new chemicals and materials. Such computers are considered particularly suited to simulating materials at the quantum level.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.