James G. Harper and Philip W. Scher at Cabinet Magazine:

In January 1934, the eminent anthropologist Julius Lips sat in a small hotel room at the Hôtel des Nations in the Latin Quarter of Paris, staring down at a trunk full of cardboard-mounted photographs. It was about all he had with him, having fled Germany with no family, no means of support, and no clear conception of his future except the idea that he might make his way to the United States. The photographs in the trunk, collected over a decade and through an extensive scholarly and institutional network, were of artworks from around the world that depicted the figure of the European through non-Western eyes. Some wryly humorous, some outright insulting, these objects tell a different story than that which Europeans had told themselves during the age of colonialism. Lips intended his research to culminate in a groundbreaking book, the working title of which was “How the Black Man Looks at the White Man.”

Back in Germany, Julius Lips had been a star on the rise: appointed director of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in 1928 at the age of thirty-three, he was tenured as a senior faculty member at the University of Cologne just two years later. But with the rise of the Nazi party and Lips’s refusal to “coordinate” with the new regime, he was dismissed from his posts and his career came to a halt. His unwillingness to hand over the trunk full of photographs only further infuriated the authorities.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The rapidly escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran represents a clash of ambitions. Iran seeks to become a nuclear power, and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu longs to be remembered as the Israeli leader who categorically thwarted Iran’s nuclear program, which he views as an existential threat to Israel’s survival. Both dreams are as misguided as they are dangerous.

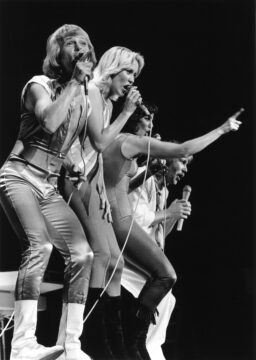

The rapidly escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran represents a clash of ambitions. Iran seeks to become a nuclear power, and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu longs to be remembered as the Israeli leader who categorically thwarted Iran’s nuclear program, which he views as an existential threat to Israel’s survival. Both dreams are as misguided as they are dangerous. There is probably not a second that goes by without an ABBA song being played somewhere in the world. A remix of “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” is pulsing through a club on a Mediterranean island, a Vietnamese grocery store is piping in “Happy New Year,” a Mexican radio station is playing the Spanish-language version of “Knowing Me, Knowing You.” Live performances, too, continue unabated, and not just in karaoke bars, or in stage productions of “

There is probably not a second that goes by without an ABBA song being played somewhere in the world. A remix of “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” is pulsing through a club on a Mediterranean island, a Vietnamese grocery store is piping in “Happy New Year,” a Mexican radio station is playing the Spanish-language version of “Knowing Me, Knowing You.” Live performances, too, continue unabated, and not just in karaoke bars, or in stage productions of “ T

T Harvard never wanted or expected this.

Harvard never wanted or expected this. For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or

For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or  W

W To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time.

To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time. Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue

Let’s be frank: It’s a somewhat presumptuous name for a magazine. Adopting it may have been akin to what philosophers refer to as a “speech act,” meant to call into being the very thing referred to. Largely absent from pre–Civil War political rhetoric, which more often spoke of “the union” or “the republic,” the word nation appeared five times in Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. Two years later, when the first issue  The best measure of serenity may be our distance from the self — getting far enough to dim the glare of ego and quiet the din of the mind, with all its ruminations and antagonisms, in order to see the world more clearly, in order to hear more clearly our own inner voice, the voice that only ever speak of love.

The best measure of serenity may be our distance from the self — getting far enough to dim the glare of ego and quiet the din of the mind, with all its ruminations and antagonisms, in order to see the world more clearly, in order to hear more clearly our own inner voice, the voice that only ever speak of love. When Jeanne Calment died at the age of 122, her

When Jeanne Calment died at the age of 122, her  I came to all

I came to all In matters of style

In matters of style The annual Berggruen Prize Essay Competition seeks to stimulate new thinking and innovative concepts while embracing cross-cultural perspectives across fields, disciplines, and geographies. By posing fundamental philosophical questions of significance for both contemporary life and for the future, the competition will serve as a complement to the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, which recognizes major lifetime achievements in advancing ideas that have shaped the world.

The annual Berggruen Prize Essay Competition seeks to stimulate new thinking and innovative concepts while embracing cross-cultural perspectives across fields, disciplines, and geographies. By posing fundamental philosophical questions of significance for both contemporary life and for the future, the competition will serve as a complement to the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, which recognizes major lifetime achievements in advancing ideas that have shaped the world. At the turn of the 20th century, the renowned mathematician David Hilbert had a grand ambition to bring a more rigorous, mathematical way of thinking into the world of physics. At the time, physicists were still plagued by debates about basic definitions — what is heat? how are molecules structured? — and Hilbert hoped that the formal logic of mathematics could provide guidance.

At the turn of the 20th century, the renowned mathematician David Hilbert had a grand ambition to bring a more rigorous, mathematical way of thinking into the world of physics. At the time, physicists were still plagued by debates about basic definitions — what is heat? how are molecules structured? — and Hilbert hoped that the formal logic of mathematics could provide guidance.