Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

How to escape the “dopamine crash loop” and rewire your curiosity

Anne-Laure Le Cunff at Big Think:

This is the double-edged sword of dopamine. On one hand, this neurotransmitter might be considered the engine of human achievement. On the other hand, it’s incredibly vulnerable to manipulation by modern technology and instant gratification culture.

This is the double-edged sword of dopamine. On one hand, this neurotransmitter might be considered the engine of human achievement. On the other hand, it’s incredibly vulnerable to manipulation by modern technology and instant gratification culture.

But once you understand how your reward system works, you can consciously redirect it toward the things that actually matter to you. Let’s explore the connection between slot machines, social media, and the secret to a more curious, fulfilling life.

Your brain’s reward system is a network of regions that releases dopamine in response to rewarding stimuli. Think of dopamine as your brain’s “want” signal. It doesn’t create pleasure so much as it creates the motivation to seek pleasure.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

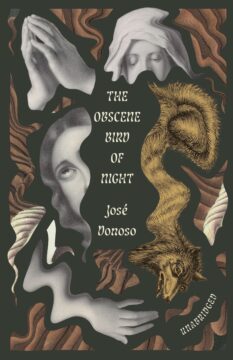

On José Donoso And His Translators

Angelo Hernandez Sias at n+1:

The Obscene Bird of Night is a cursed book. Its first translator, already a stand-in, disappeared from the project under mysterious circumstances. Its second translator, tapped to finish the job, never translated another book. Its third translator, some fifty years on, has been asked to revise rather than re-translate, grafting excised segments onto a nearly five-hundred page tome.1 Its author, who meant to knock it out in a few months, got lost in it for seven years, at the end of which he suffered his third bleeding ulcer, received an infected blood transfusion, had an allergic reaction to morphine, and nearly threw himself from a hospital window. Like that other seven-year endeavor, Ulysses, it has kept the professors busy, but the professors (the North American ones) have not kept it in print. It made Bolaño a lazy critic, it made Knopf the CIA, and it made your humble literary servant think that perhaps he should stick to serving ice cream. I’d have missed out. As the novel’s narrator puts it, “Servants accumulate the privileges of misery.”

The Obscene Bird of Night is a cursed book. Its first translator, already a stand-in, disappeared from the project under mysterious circumstances. Its second translator, tapped to finish the job, never translated another book. Its third translator, some fifty years on, has been asked to revise rather than re-translate, grafting excised segments onto a nearly five-hundred page tome.1 Its author, who meant to knock it out in a few months, got lost in it for seven years, at the end of which he suffered his third bleeding ulcer, received an infected blood transfusion, had an allergic reaction to morphine, and nearly threw himself from a hospital window. Like that other seven-year endeavor, Ulysses, it has kept the professors busy, but the professors (the North American ones) have not kept it in print. It made Bolaño a lazy critic, it made Knopf the CIA, and it made your humble literary servant think that perhaps he should stick to serving ice cream. I’d have missed out. As the novel’s narrator puts it, “Servants accumulate the privileges of misery.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ken Roth: Trump can be prosecuted for abetting genocide in Gaza

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Letters from Claude McKay

Claude McKay at the Paris Review:

My dear Langston

My dear Langston

I had the book alright and beg your forgiveness for not thanking and congratulating you too before. But for three months I’ve been going around with your letter in my pocket (that nice racy one about your party at [Carl] Van Vechten’s) with the intention of writing you a real letter. But I have been so worried and unsettled I could not settle down to the job. I picked up a hundred francs here, a dollar there, trying to live in a way you can’t imagine. With me, trying to live became a job, a problem. I moved from Juan-les-Pins to Cagnes from Cagnes to Nice from Nice to Menton and back again to Nice, wherever I heard of a cheap room I hunted it up. But you can live cheap when you have the teensiest bit of sure money coming to you. When you haven’t, it’s stupid to bother. When I came out of hospital I found a job as valet-butler to a civilised cracker doctor and his Russian wife. I stayed with them a month. The experience was so interesting I kept a diary of it. When I say civilized I mean it in the typical cracker sense. I couldn’t stay over the month and I stayed it out simply because I’d lose my 200 francs if I hadn’t. It gave me an insight into what the French “bonne a tout faire” has got to do. You work from 7–10 at night without any letting up.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I Asked ChatGPT What Would Happen If Billionaires Paid Taxes at the Same Rate as the Upper Middle Class

Jordan Rosenfeld at Go Banking Rates:

For starters, ChatGPT said that if billionaires paid taxes like the upper middle class, the government would bring in a lot more money — potentially hundreds of billions of dollars more every year. “That’s because most billionaires don’t make their money from salaries like upper-middle-class workers do. Instead, they grow their wealth through investments–stocks, real estate, and businesses–which are often taxed at much lower rates or not taxed at all until the assets are sold,” ChatGPT told me.

For starters, ChatGPT said that if billionaires paid taxes like the upper middle class, the government would bring in a lot more money — potentially hundreds of billions of dollars more every year. “That’s because most billionaires don’t make their money from salaries like upper-middle-class workers do. Instead, they grow their wealth through investments–stocks, real estate, and businesses–which are often taxed at much lower rates or not taxed at all until the assets are sold,” ChatGPT told me.

Billionaire income is largely derived from capital appreciation, not wages. In other words, they make money on their money through interest. And as of yet, the U.S. tax code doesn’t tax “unrealized capital gains” so until you sell your assets, you could amass millions in appreciation and not pay a dime on it, ChatGPT shared.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

For the Children

The rising hills, the slopes,

of statistics

lie before us,

the steep climb

of everything, going up,

up, as we all

go down.

In the next century

or the one beyond that,

they say,

are valleys, pastures,

we can meet there in peace

if we make it.

To climb these coming crests

one word to you, to

you and your children:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

by Gary Snyder

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

AI-Designed Drugs Can Now Target Previously ‘Undruggable’ Proteins in Cancer and Alzheimer’s

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Designing drugs is a bit like playing with Polly Pocket. The vintage toy is a plastic clam shell that contains a multi-bedroom house, a skating rink, a disco dance floor, and other fun scenarios. Kids snap tiny dolls into designated spots so they can spin them around or move them up and down on an elevator. To work, the fit between the doll and its spot has to be perfectly aligned.

Designing drugs is a bit like playing with Polly Pocket. The vintage toy is a plastic clam shell that contains a multi-bedroom house, a skating rink, a disco dance floor, and other fun scenarios. Kids snap tiny dolls into designated spots so they can spin them around or move them up and down on an elevator. To work, the fit between the doll and its spot has to be perfectly aligned.

Proteins and the drugs targeting them are like this. Each protein has an intricate and unique shape, with areas that grab other molecules to trigger physiological effects. Many of our most powerful drugs—from antibiotics to anti-cancer immunotherapies—are carefully engineered to snap onto proteins and alter their functions. Designing them takes months or years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Peter Beinart – “Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, July 29, 2025

A mathematician’s coming-of-age story

Ben Orlin at Math With Bad Drawings:

Every baby is born the same way (namely, as a baby).

Every baby is born the same way (namely, as a baby).

And every mathematician is born the same way, too: as a baby as a Platonist.

It usually begins something like this: What exactly are triangles? In a cosmos where no plane is perfectly flat, no segment perfectly straight, and no corner perfectly sharp, are Euclidean triangles in any sense “real”?

Yes, says the Platonist. Tangible? No. Physical? No. But the Platonist has tasted enough of math to know, in her bones, that math is more than just human whim. Math must, in some independent sense, exist. The Platonist believes (in the grand tradition of Seinfeld) that mathematical objects are real, and they’re spectacular.

Other philosophies may come later. Structuralists evolve, like birds from dinosaurs. Formalists are trained, like soldiers in boot camp. Intuitionists emerge, like neo-reactionaries from economic recessions.

But every mathematician begins in the same sweet swaddle of Platonism.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

One of the biggest microplastic pollution sources isn’t straws or grocery bags – it’s your tires

Boluwatife S. Olubusoye and James V Cizdziel in The Conversation:

Every few years, the tires on your car wear thin and need to be replaced. But where does that lost tire material go?

Every few years, the tires on your car wear thin and need to be replaced. But where does that lost tire material go?

The answer, unfortunately, is often waterways, where the tiny microplastic particles from the tires’ synthetic rubber carry several chemicals that can transfer into fish, crabs and perhaps even the people who eat them.

We are analytical and environmental chemists who are studying ways to remove those microplastics – and the toxic chemicals they carry – before they reach waterways and the aquatic organisms that live there.

Millions of metric tons of plastic waste enter the world’s oceans every year. In recent times, tire wear particles have been found to account for about 45% of all microplastics in both terrestrial and aquatic systems.

Tires shed tiny microplastics as they move over roadways. Rain washes those tire wear particles into ditches, where they flow into streams, lakes, rivers and oceans.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stephen Fry and Yuval Noah Harari discuss how to control AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Money Fight That Will Shape Europe’s Future

Carl Bildt at Project Syndicate:

Three urgent priorities are set to strain Europe’s public finances over the next few years. The first – and most obvious – is defense. The push to boost military spending is primarily a response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression, compounded by US President Donald Trump’s relentless criticism of America’s NATO allies. Together, these pressures have made strengthening Europe’s defense posture a strategic necessity.

Three urgent priorities are set to strain Europe’s public finances over the next few years. The first – and most obvious – is defense. The push to boost military spending is primarily a response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggression, compounded by US President Donald Trump’s relentless criticism of America’s NATO allies. Together, these pressures have made strengthening Europe’s defense posture a strategic necessity.

The second, and arguably more urgent, priority is to support Ukraine in its fight against Russia. If Ukraine’s defenses were to collapse, a revanchist Russia would likely go on a rampage. Ensuring that Ukraine can continue to defend itself will require European governments to go beyond their existing defense-spending commitments.

And lastly, there is the lengthy process of producing the European Union’s next multiyear budget, which will cover the period from 2028 to 2034.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

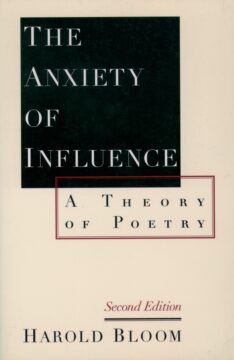

The Anxiety of Influence

Adam Phillips at Salmagundi:

In a piece written by the critic Kenneth Gross, an ex-student of Harold Bloom, we read that “Bloom was always alive to Blake’s way of joining visionary, esoteric wildness and blunt sceptical, satirical rage. He treasured Blake’s cheerful independence, his dark sense of humour, his willingness to think through for himself all ideas and traditions, his hatred of the mind’s capacity to accept and forge limitations for itself and others, and his ambition of ‘opening up the reader’s own buried capacity for imaginative self-liberation.’”

This is as good an account as any of the spirit and preoccupations of Bloom’s work; it being the singular, original, idiosyncratic independence and radical non-compliance of Blake’s vision that Bloom celebrated, and aspired to. (Bloom said in an interview that when he read Northrop Frye’s book on Blake, Fearful Symmetry, it was the best book he had ever read, and that after many readings he knew it by heart.) The Anxiety of Influence—at once a history of poetic tradition, and a story about the individual development of what Bloom called “strong poets”—was the book that first fully exemplified, or theorised, what Bloom, in Gross’s account, valued about Blake.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

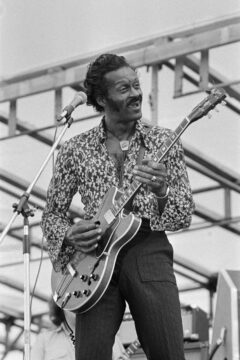

Chuck Berry’s ‘Maybellene’

Alex Abramovich at the LRB:

‘There are ten thousand freedoms,’ the late Joshua Clover once said, ‘but rock freedom is definitely set – in the first instance – in a car, when it’s late outside. It can be ecstatic, it can be boring, it can be adjectiveless freedom, but you have reached escape velocity, faster miles an hour, you have no particular place to go, and you have the radio on.’

‘There are ten thousand freedoms,’ the late Joshua Clover once said, ‘but rock freedom is definitely set – in the first instance – in a car, when it’s late outside. It can be ecstatic, it can be boring, it can be adjectiveless freedom, but you have reached escape velocity, faster miles an hour, you have no particular place to go, and you have the radio on.’

Chuck Berry’s ‘Maybellene’ recently turned seventy. Recorded on 21 May 1955 in a studio on the South Side of Chicago, it tells the story of a man chasing his girlfriend down the highway. He’s in a Ford V8, she’s driving a Cadillac. She’s cheating, the car’s overheating, he’s trying to catch her before she gets away for good. ‘Maybellene’ isn’t Chuck Berry’s best song but it was his first single. Without it there’d be no Bob Dylan. No rock and roll as we know it. It’s a miracle.

There’s a story about the song, too. The demo tape that Chuck Berry gave Leonard Chess included a slow blues, ‘Wee Wee Hours’, and a faster number that Berry called ‘Ida Mae’.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

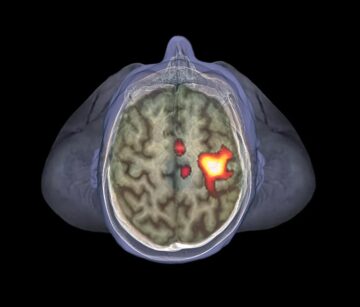

The brain fires up immune cells when sick people are nearby

Katie Kavanagh in Nature:

The brain activates front-line immune cells in response to the mere sight of a sick person, mimicking the body’s response to an actual infection, a study shows1. The results required the use of brain scans and blood tests, as well as less conventional technology: gaming kit. Study volunteers donned virtual reality (VR) headsets to view human avatars with rashes, coughs or other symptoms of illness — avoiding the need to expose volunteers to pathogens. The results illustrate the power of the brain “to predict what is going on [and] to select the proper response”, says study co-author Andrea Serino, a neuroscientist at the University Hospital of Lausanne, Switzerland.

The brain activates front-line immune cells in response to the mere sight of a sick person, mimicking the body’s response to an actual infection, a study shows1. The results required the use of brain scans and blood tests, as well as less conventional technology: gaming kit. Study volunteers donned virtual reality (VR) headsets to view human avatars with rashes, coughs or other symptoms of illness — avoiding the need to expose volunteers to pathogens. The results illustrate the power of the brain “to predict what is going on [and] to select the proper response”, says study co-author Andrea Serino, a neuroscientist at the University Hospital of Lausanne, Switzerland.

The immune system reacts promptly to infections, but it can’t always move fast enough to prevent serious illness. That means it would be useful for the body to realize that an infection is possible and mount a pre-emptive response. To study humans’ ability to anticipate a pathogen attack, Serino and his colleagues outfitted healthy volunteers with Google’s Oculus Rift headsets and showed them avatars that approached closer and closer, although the avatars never ‘touched’ the participants. Some avatars showed signs of having an infectious illness; others were controls that looked healthy.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Ali Akbar Natiq Designed Jamia Fatima Tul Zahra. Murree Road. Rawalpindi

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Inversion

trees dangle upside down from a sky

which is no longer sky

but mineral gem earth insulating us

from the various problems of birds

singing below singing below

a reminder of the past kept

in the folds of distance

as I walk through blue & discarded clouds

I examine tree canopy’s swish

a froth situating my ankles

these shocks of green

everywhere everywhere flesh

of leaves & stalks pertinent

to my arms & legs & face

an almost-substitute for people

(remembering when people

touched each other’s bodies)

branches are capillaries & how like skin

to be this dry & forgotten

like when you were here last

& I rubbed rose oil

into the difficult geometry

of your scars

by Carolyn Wilsey

from Pank Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Chuck Berry – Maybellene

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, July 28, 2025

When Fact-Checking Meant Something

Susan Choi in The Yale Review:

What i always say is that I wasn’t a very good checker. I don’t mean I made mistakes—mistakes being, in fact-checking, failing to catch someone else’s mistakes. I mean that the things I checked weren’t serious or difficult, that generally, the bar was pretty low. This was at Tina Brown’s New Yorker in the mid-1990s, a time when the magazine was trying to raise its own heart rate. The idea was to make headlines, not just cultural history. But when we had a piece whose publication might result in a lawsuit or an international incident, or a person’s vindication or ruination, or a significant and unanticipated paradigm shift on a matter of collectively agreed-upon importance, such as the Holocaust or Shakespeare, I wasn’t the first checker anyone thought of. My boss—a brilliant, kind, and fair man I still count as a friend—tended to pitch me softballs, an expression I’ve never understood because I didn’t check sports articles either, being equally ignorant about every sport. I tended to check culture pieces: reconsiderations of, say, Maria Callas, for which there was no “peg”—an occasion in the real world that dictated when it should publish—beyond the opera-loving author’s strong feeling that Callas was owed some attention. This was the sort of piece that might long remain in unscheduled limbo, allowing me to bone up on Callas, about whom I knew nothing.

What i always say is that I wasn’t a very good checker. I don’t mean I made mistakes—mistakes being, in fact-checking, failing to catch someone else’s mistakes. I mean that the things I checked weren’t serious or difficult, that generally, the bar was pretty low. This was at Tina Brown’s New Yorker in the mid-1990s, a time when the magazine was trying to raise its own heart rate. The idea was to make headlines, not just cultural history. But when we had a piece whose publication might result in a lawsuit or an international incident, or a person’s vindication or ruination, or a significant and unanticipated paradigm shift on a matter of collectively agreed-upon importance, such as the Holocaust or Shakespeare, I wasn’t the first checker anyone thought of. My boss—a brilliant, kind, and fair man I still count as a friend—tended to pitch me softballs, an expression I’ve never understood because I didn’t check sports articles either, being equally ignorant about every sport. I tended to check culture pieces: reconsiderations of, say, Maria Callas, for which there was no “peg”—an occasion in the real world that dictated when it should publish—beyond the opera-loving author’s strong feeling that Callas was owed some attention. This was the sort of piece that might long remain in unscheduled limbo, allowing me to bone up on Callas, about whom I knew nothing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.