Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Variants of Nationalism, Some Poisonous and Some Benign

Pranab Bardhan at his Substack:

In thinking about the positive basis of nationalism for post-colonial India, Tagore and Gandhi found the nation-state of European history—characterized by a singular social, usually ethnic or linguistic, homogenizing principle, militarized borders and mobilization against ‘enemies’ both external and internal—unacceptable and unsuitable for India’s diverse and heterogeneous society. Their idea of India was not monolithic state-centric, but pluralistic and community- or society-centric.

In thinking about the positive basis of nationalism for post-colonial India, Tagore and Gandhi found the nation-state of European history—characterized by a singular social, usually ethnic or linguistic, homogenizing principle, militarized borders and mobilization against ‘enemies’ both external and internal—unacceptable and unsuitable for India’s diverse and heterogeneous society. Their idea of India was not monolithic state-centric, but pluralistic and community- or society-centric.

By the way, the singular social homogenizing principle mentioned above is not just western, it is also one of the basic tenets of Chinese civilization. The sinologist W.J.F Jenner in his book The Tyranny of History describes this basic tenet as ‘that uniformity is inherently desirable, that there should be only one empire, one culture, one script, one tradition’. In contrast, India, particularly in the historical perspective of Tagore, Nehru and their followers, has celebrated the diversity of Indian civilization. The current ruling cultural-political dispensation of RSS-BJP in India wants to displace that idea of India with the homogenizing principle of a Hindu-supremacist nation-state characterized by a ‘one nation, one everything’ motto. Their earlier ideological leaders (particularly Savarkar and Golwalkar) had expressed open admiration for the ‘efficient’ Nazi system of mobilizing and organizing the German nation.

The European scholar of nationalism who has shown the most sensitivity to the socio-cultural particularities in the construction or ‘imagination’ of national consciousness in different parts of the world was Benedict Anderson.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Penrose And Puzzles

Steven Shapin at the LRB:

Roger Penrose liked puzzles. In the 1950s, inspired by a catalogue of prints made by the paradoxical Dutch artist M.C. Escher, the young Penrose and his psychiatrist-geneticist father, Lionel, set out to produce drawings of ‘impossible objects’. Pictorial conventions cue us to perceive two-dimensional drawings as representations of three-dimensional things, but these conventions can also be used to deceive – for example, to depict things that could not exist in three dimensions. One of these objects became known as the ‘Penrose triangle’.

The Penroses were a family of puzzlers. Father and sons amused themselves by constructing polyhedra out of wood and cardboard that could be taken apart and put together in interesting ways. Everyone played chess: Lionel set puzzles and his wife, Margaret, like him a qualified physician, was a keen player; Oliver Penrose, Roger’s older brother, is a physicist and a proficient amateur player; and his younger brother, Jonathan, was a grandmaster and ten times British chess champion. But there was much more to Roger’s puzzling than this.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

Barn, with Weather

The barn stands at the field’s edge

facing nothing. Not the house,

long gone, nor the road, which curves

out of sight. Only the open, vast

democracy of stalk and wind. Its

paint is a ghostly suggestion of white

that clings to the grain like an afterimage

of snow; its boards have split and warped,

like pages of a book left open in the rain.

The sky today appears in gradients:

smoke-blue, salt-blue, ink soaked in milk,

a ceiling coming loose at the seams

and streaming light that seems reluctant.

There’s a certain correctness to how the

structure weathers: collapse is not an event

but a series of small, careful concessions.

This is how some things leave themselves—

slowly, with dignity, a long slog in

time and sun. Meanwhile, the barn does

not resist being seen. It stands where put,

neither proud nor ashamed, only exact.

by James Gonda

from Rattle Magazine

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

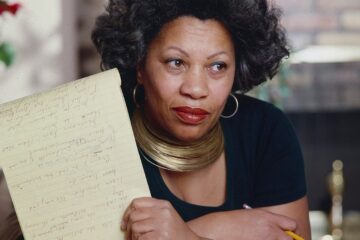

Notes From Ms. Morrison

Dana Williams in Slate:

I first interviewed Toni Morrison about her work as a book editor in September 2005, in her office at Princeton. Though our meeting was scheduled for late afternoon, I took an early train from Washington to make sure I could situate myself in West College—which would be renamed Morrison Hall in 2017—while I rehearsed my carefully crafted questions. I was struck by the quiet gravity of the building and its hallways: sunlight slanting through stately windows, the scent of old books and weathered wood lingering in the air. The fact that I was about to sit across from a literary giant—celebrated worldwide for her novels yet virtually unknown for her groundbreaking work as an editor at Random House—was not lost on me.

I first interviewed Toni Morrison about her work as a book editor in September 2005, in her office at Princeton. Though our meeting was scheduled for late afternoon, I took an early train from Washington to make sure I could situate myself in West College—which would be renamed Morrison Hall in 2017—while I rehearsed my carefully crafted questions. I was struck by the quiet gravity of the building and its hallways: sunlight slanting through stately windows, the scent of old books and weathered wood lingering in the air. The fact that I was about to sit across from a literary giant—celebrated worldwide for her novels yet virtually unknown for her groundbreaking work as an editor at Random House—was not lost on me.

My anxiousness reminded me that I had often wondered what it must have been like for authors to have the Toni Morrison as their editor. When the writer John A. McCluskey Jr. first met Morrison in 1971, she had published only The Bluest Eye. McCluskey, not yet 30 years old, saw her not as the Pulitzer Prize–winning Nobel laureate she would become, but as a fellow Ohio writer looking to make her mark as an editor. She was also, he discovered two years later, the kind of person who made a fuss when she learned that McCluskey’s wife and son were in the car waiting while they had their first author-editor meeting at the Random House offices on East 50th Street to discuss his first novel, Look What They Done to My Song. Whatever else was on her schedule would have to wait. She wanted to greet Audrey and Malik. It was the least she could do since they had joined McCluskey for the drive from the Midwest to Manhattan.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Crazy Ants Lead the Way for Swarm Intelligence, Helping Colonies Plan Complex Tasks

Jenny Lehmann in Discover:

Social insects like bees and ants have long impressed scientists with their ability to achieve remarkable feats, such as constructing towering nests and navigating complex environments. But how they manage this, especially with brains smaller than a poppy seed, continues to fascinate researchers. The secret, it turns out, isn’t in the individual — it’s in the group.

Social insects like bees and ants have long impressed scientists with their ability to achieve remarkable feats, such as constructing towering nests and navigating complex environments. But how they manage this, especially with brains smaller than a poppy seed, continues to fascinate researchers. The secret, it turns out, isn’t in the individual — it’s in the group.

A recent study from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel took a closer look at how ant colonies use “swarm intelligence” — a type of collective behavior where simple individuals work together to solve complex problems. The team was inspired by something that looked a lot like planning: ants clearing obstacles in advance of incoming food. “This is the first documented case of ants showing such forward-looking behavior during cooperative transport,” said study co-author Ehud Fonio in a press release.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, June 18, 2025

3 Quarks Daily Is Looking For New Columnists, DEADLINE Soon

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

Here’s your chance to say what you want to the large number of highly educated readers that make up 3QD’s international audience. Several of our regular columnists have had to cut back or even completely quit their columns for 3QD because of other personal and professional commitments and so we are looking for a few new voices. We do not pay, but it is a good chance to draw attention to subjects you are interested in, and to get feedback from us and from our readers.

We would certainly love for our pool of writers to reflect the diversity of our readers in every way, including gender, age, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, etc., and we encourage people of all kinds to apply. And we like unusual voices and varied viewpoints. So please send us something. What have you got to lose? Click on “Read more” below…

NEW POSTS BELOW

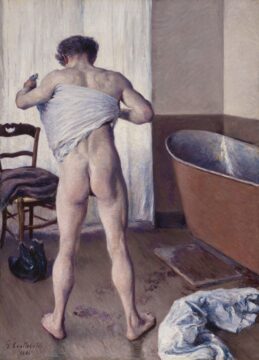

Men in the off hours

Fernanda Eberstadt at the European Review of Books:

Some years ago, I saw a painting that knocked my sense of the sexes sideways. It was an 1884 work by an Impressionist named Gustave Caillebotte of a nude figure emerging from the bath — the same trope that Degas or Bonnard so often employ because it allows you to observe a woman’s naked body in motion, absorbed in a private ritual replete with sensual pleasure.

Some years ago, I saw a painting that knocked my sense of the sexes sideways. It was an 1884 work by an Impressionist named Gustave Caillebotte of a nude figure emerging from the bath — the same trope that Degas or Bonnard so often employ because it allows you to observe a woman’s naked body in motion, absorbed in a private ritual replete with sensual pleasure.

Except that the nude that Caillebotte is presenting for our delectation is male, and this gender-switch totally upends our preconceptions about masculine power and prerogatives, about who gets to look at whom doing what.

Homme au Bain’s model is young, sturdy, athletic-looking. He has his back to us. He has just stepped out of the tub and is towelling himself dry; his large muscular buttocks are ruddy, seem chafed either from the steamy water or the towelling. The painter draws our eye to the shadowy violet-blue crease just north of the young man’s bottom, and between his legs we spy the dark hanging globe of his scrotum. The model’s fuzzy head is bent down, his gaze apparently fixed on the wet floor.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

At Secret Math Meeting, Researchers Struggle to Outsmart AI

Lyndie Chiou at Scientific American:

On a weekend in mid-May, a clandestine mathematical conclave convened. Thirty of the world’s most renowned mathematicians traveled to Berkeley, Calif., with some coming from as far away as the U.K. The group’s members faced off in a showdown with a “reasoning” chatbot that was tasked with solving problems they had devised to test its mathematical mettle. After throwing professor-level questions at the bot for two days, the researchers were stunned to discover it was capable of answering some of the world’s hardest solvable problems. “I have colleagues who literally said these models are approaching mathematical genius,” says Ken Ono, a mathematician at the University of Virginia and a leader and judge at the meeting.

On a weekend in mid-May, a clandestine mathematical conclave convened. Thirty of the world’s most renowned mathematicians traveled to Berkeley, Calif., with some coming from as far away as the U.K. The group’s members faced off in a showdown with a “reasoning” chatbot that was tasked with solving problems they had devised to test its mathematical mettle. After throwing professor-level questions at the bot for two days, the researchers were stunned to discover it was capable of answering some of the world’s hardest solvable problems. “I have colleagues who literally said these models are approaching mathematical genius,” says Ken Ono, a mathematician at the University of Virginia and a leader and judge at the meeting.

The chatbot in question is powered by o4-mini, a so-called reasoning large language model (LLM). It was trained by OpenAI to be capable of making highly intricate deductions. Google’s equivalent, Gemini 2.5 Flash, has similar abilities.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Bootsy Collins on Funk Legacy & Songwriting

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Terence Tao: Hardest Problems in Mathematics, Physics & the Future of AI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Looking Back at the White Man

James G. Harper and Philip W. Scher at Cabinet Magazine:

In January 1934, the eminent anthropologist Julius Lips sat in a small hotel room at the Hôtel des Nations in the Latin Quarter of Paris, staring down at a trunk full of cardboard-mounted photographs. It was about all he had with him, having fled Germany with no family, no means of support, and no clear conception of his future except the idea that he might make his way to the United States. The photographs in the trunk, collected over a decade and through an extensive scholarly and institutional network, were of artworks from around the world that depicted the figure of the European through non-Western eyes. Some wryly humorous, some outright insulting, these objects tell a different story than that which Europeans had told themselves during the age of colonialism. Lips intended his research to culminate in a groundbreaking book, the working title of which was “How the Black Man Looks at the White Man.”

Back in Germany, Julius Lips had been a star on the rise: appointed director of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in 1928 at the age of thirty-three, he was tenured as a senior faculty member at the University of Cologne just two years later. But with the rise of the Nazi party and Lips’s refusal to “coordinate” with the new regime, he was dismissed from his posts and his career came to a halt. His unwillingness to hand over the trunk full of photographs only further infuriated the authorities.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Israel’s War of Grand Ambition

Shlomo Ben-Ami at Project Syndicate:

The rapidly escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran represents a clash of ambitions. Iran seeks to become a nuclear power, and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu longs to be remembered as the Israeli leader who categorically thwarted Iran’s nuclear program, which he views as an existential threat to Israel’s survival. Both dreams are as misguided as they are dangerous.

The rapidly escalating military conflict between Israel and Iran represents a clash of ambitions. Iran seeks to become a nuclear power, and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu longs to be remembered as the Israeli leader who categorically thwarted Iran’s nuclear program, which he views as an existential threat to Israel’s survival. Both dreams are as misguided as they are dangerous.

Iran’s nuclear ambitions have always been driven primarily by the goal of securing the regime’s survival, not annihilating Israel, which is far more likely to be destroyed at the end of a long war of attrition than under a mushroom cloud. But Israel cannot afford to treat Iran’s threats of nuclear Armageddon as mere bloviating, particularly after Hamas’s October 7 terrorist attack, which triggered Israel’s long, brutal, and ongoing offensive against the Iranian proxy in Gaza. It is not wrong to fear a nuclear Iran.

But Netanyahu is a key reason why Iran’s nuclear program is as far along as it is.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

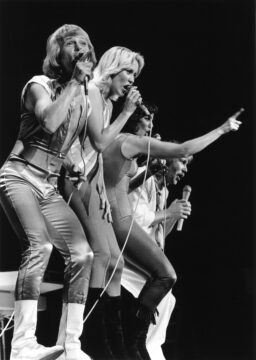

The World That ABBA Made

Mitch Therieau at The New Yorker:

There is probably not a second that goes by without an ABBA song being played somewhere in the world. A remix of “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” is pulsing through a club on a Mediterranean island, a Vietnamese grocery store is piping in “Happy New Year,” a Mexican radio station is playing the Spanish-language version of “Knowing Me, Knowing You.” Live performances, too, continue unabated, and not just in karaoke bars, or in stage productions of “Mamma Mia!” Maybe it is morning in Kawasaki, Japan, and a tribute band is performing for thirty people in a public square, or evening in Johannesburg, where a different tribute act plays to a sold-out theatre. (The group Björn Again, the best known of these reënactors, claims to have been summoned to perform for an enthusiastic Vladimir Putin; the Kremlin denies this.) In London, you can see and hear the real thing—or, at least, life-size holograms of its members, affectionately called ABBAtars, fronting a live band in a purpose-built arena.

There is probably not a second that goes by without an ABBA song being played somewhere in the world. A remix of “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)” is pulsing through a club on a Mediterranean island, a Vietnamese grocery store is piping in “Happy New Year,” a Mexican radio station is playing the Spanish-language version of “Knowing Me, Knowing You.” Live performances, too, continue unabated, and not just in karaoke bars, or in stage productions of “Mamma Mia!” Maybe it is morning in Kawasaki, Japan, and a tribute band is performing for thirty people in a public square, or evening in Johannesburg, where a different tribute act plays to a sold-out theatre. (The group Björn Again, the best known of these reënactors, claims to have been summoned to perform for an enthusiastic Vladimir Putin; the Kremlin denies this.) In London, you can see and hear the real thing—or, at least, life-size holograms of its members, affectionately called ABBAtars, fronting a live band in a purpose-built arena.

Such is the afterlife in pop Valhalla. ABBA, made up of the songwriter-producers Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson and the singers Agnetha Fältskog and Anni-Frid Lyngstad, is bigger today than it ever was during the group’s active years, between 1972 and 1982—a dense stretch that saw the two couples that made up the band splitting up but continuing to make music together.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

Obligation #25 (Transaction)

I cross my legs -I- brush

my clavicle / I pitch my

laugh – I laugh – I look

away / I smile – I lock my

weight in my right

hip – I pop tongue – I smear lip

gloss – I slip / on heels – I eat when I

can – I am not / always fixed – I am

Trying always new

movements – I move to a

city that swells / in a river

valley – I still see crows / I loved

a man who was made of more

want than reliability

– I love him – I undress myself

for weather / wilding its

way through the trees – I pull

cards now too – I can see there

from here – do I mention economy

at this point? I cost I want & it costs

to want this.

By Jzl Jmz

from Split This Rock

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

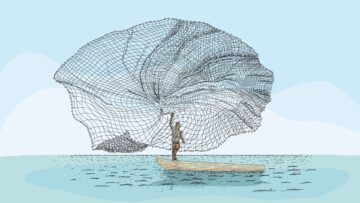

Uncovering the Exposome: An Emerging Field Casts a Wide Net

Emma Merchant in Undark Magazine:

The lab buildings of Long Island’s renowned Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have hosted researchers responsible for some of the most consequential scientific leaps in human genetics and disease. In the last 60 years, eight of the lab’s scientists have earned Nobel Prizes, including for work on how viruses replicate, on chromosome structure, and how edited genes can cause disease.

The lab buildings of Long Island’s renowned Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have hosted researchers responsible for some of the most consequential scientific leaps in human genetics and disease. In the last 60 years, eight of the lab’s scientists have earned Nobel Prizes, including for work on how viruses replicate, on chromosome structure, and how edited genes can cause disease.

That setting felt auspicious when nearly two-dozen people, most of them researchers, gathered at a conference center about 5 miles from the main campus in December 2023 to lay out the definition for a budding scientific discipline nearly two decades in the making. The work aims to understand human health outcomes by cataloguing the tens of thousands of chemicals and conditions a person is exposed to over the course of their life and determine how those interactions affect their unique biology, a concept referred to as the exposome.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

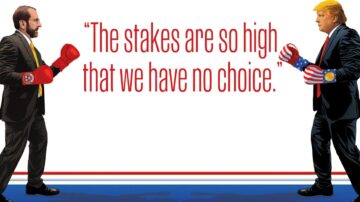

The Standoff: Harvard’s Future in the Balance

From Harvard Magazine:

Harvard never wanted or expected this. University leaders had spent the spring in conversation with the Trump administration, which threatened to withdraw federal funding if charges of antisemitism on campus were not addressed. But when a letter arrived on April 11 with a list of sweeping demands—effectively giving the government control of Harvard’s hiring, admissions, and even the makeup of academic departments—negotiations came to a halt. In an interview with NBC later that month, President Alan M. Garber explained the decision: “The stakes are so high that we have no choice” but to fight.

Harvard never wanted or expected this. University leaders had spent the spring in conversation with the Trump administration, which threatened to withdraw federal funding if charges of antisemitism on campus were not addressed. But when a letter arrived on April 11 with a list of sweeping demands—effectively giving the government control of Harvard’s hiring, admissions, and even the makeup of academic departments—negotiations came to a halt. In an interview with NBC later that month, President Alan M. Garber explained the decision: “The stakes are so high that we have no choice” but to fight.

So launched the extraordinary battle that is playing out in federal court, in op-ed pages, on social media, and sometimes in the streets. The government has targeted Harvard’s research funding, endowment, and ability to enroll international students. Harvard has filed two federal lawsuits, seeking to stop the government’s actions on the grounds of free speech violations and administrative overreach. And the University’s stand against the Trump administration has made Harvard a symbol in the public eye—a stand-in for higher education, globalization, and the government’s traditional role in advancing science and innovation.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A common parenting practice may be hindering teen development

Sujata Gupta in ScienceNews:

For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or walk or bike to school alone compared with previous generations, psychologist Peter Gray and colleagues noted in a September 2023 review in the Journal of Pediatrics. Other research shows that parents report increasing discomfort with letting their kids engage in risky, unsupervised play.

For years, researchers and policymakers have been sounding the alarm about the limited opportunities children and teenagers have to play and explore without adults around. For instance, children across much of the Western world are less likely to hold part-time jobs or walk or bike to school alone compared with previous generations, psychologist Peter Gray and colleagues noted in a September 2023 review in the Journal of Pediatrics. Other research shows that parents report increasing discomfort with letting their kids engage in risky, unsupervised play.

That loss of freedom coincides with a decades-long uptick in teen mental health problems. But showing that one causes the other has proven difficult because of all the other recent changes to childhood, such as technology use, researchers say. But it’s clear that squelching childhood independence undermines normal development, including a teenager’s innate need for close peers and intimate partners, says Gray, of Boston College. “It’s absolutely no surprise to me that we are seeing these dramatic rises in anxiety, depression, even suicide among teenagers.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, June 17, 2025

How Pakistan fell in love with sushi

Sanam Maher in The Guardian:

When the 17-storey Avari Towers opened in Karachi in April 1985, it was the tallest hotel in the city. “It felt otherworldly,” said one chef who worked there as a teenager. “It was there that I saw a swimming pool for the first time,” he remembered, “and swimsuits.” By December 1986, this $32m building had another novelty to offer – Fujiyama, a Japanese restaurant at its summit. There had been no advertisements for Fujiyama, and for its first six weeks, the only way to get in was with an invitation; these began to land in the homes and offices of the city’s bankers, businessmen, doctors and other members of Karachi’s elite. By the new year, the restaurant was so busy it had waiting lists. There were now two kinds of people in the city of 6 million: those who had tried sushi and those who had not.

When the 17-storey Avari Towers opened in Karachi in April 1985, it was the tallest hotel in the city. “It felt otherworldly,” said one chef who worked there as a teenager. “It was there that I saw a swimming pool for the first time,” he remembered, “and swimsuits.” By December 1986, this $32m building had another novelty to offer – Fujiyama, a Japanese restaurant at its summit. There had been no advertisements for Fujiyama, and for its first six weeks, the only way to get in was with an invitation; these began to land in the homes and offices of the city’s bankers, businessmen, doctors and other members of Karachi’s elite. By the new year, the restaurant was so busy it had waiting lists. There were now two kinds of people in the city of 6 million: those who had tried sushi and those who had not.

In the late 80s, a Japanese restaurant like Fujiyama was an expensive proposition: foreign chefs had to be hired, staff trained, and ingredients, from wasabi to rice, constantly imported. Sushi – raw fish – in a country where daal roti is a staple and vegetables are often cooked down until they lose their crunch: who would take such a risk? And yet, somehow, it paid off. Fujiyama was the first place to serve Japanese cuisine in Pakistan, and it was where many Pakistanis encountered sushi for the first time.

Today, you can finish your day of fasting during Ramadan at a sushi buffet or host a wedding reception for a small (by Pakistani standards) gathering of 100 or more at a Japanese restaurant. When restaurants closed during the pandemic, waiters zipped across the city on motorbikes to deliver sushi.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

An immersive ‘flow state’ isn’t only accessible to great artists and athletes. You can find your flow too. Here’s how

Julia F Christensen at Aeon:

To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time.

To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time.

Modern neuroscience distinguishes between two mental states: one of striving, where a surge of dopamine keeps us laser-focused on external goals like winning, perfection or achievement – and another of serene presence, where we hover in the moment, simply being. In this latter state, our neural chemistry shifts; endogenous opioids and endocannabinoids fill the brain, bringing feelings of deep satisfaction, fulfilment and joy in the now.

Motivation psychologists distinguish these two states as extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for what we’re doing. The former takes hard work and discipline to keep us going. The latter propels us forward, as by magic: flow. Research even shows that those more prone to enter the flow state might have lower risk of mental health problems and cardiovascular disease.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.