Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Neither Mamdani nor Bernie is a Democratic Socialist

Pranab Bardhan at his own Substack:

Zorhan Mamdani, the presumed front-runner in the New York mayoral race, calls himself a democratic socialist (which scares Wall Street). So did US senator Bernie Sanders in his earlier election campaigns. Historically, a socialist is usually associated with advocacy of ownership or control of means of production primarily resting with the state or other non-private entities (like cooperatives or worker-owned enterprises). I have not heard either Mamdani or Sanders being associated with the advocacy of any such transformation of most of the means of production in the US. I think they are simply European-style social democrats, who would keep the mode of production essentially capitalist (with some possible light modifications) but with a somewhat greater role of the state in education, health and other welfare services (which, of course, may require higher taxes on the rich).

Zorhan Mamdani, the presumed front-runner in the New York mayoral race, calls himself a democratic socialist (which scares Wall Street). So did US senator Bernie Sanders in his earlier election campaigns. Historically, a socialist is usually associated with advocacy of ownership or control of means of production primarily resting with the state or other non-private entities (like cooperatives or worker-owned enterprises). I have not heard either Mamdani or Sanders being associated with the advocacy of any such transformation of most of the means of production in the US. I think they are simply European-style social democrats, who would keep the mode of production essentially capitalist (with some possible light modifications) but with a somewhat greater role of the state in education, health and other welfare services (which, of course, may require higher taxes on the rich).

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In Conversation: Takashi Murakami

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Marie NDiaye: The Art of Fiction

Madeline Schwartz in The Paris Review:

Marie NDiaye’s books are often violent, but the violence takes highly particular forms. A person might find herself suddenly called a different name by everyone around her, like Fanny in Among Family (1990, translation 1997), or pregnant with a strange creature, as does Nadia in My Heart Hemmed In (2007, 2017). A lawyer might try to comprehend an act of infanticide; a woman working in a hotel might find herself in a sexual relationship with her boss, who has their encounters filmed. The shocking nature of such scenarios is offset by NDiaye’s prose, precise and formal, with a restraint that adds to her work’s unnerving quality: a placidity where one might expect horror. Claire Denis, with whom NDiaye wrote the screenplay for the film White Material (2009), has described her work as “unbearably sweet.”

Marie NDiaye’s books are often violent, but the violence takes highly particular forms. A person might find herself suddenly called a different name by everyone around her, like Fanny in Among Family (1990, translation 1997), or pregnant with a strange creature, as does Nadia in My Heart Hemmed In (2007, 2017). A lawyer might try to comprehend an act of infanticide; a woman working in a hotel might find herself in a sexual relationship with her boss, who has their encounters filmed. The shocking nature of such scenarios is offset by NDiaye’s prose, precise and formal, with a restraint that adds to her work’s unnerving quality: a placidity where one might expect horror. Claire Denis, with whom NDiaye wrote the screenplay for the film White Material (2009), has described her work as “unbearably sweet.”

In person, NDiaye is warm and gracious. She likes talking about babies, dinner parties, her friends’ books; she often wanted to know what I was reading, and to discuss movies she enjoyed, like Anatomy of a Fall and Mulholland Drive.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The World’s Richest Woman Has Opened a Medical School

Alice Park in Time Magazine:

On July 14, 48 students walked through the doors of the Alice L. Walton School of Medicine in Bentonville, Ark. to become its inaugural class. Some came from neighboring cities, others from urban centers in Michigan and New York. Almost all had a choice in where they could become doctors but took a chance on the new school because of its unique approach to rethinking medical education.

On July 14, 48 students walked through the doors of the Alice L. Walton School of Medicine in Bentonville, Ark. to become its inaugural class. Some came from neighboring cities, others from urban centers in Michigan and New York. Almost all had a choice in where they could become doctors but took a chance on the new school because of its unique approach to rethinking medical education.

Named after its founder—the world’s richest woman and an heir to the Walmart fortune—the school will train students over the next four years in a radically different way from the method most traditional medical schools use. And that’s the point. Instead of drilling young physicians to chase symptom after symptom and perform test after test, Alice Walton wants her school’s graduates to keep patients healthy by practicing something that most doctors today don’t prioritize: preventive medicine and whole-health principles, which involve caring for (and not just treating) the entire person and all of the factors—from their mental health to their living conditions and lifestyle choices—that contribute to wellbeing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Takashi Murakami In Conversation

Ed Schad interviews Takashi Murakami at The Brooklyn Rail:

Rail: We have spoken in the past of the status that a copy has in Japan, that, for instance, it is not unusual or out of place to see a copy of a national treasure standing in for an original work in a museum. Practically, most treasures are too fragile and too old to be on continuous view, but it is also more than that, more like the copy can transmit what the original is meant to transmit. This bothers us in the West, but less so in Japan. We have also spoken of a copy as a way of both affirming and breaking from a teacher. Your idea of a person vicariously reaching back to Matabei through your work seems in this vein.

Rail: We have spoken in the past of the status that a copy has in Japan, that, for instance, it is not unusual or out of place to see a copy of a national treasure standing in for an original work in a museum. Practically, most treasures are too fragile and too old to be on continuous view, but it is also more than that, more like the copy can transmit what the original is meant to transmit. This bothers us in the West, but less so in Japan. We have also spoken of a copy as a way of both affirming and breaking from a teacher. Your idea of a person vicariously reaching back to Matabei through your work seems in this vein.

Murakami: Matabei captured all the details of people’s different jobs during a moment in the city of Kyoto, the landscape of the town, even more details than have been recorded in writing. So it really was just like I was using someone else’s genius to boost my work. It is difficult to do a copy of old works like these because so much of the original tints and paintings have rubbed off and a lot of the details are missing. If you fill in too many details or imitate too many of the missing lines, then it seems to become your own work and it has less to do with the older artist. However, two to three years ago I started to use AI to recreate those details more faithfully and get much closer to the older artist’s work. This use of AI to fill in the details of an older work made it possible later for me to work with Hiroshige’s prints when the Brooklyn Museum asked me.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday Poem

After Babel

What moved the men of Shinar

to build with brick and slime

their storied tower?

Was it a name

that kept them unified?

And why should God

destroy this unity

scattering them one by one

across the world?

I’ve never mastered

another tongue

always wondering

what was the language that we lost

the Ur-Sprache,

the babble we once shared

and whether it reappears unwittingly

in a mother’s lulling of a child,

the dialects of love,

our gestures when another suffers pain,

the will to give.

These are the bricks

we’ve always used to build

not only towers and walls

but simple, open places where we can live and breathe

and may still do.

by Michael Jackson

from Dead Reckoning

Auckland University Press, 2006

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

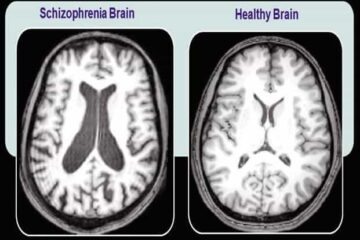

Mary Had Schizophrenia—Then Suddenly She Didn’t

Rachel Aviv at The New Yorker:

Karl Jaspers, the German psychiatrist and philosopher, has described what he calls the “delusional atmosphere,” a profound alteration in the way certain people experience the world. “There is some change which envelops everything with a subtle, pervasive and strangely uncertain light,” he wrote. People in this state search for a story that explains why everything suddenly feels uncanny and ominous. The “vagueness of content must be unbearable,” he wrote. “To reach some definite idea at last is like being relieved from some enormous burden.”

Karl Jaspers, the German psychiatrist and philosopher, has described what he calls the “delusional atmosphere,” a profound alteration in the way certain people experience the world. “There is some change which envelops everything with a subtle, pervasive and strangely uncertain light,” he wrote. People in this state search for a story that explains why everything suddenly feels uncanny and ominous. The “vagueness of content must be unbearable,” he wrote. “To reach some definite idea at last is like being relieved from some enormous burden.”

Mary had landed on a story that overwrote the reality of her daughters’ lives, but they also recognized in it a kind of emotional logic. Mary had been pressured to marry Chris, in an arranged match, and, when they settled in America, he had traditional ideas about a woman’s role and restricted her freedom to pursue her career. Christine and Angie came to feel that their mother’s delusions—that her former colleagues would free her from marriage and she’d be restored to her place in the medical community—were “a way of explaining how she ended up trapped in this position,” Christine said. “We theorized that psychosis was almost a reasonable response.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday, July 22, 2025

How TikTok is Transforming the English Language

Adam Aleksic at Literary Hub:

It seems as though everything happens faster on the internet. Each week brings a dizzying parade of new memes, fads, and slang words that evaporate as quickly as they materialize. It can be hard to keep up with the latest references unless you’re spending hours a day catching up on social media trends.

It seems as though everything happens faster on the internet. Each week brings a dizzying parade of new memes, fads, and slang words that evaporate as quickly as they materialize. It can be hard to keep up with the latest references unless you’re spending hours a day catching up on social media trends.

Of course, it wasn’t always like this: Look at Middle English six hundred years ago. Language was far more insular. Each city and region had its own, different dialect, to a point where there can scarcely be any discussion of a uniform “English” language as we understand it today. The only reason to adopt a new word was that it helped you better communicate with your fellow townspeople, so of course change came about more slowly.

Then England centralized, and the dialects of London and the East Midlands became the basis of what we now think of as Standard English. It was as if a switch had flipped: The upper class suddenly had a set vocabulary they could point to as “correct,” meaning that all other dialects became “incorrect.” By the 1750s, the word “slang” emerged as a catchall term to describe the nonstandard words used by the lower classes.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How Distillation Makes AI Models Smaller and Cheaper

Amos Zeeberg in Quanta:

The Chinese AI company DeepSeek released a chatbot earlier this year called R1, which drew a huge amount of attention. Most of it focused on the fact(opens a new tab) that a relatively small and unknown company said it had built a chatbot that rivaled the performance of those from the world’s most famous AI companies, but using a fraction of the computer power and cost. As a result, the stocks of many Western tech companies plummeted; Nvidia, which sells the chips that run leading AI models, lost more stock value in a single day(opens a new tab) than any company in history.

The Chinese AI company DeepSeek released a chatbot earlier this year called R1, which drew a huge amount of attention. Most of it focused on the fact(opens a new tab) that a relatively small and unknown company said it had built a chatbot that rivaled the performance of those from the world’s most famous AI companies, but using a fraction of the computer power and cost. As a result, the stocks of many Western tech companies plummeted; Nvidia, which sells the chips that run leading AI models, lost more stock value in a single day(opens a new tab) than any company in history.

Some of that attention involved an element of accusation. Sources alleged(opens a new tab) that DeepSeek had obtained(opens a new tab), without permission, knowledge from OpenAI’s proprietary o1 model by using a technique known as distillation. Much of the news coverage(opens a new tab) framed this possibility as a shock to the AI industry, implying that DeepSeek had discovered a new, more efficient way to build AI.

But distillation, also called knowledge distillation, is a widely used tool in AI, a subject of computer science research going back a decade and a tool that big tech companies use on their own models. “Distillation is one of the most important tools that companies have today to make models more efficient,” said Enric Boix-Adsera(opens a new tab), a researcher who studies distillation at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Will AI outsmart human intelligence? – with ‘Godfather of AI’ Geoffrey Hinton

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

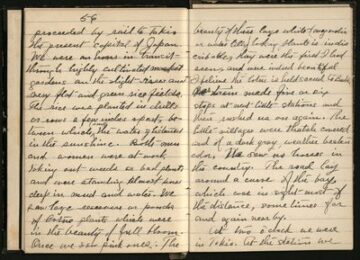

Lonely Diarist of the High Seas

April White at JSTOR Daily:

“The sea is a stranger to me,” Sheldon confessed in the first pages of her journal, yet the thirty-six-year-old had not hesitated a moment when she had been asked, two days earlier, to join the voyage as the stewardess—the only woman on the crew for the sixty-five-day trip to Hong Kong and back, with stops for additional passengers and cargo in Japan and Hawai‘i. For Sheldon, who had been born into a farming family in central Wisconsin before the Civil War, and for other women like her, the position of ship stewardess was a rare and, from the outside, glamorous chance to see the world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In her travels, Sheldon would see things most Americans had encountered only in books or on canvas. “The sunset was beautiful,” she wrote on her first evening aboard the Belgic, “one of those soft pink and yellow tinted skies which we see in pictures and think was created by the artist just to see what he could do. I know now they are real.”

“The sea is a stranger to me,” Sheldon confessed in the first pages of her journal, yet the thirty-six-year-old had not hesitated a moment when she had been asked, two days earlier, to join the voyage as the stewardess—the only woman on the crew for the sixty-five-day trip to Hong Kong and back, with stops for additional passengers and cargo in Japan and Hawai‘i. For Sheldon, who had been born into a farming family in central Wisconsin before the Civil War, and for other women like her, the position of ship stewardess was a rare and, from the outside, glamorous chance to see the world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In her travels, Sheldon would see things most Americans had encountered only in books or on canvas. “The sunset was beautiful,” she wrote on her first evening aboard the Belgic, “one of those soft pink and yellow tinted skies which we see in pictures and think was created by the artist just to see what he could do. I know now they are real.”

For at least eight years, between 1892 and 1900, Sheldon worked shipboard for the Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, traveling from San Francisco to Asia and Central America tending to the every need of the women passengers in the first-class, or “saloon,” cabins and doing the ship’s mending. On at least six of those voyages, she kept a detailed record of her travels. Now, more than 125 years later, the Ella Sheldon Diaries have been shared via JSTOR by the University of the Pacific.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The rise of Nazism brought centuries of animosity between Europe’s Catholics and Protestants to an end. Why?

Udi Greenberg in Aeon:

To grasp just how revolutionary this inter-Christian peace was, it’s worth remembering what came before it. Because the mutual hatred between the confessions shaped not only the early modern era, when gruesome acts of violence like St Bartholomew’s Day (1572) and the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) tore Europe apart. Anti-Catholicism and anti-Protestantism remained powerful forces well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and shaped social and political life. The most extreme case was Germany, where the Protestant majority in 1871 unleashed an aggressive campaign of persecution against the Catholic minority. For seven years, state authorities expelled Catholic orders, took over Catholic educational institutions, and censored Catholic publications.

To grasp just how revolutionary this inter-Christian peace was, it’s worth remembering what came before it. Because the mutual hatred between the confessions shaped not only the early modern era, when gruesome acts of violence like St Bartholomew’s Day (1572) and the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) tore Europe apart. Anti-Catholicism and anti-Protestantism remained powerful forces well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and shaped social and political life. The most extreme case was Germany, where the Protestant majority in 1871 unleashed an aggressive campaign of persecution against the Catholic minority. For seven years, state authorities expelled Catholic orders, took over Catholic educational institutions, and censored Catholic publications.

In the Netherlands, Protestant crowds violently attacked Catholic processions; in Austria, a popular movement called ‘Away from Rome’ began a (failed) campaign in 1897 to eradicate Catholicism through mass conversion. Catholics, for their part, were just as hostile to Protestants. In France, Catholic magazines and sermons blamed Protestants for treason, some even called for stripping them of citizenship. Business associations, labour unions and even marching bands were often divided across confessional lines.

Even on an everyday level, it still was common into the 20th century for neighbourhoods, parties and magazines to be strictly Catholic or Protestant.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

‘28 Years Later’

Michael Wood at the LRB:

The events of Danny Boyle’s new film, 28 Years Later, are not too far away. It’s set in the near future, but the prologue takes us back to 2002, which is when Boyle’s earlier film 28 Days Later was released. (There is also 28 Weeks Later, the 2007 sequel directed by Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, but this seems to borrow a piece of the storyline without becoming part of the sequence.) In the first film a virus strikes Britain, killing millions and turning survivors into zombies, smeared with blood and often naked. The prologue to 28 Years Later shows a group of massive zombies killing a priest, who is mysteriously smiling and passes a young boy a cross to remember him by. The priest is sure that this is the end of the world and is ready to welcome it as such.

The events of Danny Boyle’s new film, 28 Years Later, are not too far away. It’s set in the near future, but the prologue takes us back to 2002, which is when Boyle’s earlier film 28 Days Later was released. (There is also 28 Weeks Later, the 2007 sequel directed by Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, but this seems to borrow a piece of the storyline without becoming part of the sequence.) In the first film a virus strikes Britain, killing millions and turning survivors into zombies, smeared with blood and often naked. The prologue to 28 Years Later shows a group of massive zombies killing a priest, who is mysteriously smiling and passes a young boy a cross to remember him by. The priest is sure that this is the end of the world and is ready to welcome it as such.

It’s not the end of the world, but the world has changed. The virus has spread beyond Britain, and continental European nations have found a way of keeping it at bay. But the British haven’t, and the mainland of England, Scotland and Wales has become a vast space of quarantine. The virus is called Rage, allowing for a crisp double meaning: the virus is rage and rage is a virus. To be alive and infected is to be angry.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Giordano Bruno: Oracle of the Infinite

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong – “Truth and Trust” in Cancer Research & Journalism

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

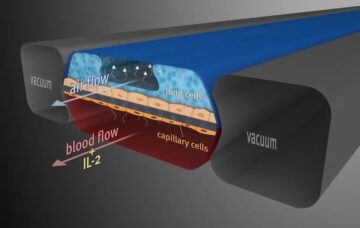

FDA Announces Plan to Phase Out Animal Testing. Will That Work?

Donald Ingber in The Scientist:

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a new roadmap that aims to replace animal testing in the development of new drugs with more human-relevant methods. The goal is to improve drug safety, accelerate the evaluation process, shorten drug development timelines, reduce costs, and spare animal lives. The FDA aims to make animal testing the exception rather than the norm within three to five years. Is this possible?

In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a new roadmap that aims to replace animal testing in the development of new drugs with more human-relevant methods. The goal is to improve drug safety, accelerate the evaluation process, shorten drug development timelines, reduce costs, and spare animal lives. The FDA aims to make animal testing the exception rather than the norm within three to five years. Is this possible?

The FDA has required animal testing of new drugs since the 1930s after more than 125 American adults and children died after ingesting an antibiotic elixir that mistakenly contained the poison found in antifreeze—diethylene glycol—which was then thought to be just a sweetening agent. Animal testing remains the mainstay of drug evaluations by the FDA, and it undoubtedly has helped prevent other potentially dangerous chemicals from reaching patients. However, on the flip side, the results of drug tests in animals fail to predict future responses in humans more than 90 percent of the time.1 It is also likely that many drugs that could have been safe and effective in humans never received approval because they were found to be toxic in early animal studies. Aspirin is a great example; we are all lucky because it was first marketed before 1900.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Tuesday Poem

Bonagameise

I was never sure what it meant,

but it was a loose translation

of my German-American grandmother’s

answer to feeding her family of 11 children.

A soup of green beans and spuds

from her garden, it was flavored by her laughter

and a nearly naked ham bone

rescued from the corner grocer.

The salty stew brewed all day

in a huge pot of water from the pump.

Spiced by her laughter,

it provided a satisfying supper

they ate “in shifts.”

Like a brood of chickens at a trough,

the youngest fed first, sliding

off a bench behind the table

when their bellies were full, making

space for the next in line.

The table wasn’t big enough

to seat them all at once.

by Gail Eisenhart

from Rattle #88, Summer 202

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Monday, July 21, 2025

Sidney Morgenbesser on Naturalism (1966)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

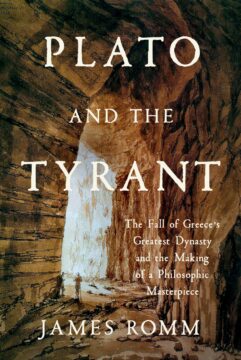

Plato and the Tyrant

Tim Whitmarsh at Literary Review:

James Romm’s Plato and the Tyrant describes the next phase, when the city slid into tyranny under first a father and then his son, both named Dionysius. This is a work of history, but it is as compelling as any novel. Syracuse in the late-classical period found itself locked in a love-hate relationship with Athens. The frenemy cities could not get enough of each other. Plato and the Tyrant reconstructs a crucial chapter in that psychodrama.

Both Dionysius I and II seem to have hosted Plato, the famous Athenian philosopher, in Syracuse. I write ‘seem to’, because the only contemporary ‘evidence’ for Plato’s visit comes in a series of letters attributed to him. Some modern scholars believe these to be forgeries written later in antiquity, designed to give the otherwise shadowy figure of Plato (who barely speaks of himself in his works) a richer, more glamorous biography. Romm is a self-avowed maximalist: he not only accepts as Platonic the parts of the letters relevant to the Syracusan stay but is also open-minded about many of the details archived in the much later biographical accounts of Diodorus Siculus, Plutarch and Diogenes Laertius.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.