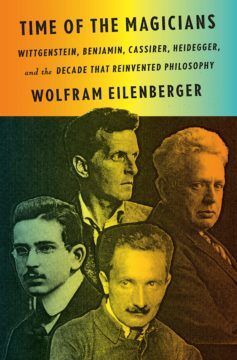

Costica Bradatan in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

“AND WHAT ABOUT unbiased research? What about pure knowledge?” bursts out the more idealistic of the two debaters. Before the other, the more cynical one, even has a chance to answer, the idealist ambushes him with even grander questions: “What about the truth, my dear sir, which is so intimately bound up with freedom, and its martyrs?” We can picture the caustic smile on the cynic’s face. “My good friend,” the cynic answers, “there is no such thing as pure knowledge.” His words come out calmly, fully formed, in sharp contrast to the idealist’s passionate, if sometimes logically disjointed pronouncements. The cynic’s rebuttal is merciless:

“AND WHAT ABOUT unbiased research? What about pure knowledge?” bursts out the more idealistic of the two debaters. Before the other, the more cynical one, even has a chance to answer, the idealist ambushes him with even grander questions: “What about the truth, my dear sir, which is so intimately bound up with freedom, and its martyrs?” We can picture the caustic smile on the cynic’s face. “My good friend,” the cynic answers, “there is no such thing as pure knowledge.” His words come out calmly, fully formed, in sharp contrast to the idealist’s passionate, if sometimes logically disjointed pronouncements. The cynic’s rebuttal is merciless:

Faith is the vehicle of understanding, the intellect is secondary. Your unbiased science is a myth. Faith, a world view, an idea — in short, the will — is always present, and it is then reason’s task to examine and prove it. In the end we always come down to “quod erat demonstrandum.” The very notion of proof contains, psychologically speaking, a strong voluntaristic element.

To the idealist, brought up in the grand tradition of the European Enlightenment, this looks like a mockery of all he stands for. He can’t take the cynic’s reasoning other than as a tasteless joke.

More here.

Our quest centres on this simple question: why do so many languages and cultures identify these North American natives as “the birds from India” (oiseaux d’Inde, or simply dinde in French).

Our quest centres on this simple question: why do so many languages and cultures identify these North American natives as “the birds from India” (oiseaux d’Inde, or simply dinde in French). Truth is, this year has seen plenty of gratitude, instinctively and generously expressed. The people applauding out their windows for emergency responders, the heart signs, the food deliveries to essential workers, the neighborhood trash teams, the looking-in on elders. Online platforms as purpose-built as gratefulness.org and as customarily combative as Twitter have been flooded with counted blessings: for our loved ones, for the Amazon carrier, for our dogs. People gave thanks for simple things, mostly – their families, video chats, the “tall green trees that are older than me,” a hummingbird, the ocean, soup. (“Yep, soup,” says a West Sacramento, California, man.) But many, many other expressions of gratitude took the form of generosity, of trying to give back or pay it forward. The news was filled with stories of people in grocery lines paying for the customer coming next, donations to farmworkers, businesses furnishing free meals to front-line responders.

Truth is, this year has seen plenty of gratitude, instinctively and generously expressed. The people applauding out their windows for emergency responders, the heart signs, the food deliveries to essential workers, the neighborhood trash teams, the looking-in on elders. Online platforms as purpose-built as gratefulness.org and as customarily combative as Twitter have been flooded with counted blessings: for our loved ones, for the Amazon carrier, for our dogs. People gave thanks for simple things, mostly – their families, video chats, the “tall green trees that are older than me,” a hummingbird, the ocean, soup. (“Yep, soup,” says a West Sacramento, California, man.) But many, many other expressions of gratitude took the form of generosity, of trying to give back or pay it forward. The news was filled with stories of people in grocery lines paying for the customer coming next, donations to farmworkers, businesses furnishing free meals to front-line responders. Mark Ellison stood on the raw plywood floor, staring up into the gutted nineteenth-century town house. Above him, joists, beams, and electrical conduits crisscrossed in the half-light like a demented spider’s web. He still wasn’t sure how to build this thing. According to the architect’s plans, this room was to be the master bath—a cocoon of curving plaster shimmering with pinprick lights. But the ceiling made no sense. One half of it was a barrel vault, like the inside of a Roman basilica; the other half was a groin vault, like the nave of a cathedral. On paper, the rounded curves of one vault flowed smoothly into the elliptical curves of the other. But getting them to do so in three dimensions was a nightmare. “I showed the drawings to the bass player in my band,” Ellison said. “He’s a physicist, so I asked him, ‘Could you do the calculus for this?’ He said, ‘No.’ ”

Mark Ellison stood on the raw plywood floor, staring up into the gutted nineteenth-century town house. Above him, joists, beams, and electrical conduits crisscrossed in the half-light like a demented spider’s web. He still wasn’t sure how to build this thing. According to the architect’s plans, this room was to be the master bath—a cocoon of curving plaster shimmering with pinprick lights. But the ceiling made no sense. One half of it was a barrel vault, like the inside of a Roman basilica; the other half was a groin vault, like the nave of a cathedral. On paper, the rounded curves of one vault flowed smoothly into the elliptical curves of the other. But getting them to do so in three dimensions was a nightmare. “I showed the drawings to the bass player in my band,” Ellison said. “He’s a physicist, so I asked him, ‘Could you do the calculus for this?’ He said, ‘No.’ ” He called the next day. We went out for lunch. We went out for dinner. We went out for drinks. We went out for dinner again. We went out for drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and

He called the next day. We went out for lunch. We went out for dinner. We went out for drinks. We went out for dinner again. We went out for drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and IF THE BOOK

IF THE BOOK Joe Biden’s victory instantly obliterated the Democratic Party’s longstanding charge that Russia was hijacking and compromising US elections. The Biden victory, the Democratic Party leaders and their courtiers in the media now insist, is evidence that the democratic process is strong and untainted, that the system works. The elections ratified the will of the people.

Joe Biden’s victory instantly obliterated the Democratic Party’s longstanding charge that Russia was hijacking and compromising US elections. The Biden victory, the Democratic Party leaders and their courtiers in the media now insist, is evidence that the democratic process is strong and untainted, that the system works. The elections ratified the will of the people. When

When  This month has seen a torrent of news about experimental

This month has seen a torrent of news about experimental  Drugs were doubtless important to Benjamin, who had first smoked hashish in Berlin in 1927. They confirmed his approach to reality and revolution, to art and politics—an approach shaped and sharpened by his experience of Ibiza. He stayed on the island two months, returning for another six in the summer of 1933. Wretchedly sad, he buried himself in his remote past, writing of his Berlin childhood. Yet he also wrote in lascivious detail of his surroundings, that other “remote past,” or so it seemed to him, this “outpost of Europe” apparently untouched by modernity. Here, he could face head-on his central idea that modernity atrophied the capacity to experience the world and tell stories. This is why the Ibizan poet Vicente Valero has titled his as-yet-untranslated book on Benjamin in Ibiza Experiencia y probreza (Experience and Poverty), after the title of a little-known essay Benjamin wrote under the spell of the island. In the hallucinatory splendor of Ibiza, with his future cast to the winds, Benjamin formulated what I would count as his major texts—on the storyteller and on the mimetic faculty—as well as inventing new forms for the essay as a crossover genre that linked dreams, ethnography, thought-figures, and storytelling.

Drugs were doubtless important to Benjamin, who had first smoked hashish in Berlin in 1927. They confirmed his approach to reality and revolution, to art and politics—an approach shaped and sharpened by his experience of Ibiza. He stayed on the island two months, returning for another six in the summer of 1933. Wretchedly sad, he buried himself in his remote past, writing of his Berlin childhood. Yet he also wrote in lascivious detail of his surroundings, that other “remote past,” or so it seemed to him, this “outpost of Europe” apparently untouched by modernity. Here, he could face head-on his central idea that modernity atrophied the capacity to experience the world and tell stories. This is why the Ibizan poet Vicente Valero has titled his as-yet-untranslated book on Benjamin in Ibiza Experiencia y probreza (Experience and Poverty), after the title of a little-known essay Benjamin wrote under the spell of the island. In the hallucinatory splendor of Ibiza, with his future cast to the winds, Benjamin formulated what I would count as his major texts—on the storyteller and on the mimetic faculty—as well as inventing new forms for the essay as a crossover genre that linked dreams, ethnography, thought-figures, and storytelling. Though most people associate Nina Simone with the jazz clubs of New York and Paris, she grew up here, in rural Appalachia. Her home is only a few miles from my mother’s house, in an area that is more genteel and diverse than the rest of the region. In western North Carolina, where Nina Simone was raised, and where I still live, we don’t mine coal. We grow apples. While Appalachia technically stretches across

Though most people associate Nina Simone with the jazz clubs of New York and Paris, she grew up here, in rural Appalachia. Her home is only a few miles from my mother’s house, in an area that is more genteel and diverse than the rest of the region. In western North Carolina, where Nina Simone was raised, and where I still live, we don’t mine coal. We grow apples. While Appalachia technically stretches across  SOMETIME AFTER MIDNIGHT ON JUNE 25, 1975,

SOMETIME AFTER MIDNIGHT ON JUNE 25, 1975,  Cosmologists say that they have uncovered hints of an intriguing twisting in the way that ancient light moves across the Universe, which could offer clues about the nature of dark energy — the mysterious force that seems to be pushing the cosmos to expand ever-faster.

Cosmologists say that they have uncovered hints of an intriguing twisting in the way that ancient light moves across the Universe, which could offer clues about the nature of dark energy — the mysterious force that seems to be pushing the cosmos to expand ever-faster.