Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Aristotle conceived of the world in terms of teleological “final causes”; Darwin, or so the story goes, erased purpose and meaning from the world, replacing them with a bloodless scientific algorithm. But should we abandon all talk of meanings and purposes, or instead conceptualize them as emergent rather than fundamental? Philosophers (and former Mindscape guests) Alex Rosenberg and Daniel Dennett recently had an exchange on just this subject, and today we’re going to hear from a working scientist. David Haig is a geneticist and evolutionary biologist who argues that it’s perfectly sensible to perceive meaning as arising through the course of evolution, even if evolution itself is purposeless.

Aristotle conceived of the world in terms of teleological “final causes”; Darwin, or so the story goes, erased purpose and meaning from the world, replacing them with a bloodless scientific algorithm. But should we abandon all talk of meanings and purposes, or instead conceptualize them as emergent rather than fundamental? Philosophers (and former Mindscape guests) Alex Rosenberg and Daniel Dennett recently had an exchange on just this subject, and today we’re going to hear from a working scientist. David Haig is a geneticist and evolutionary biologist who argues that it’s perfectly sensible to perceive meaning as arising through the course of evolution, even if evolution itself is purposeless.

More here.

In the first half of 2020, as the world economy shut down, hundreds of millions of people across the world lost their jobs. Following India’s lockdown on March 24, 10s of millions of displaced migrant workers thronged bus stops waiting for a ride back to their villages. Many gave up and spent weeks on the road walking home. Over 1.5 billion young people were

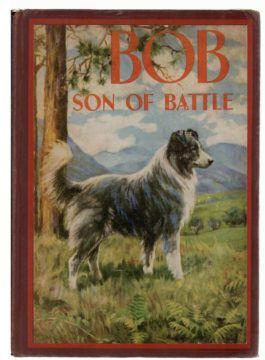

In the first half of 2020, as the world economy shut down, hundreds of millions of people across the world lost their jobs. Following India’s lockdown on March 24, 10s of millions of displaced migrant workers thronged bus stops waiting for a ride back to their villages. Many gave up and spent weeks on the road walking home. Over 1.5 billion young people were  The 1898 children’s classic known in America as Bob, Son of Battle and in England as Owd Bob: The Grey Dog of Kenmuir, by Alfred Ollivant, was long declared—and still is considered, by some—one of the great dog stories of all time, if not the greatest. One reviewer, E.V. Lucas, writing in The Northern Counties Magazine soon after the book was published, felt that this was the first time “full justice” had been done to a dog as a character in fiction. He declared, “Owd Bob is more than a dog story; it is a dog epic.”

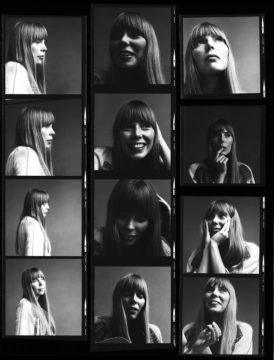

The 1898 children’s classic known in America as Bob, Son of Battle and in England as Owd Bob: The Grey Dog of Kenmuir, by Alfred Ollivant, was long declared—and still is considered, by some—one of the great dog stories of all time, if not the greatest. One reviewer, E.V. Lucas, writing in The Northern Counties Magazine soon after the book was published, felt that this was the first time “full justice” had been done to a dog as a character in fiction. He declared, “Owd Bob is more than a dog story; it is a dog epic.” In 1964, a twenty-year-old Canadian singer named Joan Anderson began composing her own folk songs. They were good folk songs, sturdily constructed and memorable, but the genre corseted her. She would need to roam the mountains and plains of rock and jazz in order to claim her gift. Folk was not enough—but it was what was available to her as a young woman from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the early nineteen-sixties, a woman in possession of an ethereal soprano and a four-string baritone ukulele, the instrument she could afford to buy on her own after her mother nixed a guitar. At nineteen, she left home for art school in Alberta—painting was her first creative outlet—and then began touring, playing in coffeehouses or church basements in Toronto and Calgary and Detroit. For her mother Myrtle’s birthday in 1965, Joan made her a tape with three of the songs she had written, “Urge for Going,” “Born to Take the Highway,” and “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow.” In the folk tradition, they celebrate footloose rambling.

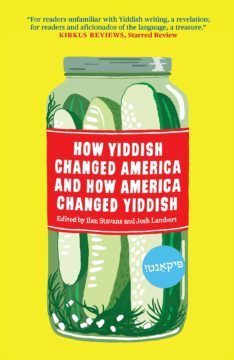

In 1964, a twenty-year-old Canadian singer named Joan Anderson began composing her own folk songs. They were good folk songs, sturdily constructed and memorable, but the genre corseted her. She would need to roam the mountains and plains of rock and jazz in order to claim her gift. Folk was not enough—but it was what was available to her as a young woman from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the early nineteen-sixties, a woman in possession of an ethereal soprano and a four-string baritone ukulele, the instrument she could afford to buy on her own after her mother nixed a guitar. At nineteen, she left home for art school in Alberta—painting was her first creative outlet—and then began touring, playing in coffeehouses or church basements in Toronto and Calgary and Detroit. For her mother Myrtle’s birthday in 1965, Joan made her a tape with three of the songs she had written, “Urge for Going,” “Born to Take the Highway,” and “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow.” In the folk tradition, they celebrate footloose rambling. ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO, when most American Jews were immigrants from Eastern Europe, nearly every Jew in the United States spoke Yiddish, but no one gave it any respect. Today, by contrast, everyone is full of affection for Yiddish, even though almost no one speaks it. Though one hears from every synagogue pulpit and reads in most university Jewish Studies mission statements that Hebrew is the eternal and unifying language of the Jewish experience, Yiddish maintains an emotional claim on the descendants of Eastern European Jews, as well as leaving an indelible imprint on the popular culture created by, for, and among these immigrants and their offspring. Is this valorization of Yiddish commensurate with knowledge and appreciation of — or respect for — the language and the culture it created beyond the lexicon of sentimental melodies, off-color jokes, and redefined adjectives? One could gesture to the 2020 Seth Rogen film An American Pickle without having to answer the question further. Emotional relationships can often lead in nonrational directions, seldom directed by facts.

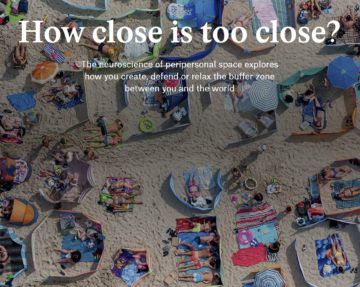

ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO, when most American Jews were immigrants from Eastern Europe, nearly every Jew in the United States spoke Yiddish, but no one gave it any respect. Today, by contrast, everyone is full of affection for Yiddish, even though almost no one speaks it. Though one hears from every synagogue pulpit and reads in most university Jewish Studies mission statements that Hebrew is the eternal and unifying language of the Jewish experience, Yiddish maintains an emotional claim on the descendants of Eastern European Jews, as well as leaving an indelible imprint on the popular culture created by, for, and among these immigrants and their offspring. Is this valorization of Yiddish commensurate with knowledge and appreciation of — or respect for — the language and the culture it created beyond the lexicon of sentimental melodies, off-color jokes, and redefined adjectives? One could gesture to the 2020 Seth Rogen film An American Pickle without having to answer the question further. Emotional relationships can often lead in nonrational directions, seldom directed by facts. Heini Hediger, a noted 20th-century Swiss biologist and zoo director, knew that animals ran away when they felt unsafe. But when he set about designing and building zoos himself, he realised he needed a more precise understanding of how animals behaved when put in proximity to one another. Hediger decided to investigate the flight response systematically, something that no one had done before.

Heini Hediger, a noted 20th-century Swiss biologist and zoo director, knew that animals ran away when they felt unsafe. But when he set about designing and building zoos himself, he realised he needed a more precise understanding of how animals behaved when put in proximity to one another. Hediger decided to investigate the flight response systematically, something that no one had done before. The beating heart of literature is writers’ engagement with sadness and the conflicts of their time. Many of these conflicts are centred on wealth and access to natural resources: land, water, mineral, forest, stone, sand, clean air. Big money, often with the aid of big media, attempts to shape public opinion about who controls the world, who deserves what, how resources ought to be shared. In a similar vein, traditional hegemonies in India – patriarchy and the caste system – try to control the stories we tell about each other.

The beating heart of literature is writers’ engagement with sadness and the conflicts of their time. Many of these conflicts are centred on wealth and access to natural resources: land, water, mineral, forest, stone, sand, clean air. Big money, often with the aid of big media, attempts to shape public opinion about who controls the world, who deserves what, how resources ought to be shared. In a similar vein, traditional hegemonies in India – patriarchy and the caste system – try to control the stories we tell about each other. THERE’S A WEALTH OF

THERE’S A WEALTH OF The Covid-19 pandemic has made the world feel lonelier than ever as people have been shut away in their homes, aching to gather with their loved ones again. This instinct to evade loneliness is deeply engrained in our brains, and a new study published in the journal

The Covid-19 pandemic has made the world feel lonelier than ever as people have been shut away in their homes, aching to gather with their loved ones again. This instinct to evade loneliness is deeply engrained in our brains, and a new study published in the journal

More than 40 years ago, three psychologists published

More than 40 years ago, three psychologists published  Thea Riofrancos in The Baffler:

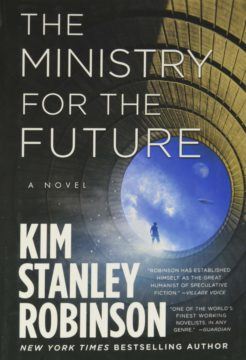

Thea Riofrancos in The Baffler: Gerry Canavan in the LA Review of Books:

Gerry Canavan in the LA Review of Books: