Suzanne Schneider in n+1:

Suzanne Schneider in n+1:

FLOATING SOMEWHERE BETWEEN the optimism that Donald Trump will soon be fired by the American people and the fear that he will eke out a victory, a number of anxious questions circulate: Will he honor the results? Will he try to discredit the election? Will the task of deciding the presidency come down to the courts, for the second time in two decades? What if he refuses to go? Will the military really dispatch him with the swiftness that Joe Biden has promised? What if the transfer of power happens but is anything but peaceful—accompanied by protestors, police, vigilantes, and federal troops facing off on American streets? Pundits stress how unprecedented, and thus dangerous, it is to be even asking such questions; friends share ominous magazine articles about right-wing militias gearing up for civil war. In major cities, corporations are boarding up their storefronts in advance of Election Day.

For many scholars like myself, whose academic work chiefly concerns developments in the Global South, there is a certain familiarity to this disaster-in-the-making. The United States is facing a legitimation crisis of epic proportions, one that will not evaporate should Joe Biden oust Trump from the presidency.

More here.

Nicola Miller in Boston Review:

Nicola Miller in Boston Review: Gray never bought the idea that his book was a handbook for despair. His subject was humility; his target any ideology that believed it possessed anything more than doubtful and piecemeal answers to vast and changing questions. The cat book is written in that spirit. If like me you read with a pencil to hand, you will be underlining constantly with a mix of purring enjoyment and frequent exclamation marks. “Consciousness has been overrated,” Gray will write, coolly. Or “the flaw in rationalism is the belief that human beings can live by applying a theory”. Or “human beings quickly lose their humanity but cats never stop being cats”. He concludes with a 10-point list of how cats might give their anxious, unhappy, self-conscious human companions hints “to live less awkwardly”. These range from “never try to persuade human beings to be reasonable”, to “do not look for meaning in your suffering” to “sleep for the joy of sleeping”.

Gray never bought the idea that his book was a handbook for despair. His subject was humility; his target any ideology that believed it possessed anything more than doubtful and piecemeal answers to vast and changing questions. The cat book is written in that spirit. If like me you read with a pencil to hand, you will be underlining constantly with a mix of purring enjoyment and frequent exclamation marks. “Consciousness has been overrated,” Gray will write, coolly. Or “the flaw in rationalism is the belief that human beings can live by applying a theory”. Or “human beings quickly lose their humanity but cats never stop being cats”. He concludes with a 10-point list of how cats might give their anxious, unhappy, self-conscious human companions hints “to live less awkwardly”. These range from “never try to persuade human beings to be reasonable”, to “do not look for meaning in your suffering” to “sleep for the joy of sleeping”. To write as an ironist, especially today, is to risk that the reader loses patience with hedging, backtracking, spirals of cleverness. But sometimes the layers of the onion ensure the purity of the tears. “That Was Now, This Is Then” is anchored by “Collins Ferry Landing,” an elegy for the poet’s father. Its middle section, in prose, begins by addressing Seshadri’s father in the self-amused voice that is typical for this writer: “I have a friend. (You’ll be glad to know.) She and I work together. (You’ll be glad to know I still have a job.) She’s an ally. She’s sympathetic.” But it turns out that this sympathetic ally has done something terrible. The poet had been speaking about his loss (“I was telling her about you”) and then shied away from it into a galaxy of other subjects (“I was describing cultures of shame evolving across millennia; economies of scarcity versus economies of surplus. … Deep India, strewn with elephants and cobras”). And then the woman does this: “She put her right hand on my left arm and said, ‘He’ll always be with you. In your heart.’”

To write as an ironist, especially today, is to risk that the reader loses patience with hedging, backtracking, spirals of cleverness. But sometimes the layers of the onion ensure the purity of the tears. “That Was Now, This Is Then” is anchored by “Collins Ferry Landing,” an elegy for the poet’s father. Its middle section, in prose, begins by addressing Seshadri’s father in the self-amused voice that is typical for this writer: “I have a friend. (You’ll be glad to know.) She and I work together. (You’ll be glad to know I still have a job.) She’s an ally. She’s sympathetic.” But it turns out that this sympathetic ally has done something terrible. The poet had been speaking about his loss (“I was telling her about you”) and then shied away from it into a galaxy of other subjects (“I was describing cultures of shame evolving across millennia; economies of scarcity versus economies of surplus. … Deep India, strewn with elephants and cobras”). And then the woman does this: “She put her right hand on my left arm and said, ‘He’ll always be with you. In your heart.’” Susan Simien was born and raised in San Francisco, but he had begun to feel like a stranger in his hometown. In the Nineties, when Simien was growing up, the Ingleside neighborhood where he lived was diverse—nearly half of its households were, like Simien’s, middle-class and African-American. But in recent years, friends and neighbors had left for more affordable towns and suburbs—so many that Simien had lost track. Over the course of his lifetime, the African-American population in San Francisco had been cut in half. “You can’t throw a rock and hit someone who actually grew up around here,” Simien liked to say.

Susan Simien was born and raised in San Francisco, but he had begun to feel like a stranger in his hometown. In the Nineties, when Simien was growing up, the Ingleside neighborhood where he lived was diverse—nearly half of its households were, like Simien’s, middle-class and African-American. But in recent years, friends and neighbors had left for more affordable towns and suburbs—so many that Simien had lost track. Over the course of his lifetime, the African-American population in San Francisco had been cut in half. “You can’t throw a rock and hit someone who actually grew up around here,” Simien liked to say. What if the North had won the Civil War? That technically factual counterfactual animated almost all of William Faulkner’s writing. The Mississippi novelist was born thirty-two years after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, but he came of age believing in the superiority of the Confederacy: the South might have lost, but the North did not deserve to win. This Lost Cause revisionism appeared everywhere, from the textbooks that Faulkner was assigned growing up to editorials in local newspapers, praising the paternalism and the prosperity of the slavery economy, jury-rigging an alternative justification for secession, canonizing as saints and martyrs those who fought for the C.S.A., and proclaiming the virtues of antebellum society. In contrast with those delusions, Faulkner’s fiction revealed the truth: the Confederacy was both a military and a moral failure.

What if the North had won the Civil War? That technically factual counterfactual animated almost all of William Faulkner’s writing. The Mississippi novelist was born thirty-two years after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, but he came of age believing in the superiority of the Confederacy: the South might have lost, but the North did not deserve to win. This Lost Cause revisionism appeared everywhere, from the textbooks that Faulkner was assigned growing up to editorials in local newspapers, praising the paternalism and the prosperity of the slavery economy, jury-rigging an alternative justification for secession, canonizing as saints and martyrs those who fought for the C.S.A., and proclaiming the virtues of antebellum society. In contrast with those delusions, Faulkner’s fiction revealed the truth: the Confederacy was both a military and a moral failure. I asked Iva and James to tell me everything they knew. They looked uncomfortable, whispering despite the fact that there wasn’t really anyone there but the barista.

I asked Iva and James to tell me everything they knew. They looked uncomfortable, whispering despite the fact that there wasn’t really anyone there but the barista. It seems an innocent enough question: why are males more frequently left-handed than females? But the answer is far from simple, and it reveals fundamental principles of how our psychological and behavioural traits are encoded in our genomes, how variability in those traits arise, and how development is channelled towards specific outcomes. It turns out that the explanation rests on an underlying difference between males and females that has far-reaching consequences for all kinds of traits, including neurodevelopmental disorders.

It seems an innocent enough question: why are males more frequently left-handed than females? But the answer is far from simple, and it reveals fundamental principles of how our psychological and behavioural traits are encoded in our genomes, how variability in those traits arise, and how development is channelled towards specific outcomes. It turns out that the explanation rests on an underlying difference between males and females that has far-reaching consequences for all kinds of traits, including neurodevelopmental disorders. For those awash in anxiety and alienation, who feel that everything is spinning out of control, conspiracy theories are extremely effective emotional tools. For those in low status groups, they provide a sense of superiority: I possess important information most people do not have. For those who feel powerless, they provide agency: I have the power to reject “experts” and expose hidden cabals. As Cass Sunstein of Harvard Law School points out, they provide liberation: If I imagine my foes are completely malevolent, then I can use any tactic I want.

For those awash in anxiety and alienation, who feel that everything is spinning out of control, conspiracy theories are extremely effective emotional tools. For those in low status groups, they provide a sense of superiority: I possess important information most people do not have. For those who feel powerless, they provide agency: I have the power to reject “experts” and expose hidden cabals. As Cass Sunstein of Harvard Law School points out, they provide liberation: If I imagine my foes are completely malevolent, then I can use any tactic I want. “God,” a friend of mine recently confided to me, “needs to make a comeback.”

“God,” a friend of mine recently confided to me, “needs to make a comeback.” Wales mattered to Jan. In midlife, and at more or less the same time as her gender reassignment, she embraced what she called Welsh Republicanism. Her home, Trefan Morys, is in a remote area near the town of Criccieth. You leave the main road, take a long, rutted drive, negotiate the narrow entrance in a high stone wall, and you are suddenly in an enchanted space. Elizabeth was the architect of the garden and Jan the interior designer. You enter the house through a two-part stable door (Jan always greeting you with the words, “Not today, thank you”), into a cozy kitchen, and then the main downstairs room. The walls are lined with eight thousand books, including specially leather-bound editions of Jan’s own. Up the stairs there is another long room, with an old-fashioned stove in the middle. Here are more books, but this space is given over mainly to memorabilia and paintings. Pride of place is given to a six-foot-long painting of Venice, done by Jan, in which every detail of the miraculous city is rendered (including tiny portraits of the two eldest sons, who were very young at the time Jan painted it). Model ships hang from the ceiling, and paintings of ships adorn the walls. Jan loved ships from the time she spied them, as a child, through a telescope as they passed through the Bristol Channel near her family’s home.

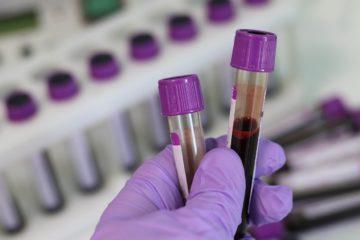

Wales mattered to Jan. In midlife, and at more or less the same time as her gender reassignment, she embraced what she called Welsh Republicanism. Her home, Trefan Morys, is in a remote area near the town of Criccieth. You leave the main road, take a long, rutted drive, negotiate the narrow entrance in a high stone wall, and you are suddenly in an enchanted space. Elizabeth was the architect of the garden and Jan the interior designer. You enter the house through a two-part stable door (Jan always greeting you with the words, “Not today, thank you”), into a cozy kitchen, and then the main downstairs room. The walls are lined with eight thousand books, including specially leather-bound editions of Jan’s own. Up the stairs there is another long room, with an old-fashioned stove in the middle. Here are more books, but this space is given over mainly to memorabilia and paintings. Pride of place is given to a six-foot-long painting of Venice, done by Jan, in which every detail of the miraculous city is rendered (including tiny portraits of the two eldest sons, who were very young at the time Jan painted it). Model ships hang from the ceiling, and paintings of ships adorn the walls. Jan loved ships from the time she spied them, as a child, through a telescope as they passed through the Bristol Channel near her family’s home. The UK National Health Service (NHS) is set to initiate the trial of Galleri blood test that can potentially detect over 50 types of cancers. Developed by GRAIL, the test is capable of detecting early-stage cancers through a simple blood test. In research on patients with cancer signs, the test identified many types like head and neck, ovarian, pancreatic, oesophageal and some blood cancers, which are difficult to diagnose early. The blood test checks for molecular changes. NHS Chief Executive Simon Stevens said: “Early detection – particularly for hard-to-treat conditions like ovarian and pancreatic cancer – has the potential to save many lives. “This promising blood test could therefore be a game-changer in cancer care, helping thousands of more people to get successful treatment.” Anticipated to start in the middle of next year, the GRAIL pilot will involve 165,000 people. This participant population will include 140,000 people aged 50 to 79 years who have no symptoms but will have annual blood tests for three years.

The UK National Health Service (NHS) is set to initiate the trial of Galleri blood test that can potentially detect over 50 types of cancers. Developed by GRAIL, the test is capable of detecting early-stage cancers through a simple blood test. In research on patients with cancer signs, the test identified many types like head and neck, ovarian, pancreatic, oesophageal and some blood cancers, which are difficult to diagnose early. The blood test checks for molecular changes. NHS Chief Executive Simon Stevens said: “Early detection – particularly for hard-to-treat conditions like ovarian and pancreatic cancer – has the potential to save many lives. “This promising blood test could therefore be a game-changer in cancer care, helping thousands of more people to get successful treatment.” Anticipated to start in the middle of next year, the GRAIL pilot will involve 165,000 people. This participant population will include 140,000 people aged 50 to 79 years who have no symptoms but will have annual blood tests for three years. For centuries people have pondered the

For centuries people have pondered the  You might recall the strange case of Matthew J. Mayhew, professor of educational administration at The Ohio State University. In late September he published

You might recall the strange case of Matthew J. Mayhew, professor of educational administration at The Ohio State University. In late September he published  At the heart of Oxford’s effort to produce a Covid vaccine are half a dozen scientists who between them brought decades of experience to the challenge of designing, developing, manufacturing and trialling a

At the heart of Oxford’s effort to produce a Covid vaccine are half a dozen scientists who between them brought decades of experience to the challenge of designing, developing, manufacturing and trialling a