Catherine Nixey in MIL:

I’d been looking forward to the meal for weeks. I already knew what I was going to eat: the rosemary crostini starter, then the lamb with courgette fries. Or maybe the cod. I planned to arrive early and sit in the window at the cool marble counter and watch London go by. In the warm bustle of the restaurant, the condensation would mist the pane. As a treat, I would order myself a glass of white wine while I waited for my friend. It won’t surprise you to hear that the meal never happened. Coronavirus cases started rising exponentially and eating out felt less like indulgence and more like lunacy. Then it became illegal to eat together at all. Soon it became illegal even to eat at a restaurant by yourself. Then everything shut.

I’d been looking forward to the meal for weeks. I already knew what I was going to eat: the rosemary crostini starter, then the lamb with courgette fries. Or maybe the cod. I planned to arrive early and sit in the window at the cool marble counter and watch London go by. In the warm bustle of the restaurant, the condensation would mist the pane. As a treat, I would order myself a glass of white wine while I waited for my friend. It won’t surprise you to hear that the meal never happened. Coronavirus cases started rising exponentially and eating out felt less like indulgence and more like lunacy. Then it became illegal to eat together at all. Soon it became illegal even to eat at a restaurant by yourself. Then everything shut.

The cost of these lost lunches has been totted up many times: the trains not taken, the taxis not flagged down, the desserts not eaten, the waiters not tipped. Then there is the emotional toll, too. Spirits are flagging, the lonely are getting lonelier, the world is wilting. Covid has already disrupted so much of how we live. It has altered something else, as well – time itself. Not so long ago, we had merely months and years. Things happened in November or in December, last year or this. Some events are so big that they divide the world into before and after, into the present and an increasingly alien past. Wars do this, and the pandemic has, too. Coronavirus has cut a trench through time.

The very recent past is suddenly another country. Now, amateur archaeologists of our own existence, we sort through our possessions and stumble on small relics from “then”, that strange place we used to live: a bus pass, a lipstick, a smart watch, a pair of shoes with the heels worn down, work clothes that, after just six months in stretchy active-wear, feel as stiff and preposterous as whalebone.

More here.

On May 19, Ashwin Sah posted the best result ever on one of the most important questions in combinatorics. It was a moment that might have called for a celebratory drink, only Sah wasn’t old enough to order one.

On May 19, Ashwin Sah posted the best result ever on one of the most important questions in combinatorics. It was a moment that might have called for a celebratory drink, only Sah wasn’t old enough to order one.

In 1893 financial panic triggered a four-year depression in the United States, then the most severe in the nation’s history. Bank runs, shuttered factories, and plummeting wheat prices put millions out of work. In Chicago alone, as many as 180,000 workers were jobless by the end of the year.

In 1893 financial panic triggered a four-year depression in the United States, then the most severe in the nation’s history. Bank runs, shuttered factories, and plummeting wheat prices put millions out of work. In Chicago alone, as many as 180,000 workers were jobless by the end of the year. Seamus Perry and Mark Ford discuss the life and work of Louis MacNeice, the Irish poet of psychic divisions and authoritative fretfulness.

Seamus Perry and Mark Ford discuss the life and work of Louis MacNeice, the Irish poet of psychic divisions and authoritative fretfulness. A certain scene between Marguerite Duras and Susan Sontag, told to me by someone who was friends with both and seated between them while Susan was visiting Paris, goes like this: Duras had just made a new film, and, in keeping with her character, she spoke at Susan in a monologic séance, going on and on about herself, her new film, and critical reactions to her new film. After speaking for most of the occasion they were together, Duras suddenly quieted and seemed to notice Sontag qua Sontag, and not just any old audience to her tirade. “Susan! My goodness. I have only talked and talked, and I haven’t let you speak a word! Please, tell me everything.” At this, Susan—or can we even say “poor Susan”—beamed like a child who was finally getting the attention she’d sought. Duras continued, “I want every detail! What did you think of my new film?”

A certain scene between Marguerite Duras and Susan Sontag, told to me by someone who was friends with both and seated between them while Susan was visiting Paris, goes like this: Duras had just made a new film, and, in keeping with her character, she spoke at Susan in a monologic séance, going on and on about herself, her new film, and critical reactions to her new film. After speaking for most of the occasion they were together, Duras suddenly quieted and seemed to notice Sontag qua Sontag, and not just any old audience to her tirade. “Susan! My goodness. I have only talked and talked, and I haven’t let you speak a word! Please, tell me everything.” At this, Susan—or can we even say “poor Susan”—beamed like a child who was finally getting the attention she’d sought. Duras continued, “I want every detail! What did you think of my new film?” Just before Thanksgiving in November 2005, paediatrician Ruchi Gupta gathered some parents of children with food allergies in an office building. She aimed to collect data on their knowledge and beliefs about allergies, but the conversation quickly turned emotional. One parent described how her family wouldn’t be joining the big Thanksgiving gathering because of her son’s allergy. “She started crying and she was very emotional about it, and said they were just going to do Thanksgiving on their own,” recalls Gupta, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern and Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. “The whole focus group became pretty intense and tissue boxes came out.” The meeting was planned to last an hour, but people stayed well into a third. Other parents opened up about their distress. “They started talking about their experiences in every realm of life: people who didn’t believe them, even in their own families. A lot of times the grandparents would say, ‘Oh, you’re just over-protective. We didn’t have this in my day’.”

Just before Thanksgiving in November 2005, paediatrician Ruchi Gupta gathered some parents of children with food allergies in an office building. She aimed to collect data on their knowledge and beliefs about allergies, but the conversation quickly turned emotional. One parent described how her family wouldn’t be joining the big Thanksgiving gathering because of her son’s allergy. “She started crying and she was very emotional about it, and said they were just going to do Thanksgiving on their own,” recalls Gupta, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern and Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. “The whole focus group became pretty intense and tissue boxes came out.” The meeting was planned to last an hour, but people stayed well into a third. Other parents opened up about their distress. “They started talking about their experiences in every realm of life: people who didn’t believe them, even in their own families. A lot of times the grandparents would say, ‘Oh, you’re just over-protective. We didn’t have this in my day’.” On a scale of 0 to 10, I’d say my happiness ranks at about a 6. I’d guess my wife’s is at least a 9. I try not to envy her natural Spanish

On a scale of 0 to 10, I’d say my happiness ranks at about a 6. I’d guess my wife’s is at least a 9. I try not to envy her natural Spanish  Tennyson’s poem ‘Mariana’ has gone everywhere in the world since 1830. A professional scholar in Uruguay, Papua New Guinea or New Haven, Connecticut, reading the lines ‘Weeded and worn the ancient thatch/Upon the lonely moated grange’ might want to ask a few questions. Do English houses ever have moats? (Yes — Ightham Mote and Madresfield Court are famous examples.) Can we find houses with a humble thatch and also a moat? (A harder question – Tennyson’s poem set a vogue in landscape design as well as poetry.) Or, taking a different tack, where does the use of the word ‘moat’ as a verb come from? (Easy — ‘moated grange’ is from the poem’s subject, Measure for Measure.) What sort of word was it by 1830? (Harder — it comes up in translations with a taste for the archaic, and technical descriptions of architecture. Is it picturesque in a way that Shakespeare’s use isn’t?) These are interesting questions that might lead to some kind of enlightenment.

Tennyson’s poem ‘Mariana’ has gone everywhere in the world since 1830. A professional scholar in Uruguay, Papua New Guinea or New Haven, Connecticut, reading the lines ‘Weeded and worn the ancient thatch/Upon the lonely moated grange’ might want to ask a few questions. Do English houses ever have moats? (Yes — Ightham Mote and Madresfield Court are famous examples.) Can we find houses with a humble thatch and also a moat? (A harder question – Tennyson’s poem set a vogue in landscape design as well as poetry.) Or, taking a different tack, where does the use of the word ‘moat’ as a verb come from? (Easy — ‘moated grange’ is from the poem’s subject, Measure for Measure.) What sort of word was it by 1830? (Harder — it comes up in translations with a taste for the archaic, and technical descriptions of architecture. Is it picturesque in a way that Shakespeare’s use isn’t?) These are interesting questions that might lead to some kind of enlightenment. Cultured meat, produced in bioreactors without the slaughter of an animal, has been approved for sale by a regulatory authority for the first time. The development has been hailed as a landmark moment across the meat industry.

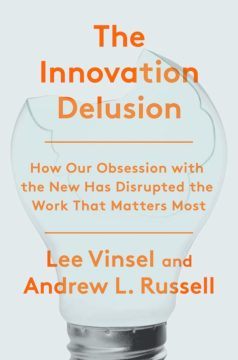

Cultured meat, produced in bioreactors without the slaughter of an animal, has been approved for sale by a regulatory authority for the first time. The development has been hailed as a landmark moment across the meat industry. I should hate The Innovation Delusion. I’ve made a career as a futurist in Silicon Valley, helping big companies think about the business implications and commercial opportunities of emerging technologies. My father-in-law spent his career in the computer industry, my wife helps run her school’s “maker lab,” and my son graduated from

I should hate The Innovation Delusion. I’ve made a career as a futurist in Silicon Valley, helping big companies think about the business implications and commercial opportunities of emerging technologies. My father-in-law spent his career in the computer industry, my wife helps run her school’s “maker lab,” and my son graduated from  Since 2016, liberals have adopted a strategy of delegitimisation, condemning Mr Trump, and his supporters, for degrading political life. A grass-roots campaign of Democrats, Independents and Never-Trump conservatives, which describes itself as the “Resistance”, has also protested Mr Trump at every turn: over his treatment of women, the separation of immigrant families and his hostility towards Black Lives Matter.

Since 2016, liberals have adopted a strategy of delegitimisation, condemning Mr Trump, and his supporters, for degrading political life. A grass-roots campaign of Democrats, Independents and Never-Trump conservatives, which describes itself as the “Resistance”, has also protested Mr Trump at every turn: over his treatment of women, the separation of immigrant families and his hostility towards Black Lives Matter. I’

I’ The old net delusion was naïve but internally consistent. The new net delusion is fragmented and self-contradictory. It vacillates between radical pessimism about the effects of digital platforms and boosterism when new online happenings seem to revive the old cyber-utopian dreams.

The old net delusion was naïve but internally consistent. The new net delusion is fragmented and self-contradictory. It vacillates between radical pessimism about the effects of digital platforms and boosterism when new online happenings seem to revive the old cyber-utopian dreams. ‘Oh – Vivienne! Was there ever such a torture since life began!’ a dazed Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary in 1930 after a typically miserable visit from T S Eliot and his wife. Vivien had been paranoid and cryptic, rambling about hornets under her bed as Tom tried to cover up with ‘longwinded and facetious’ stories, as she wrote to Vanessa Bell. What agony ‘to bear her on ones shoulders,’ Woolf marvelled, ‘biting, wriggling, raving, scratching, unwholesome, powdered … This bag of ferrets is what Tom wears round his neck.’ To offset this grotesque picture, Ann Pasternak Slater provides a kinder but equally revealing image of the Eliots’ early married life together, supplied by their friend Brigit Patmore. While they were all in the chemist’s one day, Vivien, a keen dancer, decided to demonstrate a ballet move, holding onto the counter with one hand, rising on her toes and putting out her other hand, ‘which Tom took in his right hand, watching Vivien’s feet with ardent interest whilst he supported her with real tenderness … Most husbands would have said, “Not here, for Heaven’s sake!”’ It’s a brilliant snapshot of their marital pas de deux, Viv letting it all hang out, Tom enabling.

‘Oh – Vivienne! Was there ever such a torture since life began!’ a dazed Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary in 1930 after a typically miserable visit from T S Eliot and his wife. Vivien had been paranoid and cryptic, rambling about hornets under her bed as Tom tried to cover up with ‘longwinded and facetious’ stories, as she wrote to Vanessa Bell. What agony ‘to bear her on ones shoulders,’ Woolf marvelled, ‘biting, wriggling, raving, scratching, unwholesome, powdered … This bag of ferrets is what Tom wears round his neck.’ To offset this grotesque picture, Ann Pasternak Slater provides a kinder but equally revealing image of the Eliots’ early married life together, supplied by their friend Brigit Patmore. While they were all in the chemist’s one day, Vivien, a keen dancer, decided to demonstrate a ballet move, holding onto the counter with one hand, rising on her toes and putting out her other hand, ‘which Tom took in his right hand, watching Vivien’s feet with ardent interest whilst he supported her with real tenderness … Most husbands would have said, “Not here, for Heaven’s sake!”’ It’s a brilliant snapshot of their marital pas de deux, Viv letting it all hang out, Tom enabling. IT IS CUSTOMARY TO START an essay about Kafka by emphasizing how impossible it is to write about Kafka, then apologizing for making a doomed attempt. This gimmick has a distinguished lineage. “How, after all, does one dare, how can one presume?” Cynthia Ozick asks in the New Republic before she presumes for several ravishing pages. In the Paris Review, Joshua Cohen insists that “being asked to write about Kafka is like being asked to describe the Great Wall of China by someone who’s standing just next to it. The only honest thing to do is point.” But far from pointing, he gestures for thousands of words.

IT IS CUSTOMARY TO START an essay about Kafka by emphasizing how impossible it is to write about Kafka, then apologizing for making a doomed attempt. This gimmick has a distinguished lineage. “How, after all, does one dare, how can one presume?” Cynthia Ozick asks in the New Republic before she presumes for several ravishing pages. In the Paris Review, Joshua Cohen insists that “being asked to write about Kafka is like being asked to describe the Great Wall of China by someone who’s standing just next to it. The only honest thing to do is point.” But far from pointing, he gestures for thousands of words.