Category: Recommended Reading

Stanford team creates cellular atlas of the human lung

Bob Yirka in Phys.Org:

A team of researchers from multiple departments at Stanford University has created a cellular atlas of the human lung that highlights the dozens of cell types that comprise parts of the lungs. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the researchers describe their work (mostly involving single-cell RNA sequencing) and some of the things they learned about the lungs during their effort. To create the atlas, the researchers collected tissue samples from bronchiole, bronchi and alveolar regions of the lungs, along with associated blood samples. Each of the samples was broken down into its cellular components, which were then sorted by type: immune, epithelial, endothelia or stomal. The researchers generated transcriptomes for approximately 75,000 cells. Using markers, the team then clustered the cells to reveal 58 distinct cell populations. In so doing, they were able to generate expression profiles for 91 percent of lung types—and also found 14 lung cell types not previously known to science. They also found approximately 200 markers that could be used to identify the unknown types they found.

A team of researchers from multiple departments at Stanford University has created a cellular atlas of the human lung that highlights the dozens of cell types that comprise parts of the lungs. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the researchers describe their work (mostly involving single-cell RNA sequencing) and some of the things they learned about the lungs during their effort. To create the atlas, the researchers collected tissue samples from bronchiole, bronchi and alveolar regions of the lungs, along with associated blood samples. Each of the samples was broken down into its cellular components, which were then sorted by type: immune, epithelial, endothelia or stomal. The researchers generated transcriptomes for approximately 75,000 cells. Using markers, the team then clustered the cells to reveal 58 distinct cell populations. In so doing, they were able to generate expression profiles for 91 percent of lung types—and also found 14 lung cell types not previously known to science. They also found approximately 200 markers that could be used to identify the unknown types they found.

The team found they were able to use the resulting atlas to trace hormone targets in the lungs. In so doing, they found that some hormone receptors were expressed widely across different parts of the lungs, while others were not. And as part of this secondary effort, the researchers also identified areas where 233 genes are expressed that could be used by scientists working on understanding and curing a wide variety of lung diseases.

More here.

Will Trump Burn the Evidence?

Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act.

Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act.

Trump cannot abide documentation for fear of disclosure, and cannot abide disclosure for fear of disparagement. For decades, in private life, he required people who worked with him, and with the Trump Organization, to sign nondisclosure agreements, pledging never to say a bad word about him, his family, or his businesses. He also extracted nondisclosure agreements from women with whom he had or is alleged to have had sex, including both of his ex-wives. In 2015 and 2016, he required these contracts from people involved in his campaign, including a distributor of his “Make America Great Again” hats. (Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign required N.D.A.s from some employees, too. In 2020, Joe Biden called on Michael Bloomberg to release his former employees from such agreements.) In 2017, Trump, unable to distinguish between private life and public service, carried his practice of requiring nondisclosure agreements into the Presidency, demanding that senior White House staff sign N.D.A.s. According to the Washington Post, at least one of them, in draft form, included this language: “I understand that the United States Government or, upon completion of the term(s) of Mr. Donald J. Trump, an authorized representative of Mr. Trump, may seek any remedy available to enforce this Agreement including, but not limited to, application for a court order prohibiting disclosure of information in breach of this Agreement.” Aides warned him that, for White House employees, such agreements are likely not legally enforceable. The White House counsel, Don McGahn, refused to distribute them; eventually, he relented, and the chief of staff, Reince Priebus, pressured employees to sign them.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Things I Didn’t Know I Loved

it’s 1962 March 28th

I’m sitting by the window on the Prague-Berlin train

night is falling

I never knew I liked

night descending like a tired bird on a smoky wet plain

I don’t like

comparing nightfall to a tired bird

I didn’t know I loved the earth

can someone who hasn’t worked the earth love it

I’ve never worked the earth

it must be my only Platonic love

and here I’ve loved rivers all this time

whether motionless like this they curl skirting the hills

European hills crowned with chateaus

or whether stretched out flat as far as the eye can see

I know you can’t wash in the same river even once

I know the river will bring new lights you’ll never see

I know we live slightly longer than a horse but not nearly as long as a crow

I know this has troubled people before

and will trouble those after me

I know all this has been said a thousand times before

and will be said after me

I didn’t know I loved the sky

cloudy or clear

the blue vault Andrei studied on his back at Borodino

in prison I translated both volumes of War and Peace into Turkish

I hear voices

not from the blue vault but from the yard

the guards are beating someone again

I didn’t know I loved trees

bare beeches near Moscow in Peredelkino

they come upon me in winter noble and modest

beeches are Russian the way poplars are Turkish

“the poplars of Izmir

losing their leaves. . .

they call me The Knife. . .

lover like a young tree. . .

I blow stately mansions sky-high”

in the Ilgaz woods in 1920 I tied an embroidered linen handkerchief

to a pine bough for luck

John Waters and Lynn Tillman in Conversation

Lovers in the Hands of a Patient God

S. G. Belknap at The Point:

James never stopped short in an exploration or an argument—and for him that meant never stopping short of the biggest question: the religious one. His thinking of the late 1890s kept pushing in this direction, culminating in the Gifford Lectures delivered in Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, the lectures known to posterity as The Varieties of Religious Experience. James felt that the question of this world and the other world was somehow decisive for all of us, whichever way we answered it. And that included a whole lot of answers for someone like William James—attender of séances, consulter of mediums and all-around junkie for experience. In “The Will to Believe,” James is mostly interested in leveling the playing field vis-à-vis his skeptical colleagues. When it comes down to it, he wonders, why can’t we just go ahead and will the belief in God? The stern-minded skeptic is happy to object: we have no evidence for it. James replies: we have no evidence against it. The skeptic concedes, and objects again: well, then, I’ll wait until we have decisive evidence one way or the other. William James: to spend a life in indecision is no different from choosing against it; for example, if you have no decisive evidence that a potential career is best for you, you can’t just delay your decision until you die. The skeptic: but religion is not like that. William James: why not?

James never stopped short in an exploration or an argument—and for him that meant never stopping short of the biggest question: the religious one. His thinking of the late 1890s kept pushing in this direction, culminating in the Gifford Lectures delivered in Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, the lectures known to posterity as The Varieties of Religious Experience. James felt that the question of this world and the other world was somehow decisive for all of us, whichever way we answered it. And that included a whole lot of answers for someone like William James—attender of séances, consulter of mediums and all-around junkie for experience. In “The Will to Believe,” James is mostly interested in leveling the playing field vis-à-vis his skeptical colleagues. When it comes down to it, he wonders, why can’t we just go ahead and will the belief in God? The stern-minded skeptic is happy to object: we have no evidence for it. James replies: we have no evidence against it. The skeptic concedes, and objects again: well, then, I’ll wait until we have decisive evidence one way or the other. William James: to spend a life in indecision is no different from choosing against it; for example, if you have no decisive evidence that a potential career is best for you, you can’t just delay your decision until you die. The skeptic: but religion is not like that. William James: why not?

more here.

Harold Bloom Finally Betrays How Little He Really Understood Literature

Philip Hensher at The Spectator:

No one is going to base a claim for Bloom’s merits on this final book. But it does indicate, with painful acuity, that the critic may have had little understanding of how literature is made — which is not out of ideas, as Mallarmé patiently explained to Cézanne. It doesn’t achieve its effects by saying ‘this is funny’ or ‘this is so moving’. It relishes its own voice — and to dwell on what it has stolen from others misses its ambition.

No one is going to base a claim for Bloom’s merits on this final book. But it does indicate, with painful acuity, that the critic may have had little understanding of how literature is made — which is not out of ideas, as Mallarmé patiently explained to Cézanne. It doesn’t achieve its effects by saying ‘this is funny’ or ‘this is so moving’. It relishes its own voice — and to dwell on what it has stolen from others misses its ambition.

Bloom spent his life talking about literature to a captive audience, and at the end it looks to me as if he missed the point, saying with grandiose but comic insufficiency of evidence that Yeats’s ‘Under Ben Bulben’ is ‘of a badness not to be believed’. Well, that was Yeats’s last word, and this is Harold Bloom’s. I wonder — as Ronald Firbank used to say when he heard something unusually absurd.

more here.

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

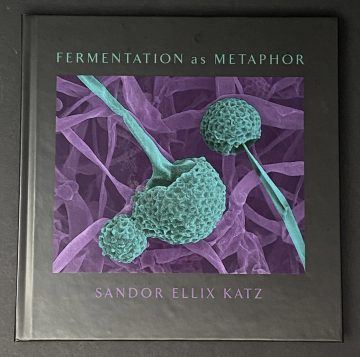

Fermentation as Metaphor: An Interview with Sandor Katz

From Emergence Magazine:

Emergence Magazine: You describe yourself as a fermentation revivalist so I wonder if we could start by having you share a bit about what that means to you.

Sandor Katz: Well, sure. The reason I started calling myself a fermentation revivalist is from my sense of how common fermentation has been in the not too distant past and it’s so integral to all of our food traditions. Whatever part of the world our ancestors came from, fermentation is an essential part of how people make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them, but in the last several generations and at different paces in different parts of the world, people have become increasingly distanced from the production of food and all of the processes that we use to transform the raw products of agriculture into all of the foods that people eat and drink. And it so happens that the same time period where these processes became more mysterious and distanced to people is also the time when the war on bacteria developed. People developed this fear, projected all of their fear of bacteria onto these ancient and important transformative fermentation processes. So when I call myself a fermentation revivalist, it’s about demystifying the process of fermentation, getting people comfortable with it, and encouraging people to familiarize themselves with processes that are extremely important but have become mysterious for people.

Sandor Katz: Well, sure. The reason I started calling myself a fermentation revivalist is from my sense of how common fermentation has been in the not too distant past and it’s so integral to all of our food traditions. Whatever part of the world our ancestors came from, fermentation is an essential part of how people make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them, but in the last several generations and at different paces in different parts of the world, people have become increasingly distanced from the production of food and all of the processes that we use to transform the raw products of agriculture into all of the foods that people eat and drink. And it so happens that the same time period where these processes became more mysterious and distanced to people is also the time when the war on bacteria developed. People developed this fear, projected all of their fear of bacteria onto these ancient and important transformative fermentation processes. So when I call myself a fermentation revivalist, it’s about demystifying the process of fermentation, getting people comfortable with it, and encouraging people to familiarize themselves with processes that are extremely important but have become mysterious for people.

More here.

The biological research putting purpose back into life

Philip Ball in Aeon:

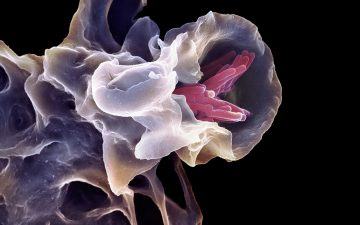

Animal immune systems depend on white blood cells called macrophages that devour and engulf invaders. The cells pursue with determination and gusto: under a microscope you can watch a blob-like macrophage chase a bacterium across the slide, switching course this way and that as its prey tries to escape through an obstacle course of red blood cells, before it finally catches the rogue microbe and gobbles it up.

Animal immune systems depend on white blood cells called macrophages that devour and engulf invaders. The cells pursue with determination and gusto: under a microscope you can watch a blob-like macrophage chase a bacterium across the slide, switching course this way and that as its prey tries to escape through an obstacle course of red blood cells, before it finally catches the rogue microbe and gobbles it up.

But hang on: isn’t this an absurdly anthropomorphic way of describing a biological process? Single cells don’t have minds of their own – so surely they don’t have goals, determination, gusto? When we attribute aims and purposes to these primitive organisms, aren’t we just succumbing to an illusion?

Indeed, you might suspect this is a real-life version of a classic psychology experiment from 1944, which revealed the human impulse to attribute goals and narratives to what we see. When Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel showed people a crudely animated movie featuring a circle and two triangles, most viewers constructed a melodramatic tale of pursuit and rescue – even though they were just observing abstract geometric shapes moving about in space.

Yet is our sense that the macrophage has goals and purpose really just a narrative projection? After all, we can’t meaningfully describe what a macrophage even is without referring to its purpose: it exists precisely to conduct this kind of ‘seek and destroy’ manoeuvre.

More here.

A Culture Canceled

Chris Arnade in American Compass:

The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches.

The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches.

The death of local journalism is at least acknowledged by those involved in the debate as a problem. They are rightly concerned that smaller local newspapers being replaced by far away conglomerates hurts “left-behind” communities since it closes a forum where their issues could be heard, elevated, and addressed.

Getting less attention is the death of churches and unions. Lower income neighborhoods are littered with boarded up versions of both, a result of America’s embrace of a noxious mix of centralized economic power and de-centralized personal freedom.

Both are essential in giving power to the working class, providing them communities where they can go to be heard, and have any needs acknowledged, and perhaps brought to a higher authority to be solved.

More here.

Michael Sandel: The Tyranny of Merit

Seigneur Moments: On Martin Amis

Kevin Power at the Dublin Review of Books:

“There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction).

“There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction).

more here.

The Story of Joy Division

Pippa Bailey at The New Statesman:

The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”.

The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”.

Transmissions takes in Factory Records, Unknown Pleasures, Ian Curtis’s suicide and the Haçienda, with interviews from Peter Hook, Stephen Morris, Bernard Sumner and others. It’s a story about Manchester, too, given authenticity by Peake’s Mancunian accent. (“There is a wilfulness in the psyche of Manchester,” says Peter Saville, and I imagine Andy Burnham nodding furiously.) For those who know this story well, there’s little new here, but it’s a joy all the same.

more here.

Joy Division – Unknown Pleasures 1979

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vUDCZ6NePg&ab_channel=GermanLGonz%C3%A1lezA

When I Step Outside, I Step Into a Country of Men Who Stare

Fatima Bhojani in The New York Times:

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence.

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence.

…This country fails its women from the very top of government leadership to those who live with us in our homes. In September, a woman was raped beside a major highway near Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city. Around 1 a.m., her car ran out of fuel. She called the police and waited. Two armed men broke through the windows and assaulted her in a nearby field. The most senior police official in Lahore remarked that the survivor was assaulted because, he assumed, she “was traveling late at night without her husband’s permission.” An elderly woman in my apartment building in Islamabad, remarked, “Apni izzat apnay haath mein” — Your honor is in your own hands. In Pakistan, sexual assault comes with stigma, the notion that a woman by being on the receiving end of a violent crime has brought shame to herself and her family. Societal judgment is a major reason survivors don’t come forward. Responding to the Lahore assault, Prime Minister Imran Khan proposed chemical castration of the rapists. His endorsement of archaic punishments rather than a sincere promise to undertake the difficult, lengthy and necessary work of reforming criminal and legal procedures is part of the problem. The conviction rate for sexual assault is around 3 percent, according to War Against Rape, a local nonprofit.

More here.

Should America Still Police the World?

Daniel Immerwahr in The New Yorker:

Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “From the Shadows,” and that is an apt description of where Gates has comfortably resided. He is not a flashy man—a colleague once likened him to “the guy at P. C. Richards who sold microwave ovens”—but he has been for decades a quietly persistent presence in foreign policymaking. Gates has served as the Defense Secretary, C.I.A. chief, and deputy national-security adviser, among other roles. Unusually, he has occupied high positions under both Democratic and Republican Presidents. After George W. Bush placed him in charge of the Defense Department, Barack Obama kept him there as a trusted source of counsel. He has called Biden “a man of genuine integrity” and Trump “unfit to be Commander-in-Chief.”

Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “From the Shadows,” and that is an apt description of where Gates has comfortably resided. He is not a flashy man—a colleague once likened him to “the guy at P. C. Richards who sold microwave ovens”—but he has been for decades a quietly persistent presence in foreign policymaking. Gates has served as the Defense Secretary, C.I.A. chief, and deputy national-security adviser, among other roles. Unusually, he has occupied high positions under both Democratic and Republican Presidents. After George W. Bush placed him in charge of the Defense Department, Barack Obama kept him there as a trusted source of counsel. He has called Biden “a man of genuine integrity” and Trump “unfit to be Commander-in-Chief.”

Gates’s latest book, “Exercise of Power,” offers a stark view of the world. The country is “challenged on every front,” Gates believes. The places the United States must police are, in his various descriptions, a “bane” (Iran), a “curse” (Iraq), a “primitive country” (Afghanistan), and a “sinkhole of conflict and terrorism” (the Middle East). Its adversaries form a rogue’s gallery of “bad guys,” “thugs,” “serial cheaters and liars,” and “ever-duplicitous Pakistanis.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Untitled

Lord,

……… when you send the rain,

……… think about it, please,

……… a little?

Do

……… not get carried away

……… by the sound of falling water,

……… the marvelous light

……… on the falling water.

I

……… am beneath that water.

……… It falls with great force

……… and the light

Blinds

……… me to the light.

by James Baldwin – 1924-1987

Tuesday, November 17, 2020

Buster Keaton Falls Up

John Plotz in Public Books:

Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.

Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.

Keaton is remembered now as a brilliant stuntman and inventor of trick shots (see, for instance, the cutaway walls of the house in 1921’s The High Sign). However, his true genius resides in his delightful disorientation from—and re-orientation to—a world that is never quite what he takes it to be.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Lisa Feldman Barrett on Emotions, Actions, and the Brain

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

More here.

Huawei, 5G, and the Man Who Conquered Noise

Steven Levy in Wired:

ERDAL ARIKAN was born in 1958 and grew up in Western Turkey, the son of a doctor and a homemaker. He loved science. When he was a teenager, his father remarked that, in his profession, two plus two did not always equal four. This fuzziness disturbed young Erdal; he decided against a career in medicine. He found comfort in engineering and the certainty of its mathematical outcomes. “I like things that have some precision,” he says. “You do calculations and things turn out as you calculate it.”

ERDAL ARIKAN was born in 1958 and grew up in Western Turkey, the son of a doctor and a homemaker. He loved science. When he was a teenager, his father remarked that, in his profession, two plus two did not always equal four. This fuzziness disturbed young Erdal; he decided against a career in medicine. He found comfort in engineering and the certainty of its mathematical outcomes. “I like things that have some precision,” he says. “You do calculations and things turn out as you calculate it.”

Arıkan entered the electrical engineering program at Middle East Technical University. But in 1977, partway through his first year, the country was gripped by political violence, and students boycotted the university. Arıkan wanted to study, and because of his excellent test scores he managed to transfer to CalTech, one of the world’s top science-oriented institutions, in Pasadena, California. He found the US to be a strange and wonderful country. Within his first few days, he was in an orientation session addressed by legendary physicist Richard Feynman. It was like being blessed by a saint.

More here.