Frances Wilson in New Statesman:

In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

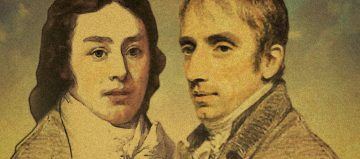

Adam Nicolson makes plain his debt to Richard Holmes: “I think of this book as a tributary to the great Holmesian stream,” he says in the introductory chapter to The Making of Poetry. “Its method is his: to follow in the footsteps of the great, looking to gather the fragments they left on the path, much as Dorothy Wordsworth was seen by an old man as she was accompanying her brother on a walk in the Lake District, keeping ‘close behind him, and she picked up the bits as he let ’em fall, and tak ’em down, and put ’em on paper for him’.” The image of Nicolson as Dorothy, picking up the lines dropped on the road by Wordsworth as he went “bumming and booing” about, is wonderfully apt not least because Nicolson’s own sensibility – his ear, his eye, his sense of place and the intensity of his concentration on words, plants, foliage and light – recalls that of Dorothy Wordsworth. The Making of Poetry is indeed a tributary to the great Holmesian stream, and also a tribute to the Romantic art of observational note-taking.

More here.