Illumina in Nature:

There are more than 120 biobanks worldwide, having evolved over the past 30 years. They range from small, predominantly university-based repositories, to large, government-supported resources. As well as collecting and storing samples, they also provide clinical, pathological, molecular and radiological information for research into personalized medicine. Biobanks allow researchers to explore the causes of disease by helping them link genotypes to phenotypes. This is a process that has been underway for years through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), but it has proved far from straightforward. “What we have learned from GWAS over the last 15 to 20 years is that there are many variants, they have small effect sizes and, even if you total most of the common variants throughout the genome, they account for only a small fraction of phenotypic variance,” says Judy Cho, a translational geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

There are more than 120 biobanks worldwide, having evolved over the past 30 years. They range from small, predominantly university-based repositories, to large, government-supported resources. As well as collecting and storing samples, they also provide clinical, pathological, molecular and radiological information for research into personalized medicine. Biobanks allow researchers to explore the causes of disease by helping them link genotypes to phenotypes. This is a process that has been underway for years through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), but it has proved far from straightforward. “What we have learned from GWAS over the last 15 to 20 years is that there are many variants, they have small effect sizes and, even if you total most of the common variants throughout the genome, they account for only a small fraction of phenotypic variance,” says Judy Cho, a translational geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Biobanks are speeding up progress. They allow researchers to easily analyse increasing numbers of biological samples and associated clinical data to characterize disease mechanisms, find novel drug targets, and identify patients most likely to benefit from a particular treatment approach. “Embedding genomic information in electronic health-care records, so it can be used through the course of life, is an appealing vision,” says Dan Roden, a clinical pharmacologist and Director of the BioVU Biobank at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Tennessee. “But it’s one that is hard to realise; there are lots of logistical problems in creating an infrastructure like that.” BioVU’s step towards achieving this vision is to store DNA extracted from discarded blood, collected during routine clinical testing, linked to de-identified medical records. Around 250,000 DNA samples are now available for Vanderbilt investigators.

But going big isn’t the only solution: insights into common diseases can also be found by analysing smaller disease- and/or ethnic-specific cohorts, which concentrate on important genomic signals. Advances in genetic technologies and increased efforts to capture genetic diversity in biobanks are helping researchers to make robust geno-pheno associations in a cost-effective manner (see ‘Biobanks and geno-pheno associations’).

More here.

Hungary and Poland have vetoed the European Union’s proposed €1.15 trillion ($1.4 trillion) seven-year budget and the €750 billion European recovery fund. Although the two countries are the budget’s biggest beneficiaries, their governments are adamantly opposed to the rule-of-law conditionality that the EU has adopted at the behest of the European Parliament. They know that they are violating the rule of law in egregious ways, and do not want to pay the consequences.

Hungary and Poland have vetoed the European Union’s proposed €1.15 trillion ($1.4 trillion) seven-year budget and the €750 billion European recovery fund. Although the two countries are the budget’s biggest beneficiaries, their governments are adamantly opposed to the rule-of-law conditionality that the EU has adopted at the behest of the European Parliament. They know that they are violating the rule of law in egregious ways, and do not want to pay the consequences.

There’s a passage in Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes in which the French theorist, eyeing his own author photo (turned head, silvered temples, faintly illuminated desk) exclaims: “But I never looked like that!” And yet, how can one know? You are, indeed, “the only one who can never see yourself except as an image” whether that be in the form of a reflection or a photograph. Moreover, one can argue that the author photo is a particularly deceptive sort of image, one that is meant to elicit disparate or even contradictory feelings in the viewer.

There’s a passage in Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes in which the French theorist, eyeing his own author photo (turned head, silvered temples, faintly illuminated desk) exclaims: “But I never looked like that!” And yet, how can one know? You are, indeed, “the only one who can never see yourself except as an image” whether that be in the form of a reflection or a photograph. Moreover, one can argue that the author photo is a particularly deceptive sort of image, one that is meant to elicit disparate or even contradictory feelings in the viewer. If the Australian writer and critic Thelma Forshaw is remembered for anything today, it’s most likely the hatchet job that she gave Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch in 1972. Of the many reviews the book received, Forshaw’s—published in the Age, a newspaper based in Greer’s own hometown of Melbourne—was by far the most disdainful: “King Kong is back. The exploits of the outsized gorilla may have been banned as too scary for kids, but who’s to shield us cowering adults? To increase the terror, the creature now rampaging is a kind of female—a female eunuch. It’s Germ Greer, with a tiny male in her hairy paw (no depilatories) who has been storming round the world knocking over the Empire State Building, scrunching up Big Ben and is now bent on ripping the Sydney Harbour Bridge from its pylons and drinking up the Yarra.” Understandably, Forshaw’s slam piece caused quite a stir, and it was reprinted in a number of papers across the country, often alongside carefully chosen photographs of Greer looking suitably unkempt.

If the Australian writer and critic Thelma Forshaw is remembered for anything today, it’s most likely the hatchet job that she gave Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch in 1972. Of the many reviews the book received, Forshaw’s—published in the Age, a newspaper based in Greer’s own hometown of Melbourne—was by far the most disdainful: “King Kong is back. The exploits of the outsized gorilla may have been banned as too scary for kids, but who’s to shield us cowering adults? To increase the terror, the creature now rampaging is a kind of female—a female eunuch. It’s Germ Greer, with a tiny male in her hairy paw (no depilatories) who has been storming round the world knocking over the Empire State Building, scrunching up Big Ben and is now bent on ripping the Sydney Harbour Bridge from its pylons and drinking up the Yarra.” Understandably, Forshaw’s slam piece caused quite a stir, and it was reprinted in a number of papers across the country, often alongside carefully chosen photographs of Greer looking suitably unkempt.

Once upon a time, Albert Einstein described scientific theories as “free inventions of the human mind.” But in 1980, Stephen Hawking, the renowned Cambridge University cosmologist, had another thought. In a lecture that year, he argued that the so-called Theory of Everything might be achievable, but that the final touches on it were likely to be done by computers. “The end might not be in sight for theoretical physics,” he said. “But it might be in sight for theoretical physicists.” The Theory of Everything is still not in sight, but with computers taking over many of the chores in life — translating languages, recognizing faces, driving cars, recommending whom to date — it is not so crazy to imagine them taking over from the Hawkings and the Einsteins of the world.

Once upon a time, Albert Einstein described scientific theories as “free inventions of the human mind.” But in 1980, Stephen Hawking, the renowned Cambridge University cosmologist, had another thought. In a lecture that year, he argued that the so-called Theory of Everything might be achievable, but that the final touches on it were likely to be done by computers. “The end might not be in sight for theoretical physics,” he said. “But it might be in sight for theoretical physicists.” The Theory of Everything is still not in sight, but with computers taking over many of the chores in life — translating languages, recognizing faces, driving cars, recommending whom to date — it is not so crazy to imagine them taking over from the Hawkings and the Einsteins of the world. Conspiracy theories come in all shapes and sizes, but perhaps the most common form is the Global Cabal theory. A

Conspiracy theories come in all shapes and sizes, but perhaps the most common form is the Global Cabal theory. A  On a mild autumn day in 2016, the Hungarian mathematician

On a mild autumn day in 2016, the Hungarian mathematician  Concern about American democracy is often expressed as a parable of the Thirties: We must prevent another Hitler. The word “fascism” has appeared frequently in denunciations of Donald Trump; many have accused him of a führer-like contempt for the American system. But it is time to ask whether the system itself is not thereby too conveniently excused. Mass political participation has come only recently and reluctantly to America; voter suppression is the more traditional American way. And for reasons that have nothing to do with fascism, even that partial efflorescence may be coming to an end. Trump’s baleful theatrics have distracted us, in fact, from the broader disintegration of the twentieth-century interregnum, of which he is only a symptom. That process has much further to go, and will produce dangers greater than he.

Concern about American democracy is often expressed as a parable of the Thirties: We must prevent another Hitler. The word “fascism” has appeared frequently in denunciations of Donald Trump; many have accused him of a führer-like contempt for the American system. But it is time to ask whether the system itself is not thereby too conveniently excused. Mass political participation has come only recently and reluctantly to America; voter suppression is the more traditional American way. And for reasons that have nothing to do with fascism, even that partial efflorescence may be coming to an end. Trump’s baleful theatrics have distracted us, in fact, from the broader disintegration of the twentieth-century interregnum, of which he is only a symptom. That process has much further to go, and will produce dangers greater than he.

Individual poems by Vilariño have occasionally appeared in anthologies of Latin American poetry in the United States, but not until now, more than a decade after her death and in the centennial year of her birth, has one of her books appeared in English translation. Unsurprisingly, it is her best-known work, Poemas de amor / Love Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), in a translation by the poet Jesse Lee Kercheval. The literary scholar Emir Rodríguez Monegal, a Yale professor who wrote influential treatises on

Individual poems by Vilariño have occasionally appeared in anthologies of Latin American poetry in the United States, but not until now, more than a decade after her death and in the centennial year of her birth, has one of her books appeared in English translation. Unsurprisingly, it is her best-known work, Poemas de amor / Love Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), in a translation by the poet Jesse Lee Kercheval. The literary scholar Emir Rodríguez Monegal, a Yale professor who wrote influential treatises on  Similar to Tony Conrad—who reflected in one of his

Similar to Tony Conrad—who reflected in one of his  There are more than 120 biobanks worldwide, having evolved over the past 30 years. They range from small, predominantly university-based repositories, to large, government-supported resources. As well as collecting and storing samples, they also provide clinical, pathological, molecular and radiological information for research into personalized medicine. Biobanks allow researchers to explore the causes of disease by helping them link genotypes to phenotypes. This is a process that has been underway for years through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), but it has proved far from straightforward. “What we have learned from GWAS over the last 15 to 20 years is that there are many variants, they have small effect sizes and, even if you total most of the common variants throughout the genome, they account for only a small fraction of phenotypic variance,” says Judy Cho, a translational geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

There are more than 120 biobanks worldwide, having evolved over the past 30 years. They range from small, predominantly university-based repositories, to large, government-supported resources. As well as collecting and storing samples, they also provide clinical, pathological, molecular and radiological information for research into personalized medicine. Biobanks allow researchers to explore the causes of disease by helping them link genotypes to phenotypes. This is a process that has been underway for years through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), but it has proved far from straightforward. “What we have learned from GWAS over the last 15 to 20 years is that there are many variants, they have small effect sizes and, even if you total most of the common variants throughout the genome, they account for only a small fraction of phenotypic variance,” says Judy Cho, a translational geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. IF YOU’VE ALREADY READ Camus’s The Plague and have been searching for the perfect pre-apocalyptic fiction work to help you navigate our current affairs, this book may be just the provocation. I opened it knowing little about the author, other than having seen him act in the independent feature The War Within and perused his play Disgraced. Neither had prepared me for Homeland Elegies, which turns out to be masterful storytelling for these disturbing times.

IF YOU’VE ALREADY READ Camus’s The Plague and have been searching for the perfect pre-apocalyptic fiction work to help you navigate our current affairs, this book may be just the provocation. I opened it knowing little about the author, other than having seen him act in the independent feature The War Within and perused his play Disgraced. Neither had prepared me for Homeland Elegies, which turns out to be masterful storytelling for these disturbing times. Letting the virus that causes Covid-19 circulate more-or-less freely is dangerous not only because it risks overwhelming hospitals and so endangering lives unnecessarily, but also because it could delay the evolution of the virus to a more benign form and potentially even make it more lethal.

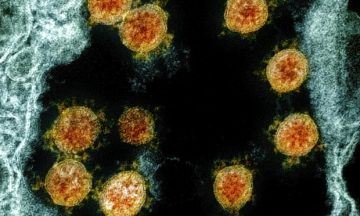

Letting the virus that causes Covid-19 circulate more-or-less freely is dangerous not only because it risks overwhelming hospitals and so endangering lives unnecessarily, but also because it could delay the evolution of the virus to a more benign form and potentially even make it more lethal. As picks for President-elect Joe Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) transition team were announced, I felt concerned and disheartened about

As picks for President-elect Joe Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) transition team were announced, I felt concerned and disheartened about