A panel discussion of Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel Ministry for the Future with Naomi Klein, Cymie Payne, and Jorge Marcone, moderated by climate scientist Robert Kopp:

Category: Recommended Reading

Development, Growth, Power

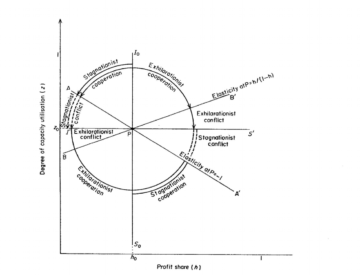

Maya Adereth interviews Amit Bhaduri in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth interviews Amit Bhaduri in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth: The occasion for this interview was a reflection on the breakdown of social democracy. Why don’t we start there?

Amit Bhaduri: In order to understand the breakdown of social democracy, we need to start with its prehistory. In the 1850s, Marx was convinced that if universal suffrage were granted it would spell the end of capitalism. He reasoned that as numerically the largest class in society, workers would dismantle it if given the chance. You also had members of the British Parliament like Lord Cecil, who argued that universal suffrage would mean the end of private property. We know, of course, that neither of these predictions came to pass—the proletariat never came to compose an absolute majority of the population, and private property persisted in spite of universal suffrage. The important inference to draw from this, and from the development of capitalism throughout the twentieth century, is that as a system, capitalism is far more capable of accommodating political change than economic change. General strikes, as powerful as they might be, have never been able to fundamentally alter the structure of property relations under capitalist society. Meanwhile political rights like suffrage were granted, and, progressively, expanded first across the Global North, and then gradually to many countries in the South.

More here.

Paul Celan – Allerseelen / All Souls

Albert Pinkham Ryder: Isolato of The Brush

Andrew L. Shea at The New Criterion:

In one of his only published comments on art, a 1905 treatise titled “Paragraphs from the Studio of a Recluse,” the American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) wrote that “the artist needs but a roof, a crust of bread, and his easel, and all the rest God gives him in abundance.” Ryder continued: “He must live to paint and not paint to live. He cannot be a good fellow; he is rarely a wealthy man, and upon the potboiler is inscribed the epitaph of his art.” A quarter-century later, Virginia Woolf struck a similar note when she famously argued that a woman wanting to write fiction requires just two things: enough money to get by on, and a “room of one’s own.” In context, the two essays aren’t at all alike: Woolf’s broader argument is about making space for women in the literary tradition, whereas Ryder offers a personal defense of thrift and simplicity. Shared by both, however, is the understanding that isolation is a positive and essential—perhaps the essential—condition for artistic creation. A room “of one’s own,” that is—the studio of a recluse.

In one of his only published comments on art, a 1905 treatise titled “Paragraphs from the Studio of a Recluse,” the American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) wrote that “the artist needs but a roof, a crust of bread, and his easel, and all the rest God gives him in abundance.” Ryder continued: “He must live to paint and not paint to live. He cannot be a good fellow; he is rarely a wealthy man, and upon the potboiler is inscribed the epitaph of his art.” A quarter-century later, Virginia Woolf struck a similar note when she famously argued that a woman wanting to write fiction requires just two things: enough money to get by on, and a “room of one’s own.” In context, the two essays aren’t at all alike: Woolf’s broader argument is about making space for women in the literary tradition, whereas Ryder offers a personal defense of thrift and simplicity. Shared by both, however, is the understanding that isolation is a positive and essential—perhaps the essential—condition for artistic creation. A room “of one’s own,” that is—the studio of a recluse.

more here.

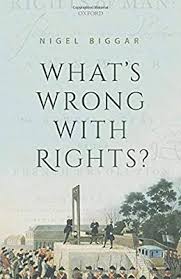

What’s Wrong with Rights?

Michael Ignatieff at Literary Review:

There’s plenty wrong with rights, Nigel Biggar tells us, as some very powerful thinkers have been saying since the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’ first entered the lexicon of mass democratic politics during the French Revolution. This sceptical tradition has been particularly strong in Britain, a country that likes to think it invented rights at Runnymede. It runs from Edmund Burke, through Jeremy Bentham (who called natural rights ‘nonsense on stilts’) right up to contemporary figures like Jonathan Sumption, a former justice of the UK Supreme Court, and the philosopher Onora O’Neill.

There’s plenty wrong with rights, Nigel Biggar tells us, as some very powerful thinkers have been saying since the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’ first entered the lexicon of mass democratic politics during the French Revolution. This sceptical tradition has been particularly strong in Britain, a country that likes to think it invented rights at Runnymede. It runs from Edmund Burke, through Jeremy Bentham (who called natural rights ‘nonsense on stilts’) right up to contemporary figures like Jonathan Sumption, a former justice of the UK Supreme Court, and the philosopher Onora O’Neill.

Biggar, a professor of theology and ethics at Oxford University, gives us a powerfully reasoned intellectual history of the sceptical tradition from the 1780s to the present day. He’s a discriminating guide rather than an anti-rights ideologist, and his analysis of these traditions is intricate, exacting and fair.

more here.

Inventing the authority of a modern self

Daniel Mahoney in The New Criterion:

The distinguished contemporary French political philosopher Pierre Manent has spent four decades chronicling the development of modern self-consciousness, including the flight from human nature and “the moral contents of life” that define modern self-understanding in its most radical forms. Manent’s work combines penetrating analyses of great works of political, philosophical, and religious reflection with judicious independent thought. In both, he illumines the interpenetration of politics and the things of the soul. That dialectical melding of politics and soul permanently defines the human condition, even in the most remote times and climes.

The distinguished contemporary French political philosopher Pierre Manent has spent four decades chronicling the development of modern self-consciousness, including the flight from human nature and “the moral contents of life” that define modern self-understanding in its most radical forms. Manent’s work combines penetrating analyses of great works of political, philosophical, and religious reflection with judicious independent thought. In both, he illumines the interpenetration of politics and the things of the soul. That dialectical melding of politics and soul permanently defines the human condition, even in the most remote times and climes.

Manent continues that work with learning and grace in Montaigne: Life without Law.1 Montaigne (1533–92) is much more than a literary figure for Manent. His Montaigne is first and foremost a philosopher and a moral reformer, even a founder of one vitally important strain of modern self-understanding. In this new form of consciousness, human beings take their bearing neither from great models of heroism or sanctity or wisdom, nor from natural and divine law. Rather, Montaigne asks his readers to eschew self-transcending admiration for others, no matter how exemplary great souls may seem to be. He wishes those who follow him to reject the path of repentance for sins, and to bow before the demands and requirements of one’s unique self, what he calls one’s “master-form.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

Thank Heavens for Shakespeare

I am always in and out of love

with my husband. Tonight—out.

Out of love and instead, in a cranky mood:

That sweatshirt he’s wearing, and his hair!

Maybe Titania and Oberon were out of love and needed an excellent fight.

Of course, here I am in my own drab grey sweatshirt, no sleeping beauty

amid wood thyme and nodding oxlips.

Where is my night full of misguided agents—

to light my eyes on fire with a love gone wrong—some strange fellow

(who, shhhh, is actually my husband now in full hunk-mode) to call me

angel.

And we find our way through a wood full of word play and misunder-

standings

to a magical morning where the sun is tender and my husband is new and

yet

the same to me again, and my own skin radiant, my hair long and shiny.

Love undeniable.

Oh, Husband of the Ill-Fitting Sweatshirt! Let me pour you a glass of this

most

mysterious wine I’ve found hidden in a dusty cupboard.

Let us go outside and wander in our familiar backyard, barefoot.

Let us recognize that even those luminous stars

must sometimes feel stuck in their very own heaven.

by Carol Berg

from Decomp Magazine

The Social Life of Forests

Ferris Jabr in The New York Times:

By the time she was in grad school at Oregon State University, however, Simard understood that commercial clearcutting had largely superseded the sustainable logging practices of the past. Loggers were replacing diverse forests with homogeneous plantations, evenly spaced in upturned soil stripped of most underbrush. Without any competitors, the thinking went, the newly planted trees would thrive. Instead, they were frequently more vulnerable to disease and climatic stress than trees in old-growth forests. In particular, Simard noticed that up to 10 percent of newly planted Douglas fir were likely to get sick and die whenever nearby aspen, paper birch and cottonwood were removed. The reasons were unclear. The planted saplings had plenty of space, and they received more light and water than trees in old, dense forests. So why were they so frail?

Simard suspected that the answer was buried in the soil. Underground, trees and fungi form partnerships known as mycorrhizas: Threadlike fungi envelop and fuse with tree roots, helping them extract water and nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen in exchange for some of the carbon-rich sugars the trees make through photosynthesis. Research had demonstrated that mycorrhizas also connected plants to one another and that these associations might be ecologically important, but most scientists had studied them in greenhouses and laboratories, not in the wild. For her doctoral thesis, Simard decided to investigate fungal links between Douglas fir and paper birch in the forests of British Columbia. Apart from her supervisor, she didn’t receive much encouragement from her mostly male peers. “The old foresters were like, Why don’t you just study growth and yield?” Simard told me. “I was more interested in how these plants interact. They thought it was all very girlie.”

More here.

Friday, December 4, 2020

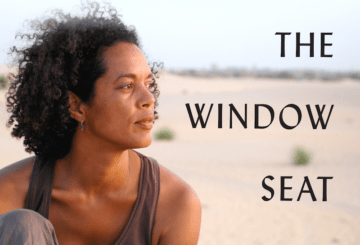

Aminatta Forna and Maaza Mengiste: A Conversation

From Literary Hub:

Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in The Window Seat, Aminatta Forna’s debut collection of essays, which Grove/Atlantic publishes in May next year. As a reporter and traveler, Forna has been studying flight and movement for her entire life. She has also lived in its wake. Just as Barack Obama, Sr. departed Kenya for America for an education, Forna’s own father left Sierra Leone to study medicine abroad.

Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in The Window Seat, Aminatta Forna’s debut collection of essays, which Grove/Atlantic publishes in May next year. As a reporter and traveler, Forna has been studying flight and movement for her entire life. She has also lived in its wake. Just as Barack Obama, Sr. departed Kenya for America for an education, Forna’s own father left Sierra Leone to study medicine abroad.

Raised between countries, with a front row seat to ruptures of history, Forna muses here on what it means to live in a world shaped by travel of choice and necessity. How to appreciate the wonders of flight while also acknowledging the terror which prompts less metaphorical flight. As the child of a doctor, who one day wanted to be a veterinarian, Forna also returns such questions to the biosphere. What does the way we treat animals and landscapes say of our capacity to share any space? How will we ever appreciate the gulf that stands between us and every other species, for whom migration is often crucial to survival?

Recently, Forna spoke over email with novelist and friend Maaza Mengiste, whose latest book, The Shadow King, was a finalist for the 2020 Booker Prize.

More here.

Light-based Quantum Computer Exceeds Fastest Classical Supercomputers

Daniel Garisto in Scientific American:

For the first time, a quantum computer made from photons—particles of light—has outperformed even the fastest classical supercomputers.

For the first time, a quantum computer made from photons—particles of light—has outperformed even the fastest classical supercomputers.

Physicists led by Chao-Yang Lu and Jian-Wei Pan of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in Shanghai performed a technique called Gaussian boson sampling with their quantum computer, named Jiŭzhāng. The result, reported in the journal Science, was 76 detected photons—far above and beyond the previous record of five detected photons and the capabilities of classical supercomputers.

Unlike a traditional computer built from silicon processors, Jiŭzhāng is an elaborate tabletop setup of lasers, mirrors, prisms and photon detectors. It is not a universal computer that could one day send e-mails or store files, but it does demonstrate the potential of quantum computing.

Last year, Google captured headlines when its quantum computer Sycamore took roughly three minutes to do what would take a supercomputer three days (or 10,000 years, depending on your estimation method). In their paper, the USTC team estimates that it would take the Sunway TaihuLight, the third most powerful supercomputer in the world, a staggering 2.5 billion years to perform the same calculation as Jiŭzhāng.

More here. And more in Science News here.

Adam Smith’s Other Masterwork

Ryan P. Hanley in the National Review:

Adam Smith is today known as the founding father of economics. But by profession he was a university professor, holding a chair in moral philosophy. It was in this capacity that in 1759 he published the first of his two books. Neither can be fully appreciated without the other — and both deserve our careful attention now, perhaps more than ever.

Adam Smith is today known as the founding father of economics. But by profession he was a university professor, holding a chair in moral philosophy. It was in this capacity that in 1759 he published the first of his two books. Neither can be fully appreciated without the other — and both deserve our careful attention now, perhaps more than ever.

Smith’s first book was The Theory of Moral Sentiments. An instant hit, it early on caught the attention of such prominent admirers as Edmund Burke, David Hume, and John Adams. The aim of the book is at once descriptive and prescriptive. It is descriptive insofar as it provides an account of the moral institutions that enable a free society to function. And it is prescriptive insofar as it seeks to cultivate the qualities of character that allow free individuals to lead flourishing lives and free societies to prosper and persist.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments covers a great deal of ground, tackling topics ranging from justice and judgment to conscience and love. But its most original and important contributions arguably come on three specific fronts: its theory of sympathy, its concept of the impartial spectator, and its vision of virtue.

More here.

Amorphous Flocks of Starlings Swell Above Danish Marshlands

Friday Poem

Things That Happen in an Eclipse

I’m lying on my back on a blanket in the front yard, and I have my glasses and my dog.

My next-door neighbor is out front, too, on his porch, talking to some other neighbors who have walked over, but I can’t hear what they’re saying.

He is an old man. I sit up and call over to him, ask him if he has seen it yet.

No way. I’m not going out in that heat, he says, holding his white paper glasses.

I smile and say okay and lie down again.

I can feel earrings on my neck and the mulch of the flowerbed on the back of my head. The flowerbed needs weeding.

My dog pants, and I pet her.

I watch. Sometimes I check the time: maximum eclipse at 2:41 p.m. Just partial, but still.

There is the occasional passing car. I wonder if they mind that they’re missing it.

Beyond my glasses are the shaded sky and the carpenter bees that put holes in my porch.

Wind chimes and cicadas, the sense of a shift.

Nothing is happening, nothing that I can see, without the glasses. Only in the glasses, it is happening.

I watch. Once, I hit my glasses accidentally, and for a second there is the sun, and I wonder if I will go blind but decide not to worry about it.

Now I know that I think of people in eclipses. Maybe this is what eclipses do. Maybe because you are under a thing you have never seen before, you think of things you have seen and known.

The sun becomes the moon and the moon becomes nothing, like thoughts passing over one another, on their way somewhere else.

by Susan Harlan

from The Brooklyn Quarterly

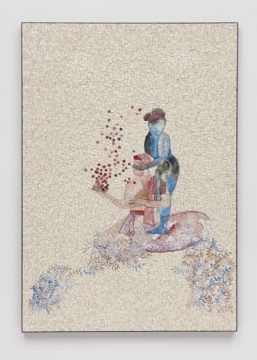

Venus and the Devata

From The Paris Review:

Shahzia Sikander’s first New York solo exhibition in more than a decade showcases an astonishing range of work: paintings, mosaics, animations, and her inaugural foray into freestanding sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies, a stunning monument to desire that depicts both a Greco-Roman goddess and an Indian devata. Sikander is an artist whose talents and ambitions threaten to outstrip the materials available to her; the works featured here confront the climate crisis, religion, migration, war, memory, and much more. But despite the daunting abundance of ideas and mediums, careful attention reveals that the show itself is a sort of mosaic, the pieces all slotting into place to form a portrait of the artist over the past few years of her practice. The works on paper inform the animations; the animations inform the individual mosaics (in part, Sikander credits her experiments with the latter form to “the dynamism of the pixel that emerged in my mind as a parallel to the unit of a mosaic”).

Shahzia Sikander’s first New York solo exhibition in more than a decade showcases an astonishing range of work: paintings, mosaics, animations, and her inaugural foray into freestanding sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies, a stunning monument to desire that depicts both a Greco-Roman goddess and an Indian devata. Sikander is an artist whose talents and ambitions threaten to outstrip the materials available to her; the works featured here confront the climate crisis, religion, migration, war, memory, and much more. But despite the daunting abundance of ideas and mediums, careful attention reveals that the show itself is a sort of mosaic, the pieces all slotting into place to form a portrait of the artist over the past few years of her practice. The works on paper inform the animations; the animations inform the individual mosaics (in part, Sikander credits her experiments with the latter form to “the dynamism of the pixel that emerged in my mind as a parallel to the unit of a mosaic”).

More here.

Reversal of biological clock restores vision in old mice

Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Ageing affects the body in myriad ways — among them, adding, removing or altering chemical groups such as methyls on DNA. These ‘epigenetic’ changes accumulate as a person ages, and some researchers have proposed tracking the changes as a way of calibrating a molecular clock to measure biological age, an assessment that takes into account biological wear-and-tear and can differ from chronological age. That has raised the possibility that epigenetic changes contribute to the effects of ageing. “We set out with a question: if epigenetic changes are a driver of ageing, can you reset the epigenome?” says David Sinclair, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the Nature study. “Can you reverse the clock?”

Ageing affects the body in myriad ways — among them, adding, removing or altering chemical groups such as methyls on DNA. These ‘epigenetic’ changes accumulate as a person ages, and some researchers have proposed tracking the changes as a way of calibrating a molecular clock to measure biological age, an assessment that takes into account biological wear-and-tear and can differ from chronological age. That has raised the possibility that epigenetic changes contribute to the effects of ageing. “We set out with a question: if epigenetic changes are a driver of ageing, can you reset the epigenome?” says David Sinclair, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the Nature study. “Can you reverse the clock?”

There were suggestions that the approach could work: in 2016, Belmonte and his colleagues reported2 the effects of expressing four genes in mice genetically engineered to age more rapidly than normal. It was already known that triggering these genes could cause cells to lose their developmental identity — the features that make, for example, a skin cell look and behave like a skin cell — and revert to a stem-cell like state. But rather than turn the genes on and leave them that way, Belmonte’s team turned them on for only a few days, then switched them off again, in the hope of reverting cells to a ‘younger’ state without erasing their identity.

The result was mice that aged more slowly, and had a pattern of epigenetic marks indicative of younger animals.

More here.

Slowdive – Souvlaki – Pitchfork Classic

Candy (1968) Richard Burton

Terry Southern’s Lucid Absurdities

Eric Been at JSTOR Daily:

Southern contained multitudes: He was a first-rate screenwriter, novelist, essayist, cultural tastemaker, critic, craftsman of the weird short-story, and a devotee of letter-writing (a mode he once called “the purest form of writing there is… because it’s writing to an audience of one”). One of Southern’s touchstones was the notion of the grotesque—he wanted to examine what disturbed people, pushing a macabre-showing mirror back in his audience’s face, and to muck through the modern American “freak show” at large.

Born in the cotton-farming town of Alvarado, Texas, in 1924, Southern went on to become a U.S. Army demolitions expert in World War II. After earning an English degree at Northwestern University, he subsequently studied philosophy in Paris at the Sorbonne, via the G.I. Bill. In France, after finishing up at school in the early fifties, Southern stayed in the Latin Quarter for a stint—enticed by existentialism, the city’s jazz scene, and the literary crowd he fell into.

more here.

On Don Mee Choi’s “DMZ Colony”

Jae Kim at the LARB:

When asked in an interview with Words Without Borders to give an example of an untranslatable word in Korean, Choi answers that duplicatives, “adverbs or adjectives that are repeated to form a pair,” poses a challenge. “Such doubling is the norm in Korean, and it accentuates the sounds, which can also have the phonetic or mimetic effects of onomatopoeia.” Her solution is often to use a similar tactic in English, such as “swarmsswarms” or “waddlewaddling.” In “Orphan Kim Seong-rye,” she uses the doubling technique twice: “Oblong oblong” and “circled and circled.” While the latter sounds natural in English, the former is more difficult to digest. It demands the reader’s attention, and the reader lingers over the phrase — oblong oblong, oblong oblong… — until all that remains is the sound.

When asked in an interview with Words Without Borders to give an example of an untranslatable word in Korean, Choi answers that duplicatives, “adverbs or adjectives that are repeated to form a pair,” poses a challenge. “Such doubling is the norm in Korean, and it accentuates the sounds, which can also have the phonetic or mimetic effects of onomatopoeia.” Her solution is often to use a similar tactic in English, such as “swarmsswarms” or “waddlewaddling.” In “Orphan Kim Seong-rye,” she uses the doubling technique twice: “Oblong oblong” and “circled and circled.” While the latter sounds natural in English, the former is more difficult to digest. It demands the reader’s attention, and the reader lingers over the phrase — oblong oblong, oblong oblong… — until all that remains is the sound.

more here.

Thursday, December 3, 2020

Don DeLillo’s “The Silence”

Tess McNulty in The Point:

Flip through Don DeLillo’s massive corpus, and you may notice that the word “silence” crops up, again and again, at crucial moments. It’s the first word he spoke to the public when, in 1982, he gave his first, reluctant interview. Why, asked the critic Tom LeClair, did DeLillo shun the public eye? “Silence, exile, cunning, and so on,” the author responded, quoting Stephen Dedalus, tongue in cheek. It’s a word that then wended through his work, uttered by his secretive, mysterious men—“Silence,” says Underworld’s Nick Shay, “is the condition you accept as a judgment on your crimes.” It’s a word that, finally, became the target of his most serious critic, James Wood. Far from quiet, Wood complained in a 2000 essay, DeLillo’s books simply could not shut up. Underworld in particular—his vast 1997 Cold War epic—seemed gripped by the delusion that it “might never have to end.” “There are many enemies, seen and unseen, in Underworld,” wrote Wood, “but silence is not one of them.”

Flip through Don DeLillo’s massive corpus, and you may notice that the word “silence” crops up, again and again, at crucial moments. It’s the first word he spoke to the public when, in 1982, he gave his first, reluctant interview. Why, asked the critic Tom LeClair, did DeLillo shun the public eye? “Silence, exile, cunning, and so on,” the author responded, quoting Stephen Dedalus, tongue in cheek. It’s a word that then wended through his work, uttered by his secretive, mysterious men—“Silence,” says Underworld’s Nick Shay, “is the condition you accept as a judgment on your crimes.” It’s a word that, finally, became the target of his most serious critic, James Wood. Far from quiet, Wood complained in a 2000 essay, DeLillo’s books simply could not shut up. Underworld in particular—his vast 1997 Cold War epic—seemed gripped by the delusion that it “might never have to end.” “There are many enemies, seen and unseen, in Underworld,” wrote Wood, “but silence is not one of them.”

White Noise was DeLillo’s breakout book, his first—in 1985—to inspire loud chatter. “Postmodernism, Postmodernism!” the critics all cried, as the author ran his twelve-year-long victory lap, publishing Libra, Mao II and then Underworld to resounding applause. These, the 1980s and 1990s, were the decades of DeLillo’s canonization.

More here.

As a child, Suzanne Simard often roamed Canada’s old-growth forests with her siblings, building forts from fallen branches, foraging mushrooms and huckleberries and occasionally eating handfuls of dirt (she liked the taste). Her grandfather and uncles, meanwhile, worked nearby as horse loggers, using low-impact methods to selectively harvest cedar, Douglas fir and white pine. They took so few trees that Simard never noticed much of a difference. The forest seemed ageless and infinite, pillared with conifers, jeweled with raindrops and brimming with ferns and fairy bells. She experienced it as “nature in the raw” — a mythic realm, perfect as it was. When she began attending the University of British Columbia, she was elated to discover forestry: an entire field of science devoted to her beloved domain. It seemed like the natural choice.

As a child, Suzanne Simard often roamed Canada’s old-growth forests with her siblings, building forts from fallen branches, foraging mushrooms and huckleberries and occasionally eating handfuls of dirt (she liked the taste). Her grandfather and uncles, meanwhile, worked nearby as horse loggers, using low-impact methods to selectively harvest cedar, Douglas fir and white pine. They took so few trees that Simard never noticed much of a difference. The forest seemed ageless and infinite, pillared with conifers, jeweled with raindrops and brimming with ferns and fairy bells. She experienced it as “nature in the raw” — a mythic realm, perfect as it was. When she began attending the University of British Columbia, she was elated to discover forestry: an entire field of science devoted to her beloved domain. It seemed like the natural choice.