Category: Recommended Reading

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: David Stasavage on the Origin and History of Democracy

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Those of us living in democracies tend to take the idea for granted. We forget what an audacious, radical idea it is to put government power into the hands of literally all of the citizens of a country. Where did such an idea come from, and where is it going? Political scientist David Stasavage has written an ambitious history of democracy worldwide, in which he makes a number of unconventional points. The roots of democracy go much further back than we often think; the idea wasn’t invented in Athens, but can be found in a large number of ancient societies. And the resurgence of democracy in Europe wasn’t because that continent was especially advanced, but precisely the opposite. These insights have implications for what the future of democracy has in store.

Those of us living in democracies tend to take the idea for granted. We forget what an audacious, radical idea it is to put government power into the hands of literally all of the citizens of a country. Where did such an idea come from, and where is it going? Political scientist David Stasavage has written an ambitious history of democracy worldwide, in which he makes a number of unconventional points. The roots of democracy go much further back than we often think; the idea wasn’t invented in Athens, but can be found in a large number of ancient societies. And the resurgence of democracy in Europe wasn’t because that continent was especially advanced, but precisely the opposite. These insights have implications for what the future of democracy has in store.

More here.

The Stay At Home Museum: Bruegel

App: Ovia Pregnancy Tracker

Kea Krause at The Believer:

![]() At twenty-seven weeks, my baby was a sweet potato—and also a croissant, a slingshot, and a sugar glider. At thirty-one weeks, she was a head of romaine lettuce, a croquembouche, a foam finger, and a small-clawed otter. There were inconsistencies. At twenty-four weeks, she was the size of an Atlantic puffin but also a GI Joe, which I’d thought was very small. The bakery item that week was a demi-baguette, which further complicated things, as a baguette is long and skinny, unlike a rotund Arctic bird. Later, I realized I had confused the GI Joe with a toy soldier. (I myself had been a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles girl in childhood.) Some weeks I tried to average out the animal, vegetable, toy, and bread and come up with my own Jabberwocky: a puffin with baguette legs and a GI Joe head.

At twenty-seven weeks, my baby was a sweet potato—and also a croissant, a slingshot, and a sugar glider. At thirty-one weeks, she was a head of romaine lettuce, a croquembouche, a foam finger, and a small-clawed otter. There were inconsistencies. At twenty-four weeks, she was the size of an Atlantic puffin but also a GI Joe, which I’d thought was very small. The bakery item that week was a demi-baguette, which further complicated things, as a baguette is long and skinny, unlike a rotund Arctic bird. Later, I realized I had confused the GI Joe with a toy soldier. (I myself had been a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles girl in childhood.) Some weeks I tried to average out the animal, vegetable, toy, and bread and come up with my own Jabberwocky: a puffin with baguette legs and a GI Joe head.

more here.

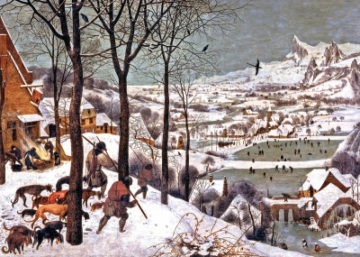

Bruegel as Cinema

Jackson Arn at Art in America:

BRUEGEL SEEMS LIKE A BETTER FIT for a certain type of film than for poetry. His indiscriminate eye; his contempt for obvious “takeaways”; his wide, lucid images withholding judgment—in all these ways, he anticipates the “slow cinema” of the last few decades. It seems appropriate that director Andrei Tarkovsky, a pivotal figure in the flourishing of this kind of cinema, should be the first major filmmaker to put Hunters to work onscreen.

BRUEGEL SEEMS LIKE A BETTER FIT for a certain type of film than for poetry. His indiscriminate eye; his contempt for obvious “takeaways”; his wide, lucid images withholding judgment—in all these ways, he anticipates the “slow cinema” of the last few decades. It seems appropriate that director Andrei Tarkovsky, a pivotal figure in the flourishing of this kind of cinema, should be the first major filmmaker to put Hunters to work onscreen.

Tarkovsky left behind two unmistakable Hunters homages, one a long, aching look at the image and the other a bizarre, fractured tableau vivant. Even if he’d shot neither, people would compare his work to Bruegel’s. Andrei Rublev (1966) opens with one of the most Bruegel-esque scenes ever filmed: medieval peasants build a hot air balloon, launch it with one of their number tied beneath, and hoot with delight as he floats off over the countryside before crashing Icarus-like to earth. The scene ends with a zoom shot of the ground—Tarkovsky, like Bruegel, is always looking down at his figures, so that they don’t seem to reach up to the heavens so much as sink into the mud.

more here.

How Mira Nair Made Her Own “Suitable Boy”

Isaac Chotiner in The New Yorker:

This month marks the American release of the director Mira Nair’s six-part television adaptation of “A Suitable Boy,” Vikram Seth’s beloved, kaleidoscopic novel of early post-Partition India, from 1993. (It began streaming on Acorn TV on December 7th.) The book, which, at more than thirteen hundred pages, is longer than “War and Peace,” tells the story of a young woman, Lata, and her search for a husband, while also featuring a remarkable cast of characters, largely from four interwoven families. The novel also touches on land reform, cricket, and religious tension, in playful, inventive language and sometimes with laugh-out-loud humor. Seth reportedly has been working on a sequel for more than a decade, the rumors of which have thrilled his fans.

This month marks the American release of the director Mira Nair’s six-part television adaptation of “A Suitable Boy,” Vikram Seth’s beloved, kaleidoscopic novel of early post-Partition India, from 1993. (It began streaming on Acorn TV on December 7th.) The book, which, at more than thirteen hundred pages, is longer than “War and Peace,” tells the story of a young woman, Lata, and her search for a husband, while also featuring a remarkable cast of characters, largely from four interwoven families. The novel also touches on land reform, cricket, and religious tension, in playful, inventive language and sometimes with laugh-out-loud humor. Seth reportedly has been working on a sequel for more than a decade, the rumors of which have thrilled his fans.

Nair, who was born in 1957 in the Indian state of Odisha (then called Orissa), and has been based in New York for about four decades, was an obvious choice for the adaptation. In 1988, she directed “Salaam Bombay!,” a critically acclaimed account of life in the slums of Mumbai. She followed it up with an early Denzel Washington drama, “Mississippi Masala,” about an Indian from Uganda in the American South. Since then, Nair has made ten feature films, including “Monsoon Wedding,” from 2001, and has become known as one of the preëminent interpreters of the Indian-immigrant experience. Nair has also adapted classic novels, including “Vanity Fair,” and several pieces of modern literature, such as Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake” and Mohsin Hamid’s “The Reluctant Fundamentalist.” In a Profile of Nair, in 2002, John Lahr wrote, “Nair’s films negotiate disparate ethnic geographies with the same kind of sly civility she practices in life. Her approach is sometimes oblique: she doesn’t make political films, but she does make her films politically. Her gift, to which ‘Monsoon Wedding’ attests, is to make diversity irresistible.”

Nair and I recently spoke over Zoom, while she was completing work on the last episode of the series. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed her career as a filmmaker, the challenges of adapting an epic novel, and how rising intolerance in India, led by the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, affected her work on “A Suitable Boy.” After our interview, it was reported that members of the B.J.P. called for an investigation of Netflix, the series’ Indian distributor, claiming that the depiction of a kiss between a Muslim man and Hindu woman intentionally affronts religious sentiments, which in India is a criminal offense. Netflix has made no public comment, and Nair declined to address the complaint.

More here.

Could COVID delirium bring on dementia?

Carrie Arnold in Nature:

In her job as a physician at the Boston Medical Center in Massachusetts, Sondra Crosby treated some of the first people in her region to get COVID-19. So when she began feeling sick in April, Crosby wasn’t surprised to learn that she, too, had been infected. At first, her symptoms felt like those of a bad cold, but by the next day, she was too sick to get out of bed. She struggled to eat and depended on her husband to bring her sports drinks and fever-reducing medicine. Then she lost track of time completely.

In her job as a physician at the Boston Medical Center in Massachusetts, Sondra Crosby treated some of the first people in her region to get COVID-19. So when she began feeling sick in April, Crosby wasn’t surprised to learn that she, too, had been infected. At first, her symptoms felt like those of a bad cold, but by the next day, she was too sick to get out of bed. She struggled to eat and depended on her husband to bring her sports drinks and fever-reducing medicine. Then she lost track of time completely.

For five days, Crosby lay in a confused haze, unable to remember the simplest things, such as how to turn on her phone or what her address was. She began hallucinating, seeing lizards on her walls and smelling a repugnant reptilian odour. Only later did Crosby realize that she had had delirium, the formal medical term for her abrupt, severe disorientation. “I didn’t really start processing it until later when I started to come out of it,” she says. “I didn’t have the presence of mind to think that I was anything more than just sick and dehydrated.”

Physicians treating people hospitalized with COVID-19 report that a large number experience delirium, and that the condition disproportionately affects older adults. An April 2020 study in Strasbourg, France, found that 65% of people who were severely ill with coronavirus had acute confusion — a symptom of delirium1. Data presented last month at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians by scientists at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, showed that 55% of the 2,000 people they tracked who were treated for COVID-19 in intensive-care units (ICUs) around the world had developed delirium. These numbers are much higher than doctors are used to: usually, about one-third of people who are critically ill develop delirium, according to a 2015 meta-analysis2 (see ‘How common is delirium?’).

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Woman Unborn

I am not born as yet,

five minutes before my birth.

I can still go back

into my unbirth.

Now it’s ten minutes before,

now, it’s one hour before birth.

I go back,

I run

into my minus life.

I walk through my unbirth as in a tunnel

with bizarre perspectives.

Ten years before,

a hundred and fifty years before,

I walk, my steps thump,

a fantastic journey through epochs

in which there was no me.

How long is my minus life,

nonexistence so much resembles immortality.

Here is Romanticism, where I could have been a spinster,

Here is the Renaissance, where I would have been

an ugly and unloved wife of an evil husband,

The Middle Ages, where I would have carried water in a tavern.

I walk still further,

what an echo,

my steps thump

through my minus life,

through the reverse of life.

I reach Adam and Eve,

nothing is seen anymore, it’s dark.

Now my nonexistence dies already

with the trite death of mathematical fiction.

As trite as the death of my existence would have been

had I been really born.

by Anna Swir

from Talking to My Body,1996

Copper Canyon Press

translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Leonard Nathan.

Sunday, December 6, 2020

Torturing Geniuses

Agnes Callard in The Point:

Beth, the protagonist of the TV show The Queen’s Gambit, is not someone you’d want as a friend. She takes money from her childhood mentor—the old janitor who taught her chess—and never pays him back, visits him or thanks him for launching her career. She treats the young men who help her improve—a group that eventually coalesces into a supportive entourage—in a similarly instrumental way. She is so focused on winning tournaments that she can barely spare a word of caution when her adoptive mother is falling into a fatal alcoholic spiral. When she loses, she is petulant and childish, unlike her opponents, who are graceful and kind. She is cruel and manipulative when—as an adult—she plays against a talented Russian child, softening to him only after she has beaten him.

Beth, the protagonist of the TV show The Queen’s Gambit, is not someone you’d want as a friend. She takes money from her childhood mentor—the old janitor who taught her chess—and never pays him back, visits him or thanks him for launching her career. She treats the young men who help her improve—a group that eventually coalesces into a supportive entourage—in a similarly instrumental way. She is so focused on winning tournaments that she can barely spare a word of caution when her adoptive mother is falling into a fatal alcoholic spiral. When she loses, she is petulant and childish, unlike her opponents, who are graceful and kind. She is cruel and manipulative when—as an adult—she plays against a talented Russian child, softening to him only after she has beaten him.

Beth doesn’t seem to love anyone, but viewers love her anyways, admiring the sheer force of her genius. It doesn’t matter that most viewers don’t play chess. The chess scenes focus our attention on her striking, wide-set eyes, her perfect figure and her manicured fingernails, as though gawking at her body were a symbolic way of appreciating some mysterious power in her brain. We are clued in to her genius by other people saying she is “astonishing,” and by their willingness to put themselves at her service.

In my own field there are also geniuses.

More here.

The Gaia hypothesis states that our biosphere is evolving. Once sceptical, some prominent biologists are beginning to agree

W Ford Doolittle in Aeon:

The idea that the Earth itself is like a single evolving ‘organism’ was developed in the mid-1970s by the independent English scientist and inventor James Lovelock and the American biologist Lynn Margulis. They dubbed it the ‘Gaia hypothesis’, asserting that the biosphere is an ‘active adaptive control system able to maintain the Earth in homeostasis’. Sometimes they went pretty far with this line of reasoning: Lovelock even ventured that algal mats have evolved so as to control global temperature, while Australia’s Great Barrier Reef might be a ‘partly finished project for an evaporation lagoon’, whose purpose was to control oceanic salinity.

The idea that the Earth itself is like a single evolving ‘organism’ was developed in the mid-1970s by the independent English scientist and inventor James Lovelock and the American biologist Lynn Margulis. They dubbed it the ‘Gaia hypothesis’, asserting that the biosphere is an ‘active adaptive control system able to maintain the Earth in homeostasis’. Sometimes they went pretty far with this line of reasoning: Lovelock even ventured that algal mats have evolved so as to control global temperature, while Australia’s Great Barrier Reef might be a ‘partly finished project for an evaporation lagoon’, whose purpose was to control oceanic salinity.

The notion that the Earth itself is a living system captured the imagination of New Age enthusiasts, who deified Gaia as the Earth Goddess. But it has received rough treatment at the hands of evolutionary biologists like me, and is generally scorned by most scientific Darwinists. Most of them are still negative about Gaia: viewing many Earthly features as biological products might well have been extraordinarily fruitful, generating much good science, but Earth is nothing like an evolved organism. Algal mats and coral reefs are just not ‘adaptations’ that enhance Earth’s ‘fitness’ in the same way that eyes and wings contribute to the fitness of birds. Darwinian natural selection doesn’t work that way.

I’ve got a confession though: I’ve warmed to Gaia over the years.

More here.

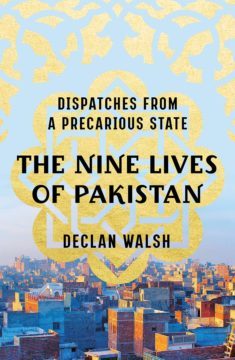

Pakistan Has Its Problems, but It Won’t Perish

Taimur Khan in Foreign Policy:

A decade before the arrival of New York Times correspondent Declan Walsh’s The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches from a Precarious State—which was released in the United States on Nov. 23—another major book of long-form reportage about the country’s chaotic post-9/11 years was published: Nicholas Schmidle’s To Live or to Perish Forever. The two books open with anecdotes of the authors being suddenly ordered to pack their bags and expelled from the country after reporting stories that crossed a red line for Pakistan’s security services—Schmidle for reporting on the Pakistani mutation of the Taliban and Walsh for his coverage of the insurgency in the vast, rural Balochistan province. Walsh’s book comes more than seven years after he was kicked out of Pakistan in May 2013.

A decade before the arrival of New York Times correspondent Declan Walsh’s The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches from a Precarious State—which was released in the United States on Nov. 23—another major book of long-form reportage about the country’s chaotic post-9/11 years was published: Nicholas Schmidle’s To Live or to Perish Forever. The two books open with anecdotes of the authors being suddenly ordered to pack their bags and expelled from the country after reporting stories that crossed a red line for Pakistan’s security services—Schmidle for reporting on the Pakistani mutation of the Taliban and Walsh for his coverage of the insurgency in the vast, rural Balochistan province. Walsh’s book comes more than seven years after he was kicked out of Pakistan in May 2013.

In news reporting, most of the work must frustratingly remain in a journalist’s notebook. Walsh draws on these notebooks to write his book, finally able to give previous reporting trips the full literary treatment that they deserve. But it raises the question of whether reporting from Pakistan, some of it nearly 20 years old, gives readers new insights into a uniquely complex society. Walsh himself claims he will take the reader with him, retracing his steps, on a journey “deep into the psyche of the country.”

Walsh’s book is better than Schmidle’s, but the nearly identical opening scenes are a metaphor for a larger problem with writing about Pakistan, an ethnically diverse nation of more than 200 million people that is in constant flux. In the decade between the publication of these two major books of reportage that purport to explain Pakistan, the country itself has grown and evolved rapidly. The Pakistan discourse has still not caught up.

More here.

The Mankiewicz Brothers’ Biographer Weighs in on David Fincher’s “Mank”

Sydney Ladensohn Stern in Literary Hub:

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

I spent the last decade researching and writing a dual biography of Herman and his younger, more successful brother, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, writer/director of, among others, the classic All About Eve and the notorious Cleopatra. Before he became a screenwriter, Herman was a New York newspaperman, a celebrated wit and Algonquin group habitué, a theatre critic for the New York Times and New Yorker, and a playwright collaborating with George S. Kaufman. Unfortunately, Herman was also an alcoholic and chronic gambler. He originally went to Hollywood in 1925 for a short writing assignment, intending to work there just long enough to pay off a gambling debt. Instead, he stayed for the rest of his life, despising the movie business but never managing to leave it. He drank himself to death in 1953 at the age of 55.

More here.

The search for the secular Jesus

Nick Spencer in Prospect Magazine:

Two hundred years ago, Thomas Jefferson, aged nearly 80 and living in comfortable retirement at Monticello, took a scalpel to his Bible. Jefferson had endured a bruising presidential campaign in 1800 in which it was alleged he was an atheist who would turn America into a “nation of atheists.” The choice, electors were told, was between “God and a religious president, or Jefferson and no god.” Under Jefferson, one preacher warned, “murder, robbery, rape… will be openly taught and practised [and] the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed.” American politics was dirty back then.

Jefferson won the election, and the next, but never shook off his reputation for godlessness. His biblical carve-up was not, however, an act of sacrilege or retribution for decades of smearing by the devout. Arguably, it was an undertaking of genuine and painstaking respect. His plan was to excise all references to incarnation, miracles and resurrection from the gospels. These were, he believed, nothing but the residue of a primitive and superstitious culture. In their place he would preserve only Jesus’s ethical teachings, “a system,” wrote Jefferson, “of the most sublime morality which has ever fallen from the lips of man.”

During the summer of 1820, he produced a slim document, about 84 pages, comprising around a thousand verses, which, as he saw it, rescued Jesus’s ethical gold from its supernatural dross. He eventually consented to have an outline printed without his name attached. The full document, which he called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth but came to be known as the Jefferson Bible, only came to light in the 1890s. It is the subject of Peter Manseau’s fine “biography,” the latest in Princeton University Press’s excellent series on the Lives of Great Religious Books.

The search for the purely “ethical Jesus” is probably as old as Christianity itself.

More here.

“Mank,” Reviewed: David Fincher’s Impassioned Dive Into Hollywood Politics

Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

The best thing about David Fincher’s new film, “Mank,” is that it isn’t about what one expects it to be about. More specifically, the movie (which is streaming on Netflix) is not about the assertion, made most strenuously by Pauline Kael in her controversial New Yorker piece “Raising Kane,” that Herman J. Mankiewicz, the veteran screenwriter, wrote the screenplay for “Citizen Kane” by himself and nearly had credit stolen from him by Orson Welles, the movie’s director, producer, star, and credited co-writer. Yes, that saga (which I revisited recently) is included in the film, but it is downplayed to the point of insignificance and near incomprehensibility. Rather, “Mank” is about why Mankiewicz wrote “Citizen Kane”—what experiences inspired him to write it and were essential to it, and why he was the only person who could have done so.

The best thing about David Fincher’s new film, “Mank,” is that it isn’t about what one expects it to be about. More specifically, the movie (which is streaming on Netflix) is not about the assertion, made most strenuously by Pauline Kael in her controversial New Yorker piece “Raising Kane,” that Herman J. Mankiewicz, the veteran screenwriter, wrote the screenplay for “Citizen Kane” by himself and nearly had credit stolen from him by Orson Welles, the movie’s director, producer, star, and credited co-writer. Yes, that saga (which I revisited recently) is included in the film, but it is downplayed to the point of insignificance and near incomprehensibility. Rather, “Mank” is about why Mankiewicz wrote “Citizen Kane”—what experiences inspired him to write it and were essential to it, and why he was the only person who could have done so.

The movie is not a “gotcha” movie, not a parroting of Kael’s argument, but, rather, an astutely probing and pain-filled work of speculative historical psychology—and a vision of Hollywood politics that shines a fervent plus ça change spotlight on current events. It is a film that left me with a peculiar impression—especially when I viewed it a second time, after brushing up on Mankiewicz’s story—that it is, in some ways, an inert cinematic object, lacking a dramatic spark. But its subject is fascinating, and its view of classic Hollywood is so personal, and passionately conflicted, that what takes place onscreen feels secondary to what it reveals of Fincher’s own directorial psychology—of his view of the business and the art of movies, and of his place in both.

Like “Citizen Kane,” “Mank” is a movie built with flashbacks.

More here.

Alison Lurie (1926 – 2020)

Miguel Algarín (1941 – 2020)

Rafer Johnson (1934 – 2020)

Sunday Poem

Think of Those Great Watchers

Think of those great watchers of the sky,

shepherds, magi, how they looked for

a thousand years and saw there was order,

who learned not only Light would return,

but the moment she’d start her journey.

No writing then. The see-ers gave

what they knew to the song-makers –

dreamy sons, daughters who hummed

as they spun, the priestly keepers of story –

and the clever-handed heard, nodded,

and turned poems into New Grange,

Stonehenge, The Great Temple of Karnak.

Saturday, December 5, 2020

The diminishing returns of distinction-making

Nan Z. Da in n + 1:

IN HER MEMOIR Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life, the contemporary Chinese American writer Yiyun Li recounts something that Marianne Moore’s mother had done, which recalled something that Li’s own mother had done. The young Marianne Moore had become attached to a kitten that she named Buffy, short for Buffalo. One day, her mother drowned the creature, an act of cruelty that Moore inexplicably defends: “We tend to run wild in these matters of personal affection but there may have been some good in it too.” Li appends a version of this story from her own childhood:

IN HER MEMOIR Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life, the contemporary Chinese American writer Yiyun Li recounts something that Marianne Moore’s mother had done, which recalled something that Li’s own mother had done. The young Marianne Moore had become attached to a kitten that she named Buffy, short for Buffalo. One day, her mother drowned the creature, an act of cruelty that Moore inexplicably defends: “We tend to run wild in these matters of personal affection but there may have been some good in it too.” Li appends a version of this story from her own childhood:

The menacing logic by which Moore’s mother functioned is familiar. When my sister started working after college, she gave me a pair of hamsters as a present . I became fond of them, and soon after they disappeared. I gave them away, my mother said; look how obsessed you are with them. You can’t even show the same devotion to your parents.

Having something that you love snatched away because you love it is maddening because there’s no way to gainsay it. You can only protest on the grounds that indeed you experience the attachment of which you’re accused. This leaves the child Li in a position roughly analogous to anyone who, having been punctured, bristles at the accusation of being thin-skinned. Protesting would have been to play into her mother’s hands, proving her mother right.

More here.

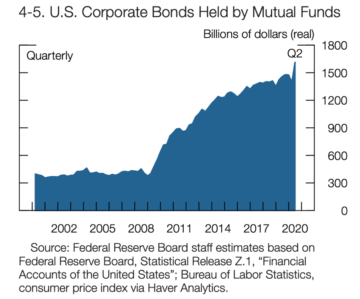

Financial Stability Three Ways

Over at his Chartbook newsletter, Adam Tooze explores how stable is the financial system?

Over at his Chartbook newsletter, Adam Tooze explores how stable is the financial system?

At least twice a year, the world’s central banks and international financial institutions like the IMF and the Financial Stability Board set themselves to answering this question. A typical rhythm is to publish two reports a year, one in the spring and one in the autumn. National central banks cover their respective territories. The IMF and the Financial Stability Report take a global view. In the last few weeks, we have had the reports from the IMF, the Fed and the ECB. The Bank of England does a very interesting report. So too does the Bank of Japan.

These are rich documents, stuffed with data, charts and commentary, a treasure trove for us to plunder for months on end. For today’s newsletter I thought it would be interesting to compare the reports issued by the Fed, the ECB and the IMF as documenting different points of view at this dramatic moment in the development of the world economy.

The Fed’s report breathes the air of 2008 and Dodd-Frank. It is an elegant, stripped down document that focuses on the essentials of financial stability i.e. credit risks arising from loans made to businesses and households and funding risks arising from the sources of funding used by banks, investment funds and insurers. The commentary is sparse. The Fed presumably does not want to give too much away. Nor does it want to find itself in hot political water.

More here.