Michael Prodger in New Statesman:

On February 1818, Samuel Taylor Cole-ridge was sent a copy of Songs of Innocence, William Blake’s first illustrated book of poems, which had been published some 30 years earlier. He was both impressed and discomfited by what he read. “You may smile at my calling another Poet a Mystic,” Coleridge, by then a fully fledged opium addict, wrote to a friend, “but verily I am in the very mire of commonplace common sense compared with Mr Blake.” Coleridge was not, of course, the first or last person to be mired.

On February 1818, Samuel Taylor Cole-ridge was sent a copy of Songs of Innocence, William Blake’s first illustrated book of poems, which had been published some 30 years earlier. He was both impressed and discomfited by what he read. “You may smile at my calling another Poet a Mystic,” Coleridge, by then a fully fledged opium addict, wrote to a friend, “but verily I am in the very mire of commonplace common sense compared with Mr Blake.” Coleridge was not, of course, the first or last person to be mired.

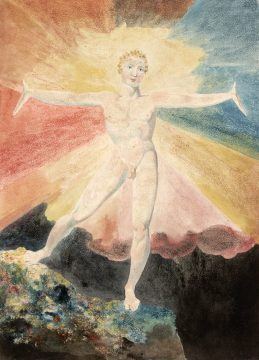

Blake’s offbeat character – from his naturism and convoluted, self-invented cosmology to his visions of angels sitting in trees and his political and religious nonconformism – forms a carapace so tough as to be nigh-on impenetrable. The fact that his quirks were not so much elements of the man but the man himself means that he can be too daunting to comprehend properly. He once said of his illustrated poems that “My style of designing is a species by itself” and Blake too can perhaps be best characterised as a species in himself.

Whatever Blake was – poet, prophet and sage, or “Rebel, Radical, Revolutionary” as the poster to Tate Britain’s extraordinary new survey of his career somewhat sensationally puts it – he was primarily, and from first to last, a professional artist. For much of his life he spent his days as a highly regarded freelance commercial engraver; his evenings he gave over to his watercolours and relief etchings – intended as saleable products; and it was only late at night that he became a poet, composing in snatches when he had a few moments to spare.

More here.