Jeff Sharlet in Bookforum:

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

I STARTED WRITING THIS ESSAY on the hate under which we all now live the night of Trump’s first debate with Joe Biden. I was trying to think through two new books, Seyward Darby’s Sisters in Hate and Jean Guerrero’s Hatemonger, both smartly reported and urgent. But I stalled. I could read the books, but I didn’t know if I had it in me to write about them. I’d learned, like so many of us, to look away.

I hadn’t given up the hate beat entirely since my heart attack. I’d grown careful.

Last fall, when I started reporting on Trump rallies again, instead of drinking my fear into submission afterward, I’d go for long walks. I read these books while walking the dirt roads where I live now, roads so quiet I could walk and read. But often I’d pause, neither reading nor walking. I considered the question of how to write about hate, what these books—Darby’s, on the internal lives of female leaders of what remains (for now) fringe white nationalism, and Guerrero’s, about Trump senior adviser and speechwriter Stephen Miller, who is mainstreaming those beliefs—might say about the taxonomy of hate, the methodology of its study. As if looking at hate was a matter of professional curiosity.

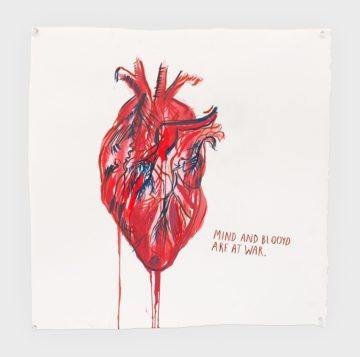

I had thoughts! But I couldn’t keep what I’d read in my mind, my gut, my—maybe you’ll forgive the cliché—my heart. I’d reached saturation. Or maybe I was finally getting it, the “joke,” which is that you don’t need to go looking for hate. It’s always right there, mundane. I remembered a 2017 New York Times profile of a suburban neo-Nazi, how many accused it of “normalizing” its subject. I hadn’t thought much of it—no need to play neutral with fascism—but I hadn’t agreed when people said it didn’t matter if the Nazi liked Seinfeld and Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim. I thought there was no “normalizing” him, because he was all too normal. It seemed critical to understand the ways in which the antifascist del Toro’s art could be repurposed as hate. If it could happen to del Toro it could happen to anybody. We are, none of us, especially given the whiteness—the anti-Blackness—coded within us all by white supremacy, as far from the Nazi as we want to be. My problem with the Nazi next door wasn’t that we knew too much about him. We didn’t know enough.

More here.

Spider legs seem to have minds of their own. According to findings published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, each leg functions as a semi-independent “computer,” with sensors that read the immediate environment and trigger movements accordingly. This autonomy helps the arachnids quickly spin perfect webs with minimal brain use. The study authors simulated surprisingly simple rules to govern this complex behavior—which could eventually be applied to robotics.

Spider legs seem to have minds of their own. According to findings published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, each leg functions as a semi-independent “computer,” with sensors that read the immediate environment and trigger movements accordingly. This autonomy helps the arachnids quickly spin perfect webs with minimal brain use. The study authors simulated surprisingly simple rules to govern this complex behavior—which could eventually be applied to robotics.

Critics of Silicon Valley censorship for years heard the same refrain: tech platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter are private corporations and can host or ban whoever they want. If you don’t like what they are doing, the solution is not to complain or to regulate them. Instead, go create your own social media platform that operates the way you think it should.

Critics of Silicon Valley censorship for years heard the same refrain: tech platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter are private corporations and can host or ban whoever they want. If you don’t like what they are doing, the solution is not to complain or to regulate them. Instead, go create your own social media platform that operates the way you think it should.

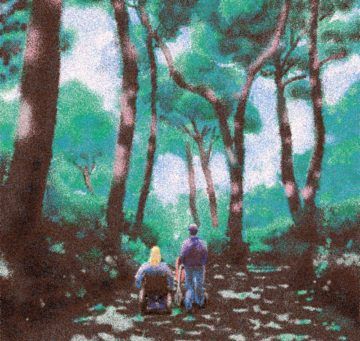

It was a night in mid-April that I fell asleep to the phrase this is too hard pinging through my brain, and they were the first words to cross my mind when I opened my eyes the next morning. I texted my sisters: “Remember the easy days when it was JUST a baby and cancer???” I pulled myself out of bed, plopped heavily into my wheelchair and stared in the mirror with my fingers splayed across my growing belly. That day we had to decide if my partner Micah would start a second round of chemotherapy treatments that would weaken his ability to fight against this new virus if he caught it, or forgo the treatment and change his odds against cancer. Our baby would arrive in a few weeks.

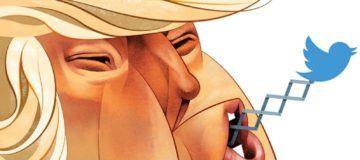

It was a night in mid-April that I fell asleep to the phrase this is too hard pinging through my brain, and they were the first words to cross my mind when I opened my eyes the next morning. I texted my sisters: “Remember the easy days when it was JUST a baby and cancer???” I pulled myself out of bed, plopped heavily into my wheelchair and stared in the mirror with my fingers splayed across my growing belly. That day we had to decide if my partner Micah would start a second round of chemotherapy treatments that would weaken his ability to fight against this new virus if he caught it, or forgo the treatment and change his odds against cancer. Our baby would arrive in a few weeks. After Donald Trump lost the US presidency last year, he retained the consolation prize of his Twitter account. Commentators debated how Mr Trump would seek to profit from the 88 million followers he had accumulated: a new TV career or another presidential bid? Yet on 8 January, he lost his cherished platform after he was permanently suspended by Twitter because of “the risk of further incitement of violence”. Two days earlier a rabble of Trump fanatics, conspiracy theorists and white supremacists had stormed the US Capitol, resulting in five deaths. In a video posted on Twitter, Mr Trump told the mob, “We love you” and later tweeted: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide victory is so viciously & unceremoniously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long.”

After Donald Trump lost the US presidency last year, he retained the consolation prize of his Twitter account. Commentators debated how Mr Trump would seek to profit from the 88 million followers he had accumulated: a new TV career or another presidential bid? Yet on 8 January, he lost his cherished platform after he was permanently suspended by Twitter because of “the risk of further incitement of violence”. Two days earlier a rabble of Trump fanatics, conspiracy theorists and white supremacists had stormed the US Capitol, resulting in five deaths. In a video posted on Twitter, Mr Trump told the mob, “We love you” and later tweeted: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide victory is so viciously & unceremoniously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long.” So much has been written on the Heide group of artists, Nolan, Tucker, Hester, and their patrons John and Sunday Reed that it is hard to imagine anything more could be added. π.ο.’s Heide however, though holding this group of communalism, camaraderie, and free love as its centre, radiates backwards to the history that precedes the Reeds’ utopian endeavour, and continues into its aftermath. One epigraph from Oscar Wilde signals Heide’s intent: ‘The only duty we have to history is to rewrite it.’ Artists tumble out in artistic lineage from Buvelot to the Heidelberg School to Heide, along with numerous glancing biographies of influential patrons and politicians, William Barak, Ned Kelly, Albert Namatjira, Patrick White, Billy Hyde, Eliza Fraser, and many others. Through these intersecting histories, Heide also depicts the struggle between the conservation of the past and revolt against it, as epitomised in the Ern Malley hoax, with Angry Penguins magazine briefly funded by the Reeds, and the recurring compromises that swing between capital and art; ‘Only an Artist, can break out of / a straight-jacket.’. But it is his poetic technique that most energetically enacts these struggles, forging a dense amalgam in which past and present continually invade each other. Where π.ο.’s earlier Fitzroy: The Biography catalogued portraits of famous, notorious, and lesser known characters, Heide commences with ‘Terra Australis’ that cryptically lampoons its title, then to Cook’s voyage, and gradually progresses to the establishment of the State Library and the National Gallery of Victoria in 1850s colonial Melbourne, and eventually to the artists hammering to enter or exit those institutions. Escapee William Buckley and explorers Leichhardt and Burke and Wills are also among these seekers of the new: ‘On the horizon: / 23 horses, 19 men, and 26 camels on / a slow walk across / a blank slate.’ This imaginary ‘blank slate’ is equivalent to the unpolished metropolis without its establishments of arts and learning, and these doomed or heralded figures parallel the relentless pursuit of art.

So much has been written on the Heide group of artists, Nolan, Tucker, Hester, and their patrons John and Sunday Reed that it is hard to imagine anything more could be added. π.ο.’s Heide however, though holding this group of communalism, camaraderie, and free love as its centre, radiates backwards to the history that precedes the Reeds’ utopian endeavour, and continues into its aftermath. One epigraph from Oscar Wilde signals Heide’s intent: ‘The only duty we have to history is to rewrite it.’ Artists tumble out in artistic lineage from Buvelot to the Heidelberg School to Heide, along with numerous glancing biographies of influential patrons and politicians, William Barak, Ned Kelly, Albert Namatjira, Patrick White, Billy Hyde, Eliza Fraser, and many others. Through these intersecting histories, Heide also depicts the struggle between the conservation of the past and revolt against it, as epitomised in the Ern Malley hoax, with Angry Penguins magazine briefly funded by the Reeds, and the recurring compromises that swing between capital and art; ‘Only an Artist, can break out of / a straight-jacket.’. But it is his poetic technique that most energetically enacts these struggles, forging a dense amalgam in which past and present continually invade each other. Where π.ο.’s earlier Fitzroy: The Biography catalogued portraits of famous, notorious, and lesser known characters, Heide commences with ‘Terra Australis’ that cryptically lampoons its title, then to Cook’s voyage, and gradually progresses to the establishment of the State Library and the National Gallery of Victoria in 1850s colonial Melbourne, and eventually to the artists hammering to enter or exit those institutions. Escapee William Buckley and explorers Leichhardt and Burke and Wills are also among these seekers of the new: ‘On the horizon: / 23 horses, 19 men, and 26 camels on / a slow walk across / a blank slate.’ This imaginary ‘blank slate’ is equivalent to the unpolished metropolis without its establishments of arts and learning, and these doomed or heralded figures parallel the relentless pursuit of art. The plaques and firsts are the least interesting part of her story, though. Above all, Butler was an observer and ponderer. The probing mind that animates her novels, short stories and essays is obsessed with the viability of the human enterprise. Will we survive our worst habits? Will we change? Do we want to?

The plaques and firsts are the least interesting part of her story, though. Above all, Butler was an observer and ponderer. The probing mind that animates her novels, short stories and essays is obsessed with the viability of the human enterprise. Will we survive our worst habits? Will we change? Do we want to? Yakov Feygin in Phenomenal World:

Yakov Feygin in Phenomenal World: Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite interviews Katrina Forrester over at Renewal:

Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite interviews Katrina Forrester over at Renewal: Houman Barekat in LA Review of Books:

Houman Barekat in LA Review of Books: Mike Konczal in Boston Review:

Mike Konczal in Boston Review: Like school, work conferences and visiting your grandparents, this year’s

Like school, work conferences and visiting your grandparents, this year’s  Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

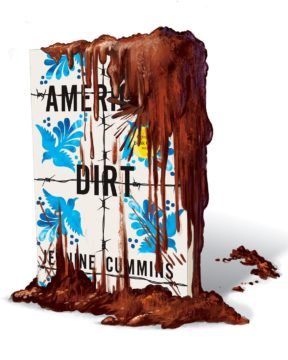

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability. On a mild Monday this past February, a tense meeting unfolded in a skyscraper in downtown Manhattan. Four Latinx writers and activists sat on one side of a long conference table. Facing them was a collection of white editors and executives from Macmillan, the publishing house that had recently put out

On a mild Monday this past February, a tense meeting unfolded in a skyscraper in downtown Manhattan. Four Latinx writers and activists sat on one side of a long conference table. Facing them was a collection of white editors and executives from Macmillan, the publishing house that had recently put out