Emine Saner in The Guardian:

It was 10 years ago that Kate Mosse got the idea for her latest series of historical novels – and immediately tried to talk herself out of it. “I just thought: ‘Don’t do this, Kate – you know nothing about the French wars of religion, nothing about the 17th and 18th centuries. This whole history is obviously a minefield,” she recalls. Despite those initial reservations, she eventually embarked on what would become a quartet of novels about the French Protestants known as the Huguenots, beginning in 16th-century Languedoc with The Burning Chambers (published in 2018) and following the diaspora across two continents and three centuries. It’s not as if she had much else on – only a few other books, a couple of plays, keeping the Women’s prize for fiction going, railing against Brexit and being a carer.

It was 10 years ago that Kate Mosse got the idea for her latest series of historical novels – and immediately tried to talk herself out of it. “I just thought: ‘Don’t do this, Kate – you know nothing about the French wars of religion, nothing about the 17th and 18th centuries. This whole history is obviously a minefield,” she recalls. Despite those initial reservations, she eventually embarked on what would become a quartet of novels about the French Protestants known as the Huguenots, beginning in 16th-century Languedoc with The Burning Chambers (published in 2018) and following the diaspora across two continents and three centuries. It’s not as if she had much else on – only a few other books, a couple of plays, keeping the Women’s prize for fiction going, railing against Brexit and being a carer.

Even during the pandemic, she has been incredibly productive – the initial shock of it “felt like grief” she says, and she couldn’t concentrate on writing, so instead she read more than 250 golden age detective books. The City of Tears, the sequel to The Burning Chambers, should have been released in May last year and she would have spent much of 2020 promoting it; instead, she is now working on the third instalment of the series. And then she wrote another book, out later this year, about her role as a carer – first helping her mother look after her father, who had Parkinson’s and died in 2011, and now for her 90-year-old mother-in-law, Rosie. In order to protect Rosie, who lives with Mosse and her husband, Greg, the household has been virtually self-isolating since March.

Mosse’s move into historical fiction changed her life with the success of Labyrinth – a Holy Grail adventure story – in 2005, and the following two books in her Languedoc trilogy, so this return to the genre has felt exciting, she says. When her father was diagnosed, Mosse decided not to work on any research-heavy books that required long periods of travel, in order to support her parents – they also both lived with Mosse and her husband. “Sadly, my dad died in 2011 and then my ma died in 2014,” she says. “Then for a period of time, I could be back out, doing research, and it’s been a really lovely thing to have this huge project.”

More here.

Like his many previous literary endeavors, Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk’s new book Orange is about Istanbul, or rather how the city appears in his eyes. The book consists of color photographs of the city’s streets which Pamuk has been perpetually constantly taking for several years, always with the same technique and choice of motif. The result is a visual essay dedicated to the alleys and corners of his hometown. Over the author’s more than six decades living in Istanbul, Pamuk has witnessed the constant transformation of the city, notably from the gradual change from orange street lamps to white over the last ten years or so, not that the actual duration of the change matters. What does matter is the stark visible disappearance of the yellow-hued fluorescent lamps bringing a loss of the magical moments in a city landscape he dearly loves; the change is one he accepts only with some bitterness.

Like his many previous literary endeavors, Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk’s new book Orange is about Istanbul, or rather how the city appears in his eyes. The book consists of color photographs of the city’s streets which Pamuk has been perpetually constantly taking for several years, always with the same technique and choice of motif. The result is a visual essay dedicated to the alleys and corners of his hometown. Over the author’s more than six decades living in Istanbul, Pamuk has witnessed the constant transformation of the city, notably from the gradual change from orange street lamps to white over the last ten years or so, not that the actual duration of the change matters. What does matter is the stark visible disappearance of the yellow-hued fluorescent lamps bringing a loss of the magical moments in a city landscape he dearly loves; the change is one he accepts only with some bitterness.

The daily press conferences from Downing Street since March 2020 underline the prominence given to epidemiologists, behavioural scientists and the medical profession in driving policy reaction to the Covid-19 crisis. This may be evidence of a welcome return of scientific expertise to the heart of government after a period when much of the population and elements of the government had, in the words of

The daily press conferences from Downing Street since March 2020 underline the prominence given to epidemiologists, behavioural scientists and the medical profession in driving policy reaction to the Covid-19 crisis. This may be evidence of a welcome return of scientific expertise to the heart of government after a period when much of the population and elements of the government had, in the words of  We still don’t have all the technologies we need to address climate change.

We still don’t have all the technologies we need to address climate change. L

L Hester Street contains no muckraking impulse to uncover the “truth” of How the Other Half Lives. She rejected any sort of outsider gaze in favor of an awareness to the cadences of Yiddish, the shimmering falling leaves as an immigrant son and his father learn how to play baseball in a sun-kissed park, the loving camera effect gotten out of Keats’s blindingly over-exposed white shirt. It’s a perceptiveness that doesn’t advertise how perceptive it is. Much of Hester Street is consumed with the ordinary problem of how Carol Kane should style her wild hair, what raiment she should cross Delancey Street in, which hat to wear. Nearly a century after the events of Hester Street, in Crossing Delancey (my favorite Silver film, a rom-com set in contemporary 1988 New York), Amy Irving is obsessed by the same problem: whether to wear a Diane Keaton-ish bowler hat that was gifted to her by the owner of a pickle shop (Peter Riegert). The past constantly revives in Silver; newer generations never forget where they came from; time ebbs and flows in and out of style.

Hester Street contains no muckraking impulse to uncover the “truth” of How the Other Half Lives. She rejected any sort of outsider gaze in favor of an awareness to the cadences of Yiddish, the shimmering falling leaves as an immigrant son and his father learn how to play baseball in a sun-kissed park, the loving camera effect gotten out of Keats’s blindingly over-exposed white shirt. It’s a perceptiveness that doesn’t advertise how perceptive it is. Much of Hester Street is consumed with the ordinary problem of how Carol Kane should style her wild hair, what raiment she should cross Delancey Street in, which hat to wear. Nearly a century after the events of Hester Street, in Crossing Delancey (my favorite Silver film, a rom-com set in contemporary 1988 New York), Amy Irving is obsessed by the same problem: whether to wear a Diane Keaton-ish bowler hat that was gifted to her by the owner of a pickle shop (Peter Riegert). The past constantly revives in Silver; newer generations never forget where they came from; time ebbs and flows in and out of style. It could be considered a small thing that Trump can neither meet with Biden nor acknowledge that he has lost the election to him. But what if the refusal to acknowledge loss is bound up with the path of destruction we call Trump’s exit route? Why is it so hard to lose? The question has at least two meanings in these times. So many of us are losing people to Covid-19, or fearing death for ourselves or others. All of us are living in relation to ambient illness and death, whether or not we have a name for that sense of the atmosphere. Death and illness are quite literally in the air. And yet, it is unclear how to name or fathom these losses, and the resistance of Trump to public mourning has drawn from, and intensified, a masculinist refusal to mourn that is bound up with nationalist pride and even white supremacy. The Trumpists tend not to grieve openly pandemic deaths. They have conventionally rejected the numbers as exaggerated (“fake news!”) or defied the threat of death with their gatherings and maskless marauding through the public spaces, most recently in their spectacle of thuggery in the US Capitol in animal costumes. Trump never acknowledged the losses the US has suffered, and had no inclination or capacity to offer condolences. When the losses were referenced, they were not so bad, the curve was flattening, the pandemic would be short, it was not his fault, it was China’s fault. What people need, he claimed, was to get back to work because they were “dying” at home, by which he meant only that they were driven crazy by domestic confinement.

It could be considered a small thing that Trump can neither meet with Biden nor acknowledge that he has lost the election to him. But what if the refusal to acknowledge loss is bound up with the path of destruction we call Trump’s exit route? Why is it so hard to lose? The question has at least two meanings in these times. So many of us are losing people to Covid-19, or fearing death for ourselves or others. All of us are living in relation to ambient illness and death, whether or not we have a name for that sense of the atmosphere. Death and illness are quite literally in the air. And yet, it is unclear how to name or fathom these losses, and the resistance of Trump to public mourning has drawn from, and intensified, a masculinist refusal to mourn that is bound up with nationalist pride and even white supremacy. The Trumpists tend not to grieve openly pandemic deaths. They have conventionally rejected the numbers as exaggerated (“fake news!”) or defied the threat of death with their gatherings and maskless marauding through the public spaces, most recently in their spectacle of thuggery in the US Capitol in animal costumes. Trump never acknowledged the losses the US has suffered, and had no inclination or capacity to offer condolences. When the losses were referenced, they were not so bad, the curve was flattening, the pandemic would be short, it was not his fault, it was China’s fault. What people need, he claimed, was to get back to work because they were “dying” at home, by which he meant only that they were driven crazy by domestic confinement. Precisely at noon on Wednesday,

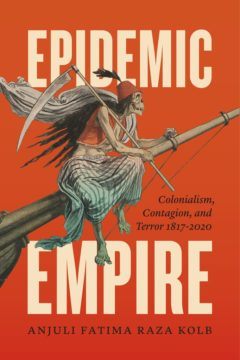

Precisely at noon on Wednesday,  Anne Schult: Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, reflections on contagious disease as allegory have abounded, and some of the most canonical texts engaging with this trope—from Susan Sontag’s

Anne Schult: Over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, reflections on contagious disease as allegory have abounded, and some of the most canonical texts engaging with this trope—from Susan Sontag’s  What is the world made of? How does it behave? These questions, aimed at the most basic level of reality, are the subject of fundamental physics. What counts as fundamental is somewhat contestable, but it includes our best understanding of matter and energy, space and time, and dynamical laws, as well as complex emergent structures and the sweep of the cosmos. Few people are better positioned to talk about fundamental physics than Frank Wilczek, a Nobel Laureate who has made significant contributions to our understanding of the strong interactions, dark matter, black holes, and condensed matter, as well as proposing the existence of

What is the world made of? How does it behave? These questions, aimed at the most basic level of reality, are the subject of fundamental physics. What counts as fundamental is somewhat contestable, but it includes our best understanding of matter and energy, space and time, and dynamical laws, as well as complex emergent structures and the sweep of the cosmos. Few people are better positioned to talk about fundamental physics than Frank Wilczek, a Nobel Laureate who has made significant contributions to our understanding of the strong interactions, dark matter, black holes, and condensed matter, as well as proposing the existence of  It is time to define responsibility and hold these companies accountable for how they aid and abet criminal activity. And it is time to listen to those who have shouted from the rooftops about these issues for years, as opposed to allowing Silicon Valley leaders to dictate the terms.

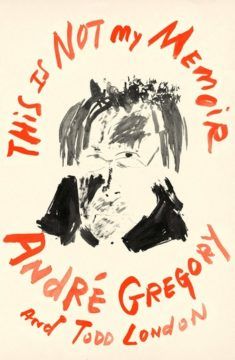

It is time to define responsibility and hold these companies accountable for how they aid and abet criminal activity. And it is time to listen to those who have shouted from the rooftops about these issues for years, as opposed to allowing Silicon Valley leaders to dictate the terms. Earlier in his career, Gregory writes, theater was a “drug to relieve the pain of living.” But escaping into his “calling” came with no shortage of throbbing side effects. One of the “most awful” days of Gregory’s life is the one when he directs a scene at Strasberg’s Actors Studio only to receive a brutal critique from the famed teacher in front of his fellow students, among them Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman. (He’d stay away from Strasberg’s class for months.) The belated success of his Alice came only after a succession of early failures: being fired from three consecutive directorships at small regional theaters. An “enfant terrible” in these years, Gregory hired a chemist to synthesize the smell of “rotting flesh” for a production in Philadelphia, resulting in an actor vomiting during a tech rehearsal and Gregory’s dismissal from the play. Another firing, from a theater in Los Angeles, came after he was punched by the program’s benefactor, the movie star Gregory Peck.

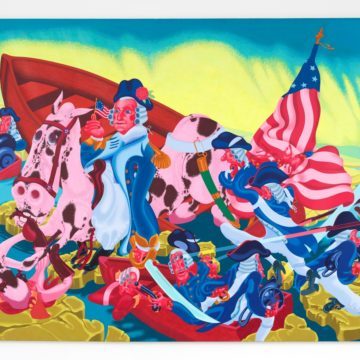

Earlier in his career, Gregory writes, theater was a “drug to relieve the pain of living.” But escaping into his “calling” came with no shortage of throbbing side effects. One of the “most awful” days of Gregory’s life is the one when he directs a scene at Strasberg’s Actors Studio only to receive a brutal critique from the famed teacher in front of his fellow students, among them Marilyn Monroe and Paul Newman. (He’d stay away from Strasberg’s class for months.) The belated success of his Alice came only after a succession of early failures: being fired from three consecutive directorships at small regional theaters. An “enfant terrible” in these years, Gregory hired a chemist to synthesize the smell of “rotting flesh” for a production in Philadelphia, resulting in an actor vomiting during a tech rehearsal and Gregory’s dismissal from the play. Another firing, from a theater in Los Angeles, came after he was punched by the program’s benefactor, the movie star Gregory Peck. A mild sensation in the late Sixties, a cult artist in the early Aughts, and now a seasoned art world veteran, Saul, who is 86, is having a moment. “How long until Peter Saul is rediscovered once and for all,” Beau Rutland wrote on the occasion of Saul’s comprehensive 2017 show at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. European retrospectives and newly respectful reviews have culminated in a two-floor survey at the New Museum last February. It is Saul’s first retrospective in New York City, accompanied by a lavish catalog and the publication of his “professional artist correspondence,” a fascinating collection of letters written to his parents and his longtime gallerist Allan Frumkin.

A mild sensation in the late Sixties, a cult artist in the early Aughts, and now a seasoned art world veteran, Saul, who is 86, is having a moment. “How long until Peter Saul is rediscovered once and for all,” Beau Rutland wrote on the occasion of Saul’s comprehensive 2017 show at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt. European retrospectives and newly respectful reviews have culminated in a two-floor survey at the New Museum last February. It is Saul’s first retrospective in New York City, accompanied by a lavish catalog and the publication of his “professional artist correspondence,” a fascinating collection of letters written to his parents and his longtime gallerist Allan Frumkin. It was 10 years ago that

It was 10 years ago that  After 35 years of sharing everything from a love for jazz music to tubes of lip gloss, twins Kimberly and Kelly Standard assumed that when they became sick with Covid-19 their experiences would be as identical as their DNA. The virus had different plans. Early last spring, the sisters from Rochester, Michigan, checked themselves into the hospital with fevers and shortness of breath. While Kelly was discharged after less than a week, her sister ended up in intensive care. Kimberly spent almost a month in critical condition, breathing through tubes and dipping in and out of shock. Weeks after Kelly had returned to their shared home, Kimberly was still relearning how to speak, walk and chew and swallow solid food she could barely taste. Nearly a year later, the sisters are bedeviled by the bizarrely divergent paths their illnesses took.

After 35 years of sharing everything from a love for jazz music to tubes of lip gloss, twins Kimberly and Kelly Standard assumed that when they became sick with Covid-19 their experiences would be as identical as their DNA. The virus had different plans. Early last spring, the sisters from Rochester, Michigan, checked themselves into the hospital with fevers and shortness of breath. While Kelly was discharged after less than a week, her sister ended up in intensive care. Kimberly spent almost a month in critical condition, breathing through tubes and dipping in and out of shock. Weeks after Kelly had returned to their shared home, Kimberly was still relearning how to speak, walk and chew and swallow solid food she could barely taste. Nearly a year later, the sisters are bedeviled by the bizarrely divergent paths their illnesses took. Over the past 10 years, numerous studies have shown that our obsession with happiness and high personal confidence may be making us less content with our lives, and less effective at reaching our actual goals. Indeed, we may often be happier when we stop focusing on happiness altogether.

Over the past 10 years, numerous studies have shown that our obsession with happiness and high personal confidence may be making us less content with our lives, and less effective at reaching our actual goals. Indeed, we may often be happier when we stop focusing on happiness altogether.