Emily Oster in The New York Times:

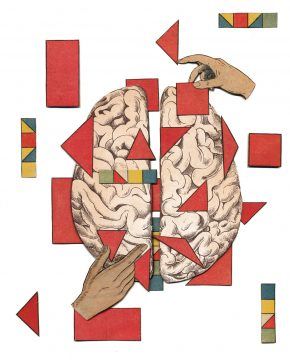

Piano players’ brains look different from those of violin players. Researchers have shown changes in brain activity in response to a short-term intervention in which girls played Tetris regularly — their visual-spatial brain areas seemed to enlarge. Such evidence of brain plasticity is key to Gina Rippon’s new book, “Gender and Our Brains” (which, yes, does relate the story of Phineas Gage, as well as that of the dead fish). The book is, at the core, concerned with the question of whether male and female brains are different. Rippon, a British professor of cognitive neuroimaging, reviews the history of studies of the gendered brain. The most persistent feature of these studies is the focus on size. Men have bigger brains on average, going along with their generally larger bodies, a fact that has come up again and again as an argument for male superiority, or at least structural difference. Size has fallen out of fashion, but the desire to identify gender-specific parts of the brain has not.

Piano players’ brains look different from those of violin players. Researchers have shown changes in brain activity in response to a short-term intervention in which girls played Tetris regularly — their visual-spatial brain areas seemed to enlarge. Such evidence of brain plasticity is key to Gina Rippon’s new book, “Gender and Our Brains” (which, yes, does relate the story of Phineas Gage, as well as that of the dead fish). The book is, at the core, concerned with the question of whether male and female brains are different. Rippon, a British professor of cognitive neuroimaging, reviews the history of studies of the gendered brain. The most persistent feature of these studies is the focus on size. Men have bigger brains on average, going along with their generally larger bodies, a fact that has come up again and again as an argument for male superiority, or at least structural difference. Size has fallen out of fashion, but the desire to identify gender-specific parts of the brain has not.

Rippon’s key thesis, however, is that once we recognize the existence of brain plasticity, this entire enterprise seems nonsensical. In her telling, girls and boys are treated differently from birth — even, possibly, from conception, as she relates the potential impact (far-fetched though it seems to me) of gender-reveal parties on fetal brain development. And this differential treatment will lead their brains to develop differently. If you put your boy baby in a truck onesie and your girl baby in a princess onesie, you’re already having an impact. Given this argument, virtually any evidence we might have about differences between male and female brains is suspect. The answer may well be yes, brains appear systematically different across genders — but you’ll never know if this reflects some underlying structural difference, or whether it’s simply the result of different treatment.

More here.