Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

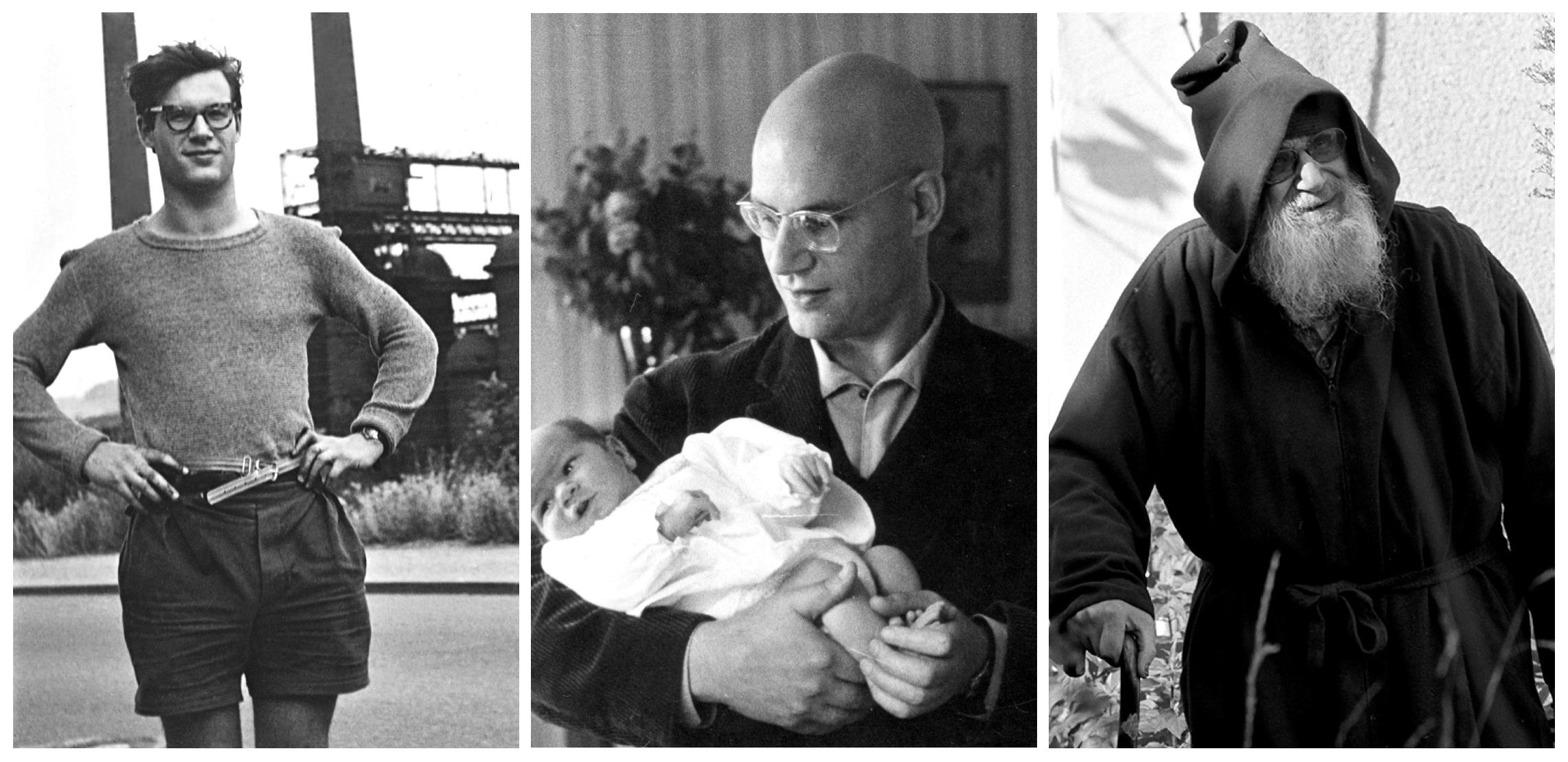

In 1947, Kurt Gödel, Albert Einstein, and Oskar Morgenstern drove from Princeton to Trenton in Morgenstern’s car. The three men, who’d fled Nazi Europe and become close friends at the Institute for Advanced Study, were on their way to a courthouse where Gödel, an Austrian exile, was scheduled to take the U.S.-citizenship exam, something his two friends had done already. Morgenstern had founded game theory, Einstein had founded the theory of relativity, and Gödel, the greatest logician since Aristotle, had revolutionized mathematics and philosophy with his incompleteness theorems. Morgenstern drove. Gödel sat in the back. Einstein, up front with Morgenstern, turned around and said, teasing, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Gödel looked stricken.

In 1947, Kurt Gödel, Albert Einstein, and Oskar Morgenstern drove from Princeton to Trenton in Morgenstern’s car. The three men, who’d fled Nazi Europe and become close friends at the Institute for Advanced Study, were on their way to a courthouse where Gödel, an Austrian exile, was scheduled to take the U.S.-citizenship exam, something his two friends had done already. Morgenstern had founded game theory, Einstein had founded the theory of relativity, and Gödel, the greatest logician since Aristotle, had revolutionized mathematics and philosophy with his incompleteness theorems. Morgenstern drove. Gödel sat in the back. Einstein, up front with Morgenstern, turned around and said, teasing, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Gödel looked stricken.

To prepare for his citizenship test, knowing that he’d be asked questions about the U.S. Constitution, Gödel had dedicated himself to the study of American history and constitutional law. Time and again, he’d phoned Morgenstern with rising panic about the exam. (Gödel, a paranoid recluse who later died of starvation, used the telephone to speak with people even when they were in the same room.) Morgenstern reassured him that “at most they might ask what sort of government we have.” But Gödel only grew more upset. Eventually, as Morgenstern later recalled, “he rather excitedly told me that in looking at the Constitution, to his distress, he had found some inner contradictions and that he could show how in a perfectly legal manner it would be possible for somebody to become a dictator and set up a Fascist regime, never intended by those who drew up the Constitution.” He’d found a logical flaw. Morgenstern told Einstein about Gödel’s theory; both of them told Gödel not to bring it up during the exam. When they got to the courtroom, the three men sat before a judge, who asked Gödel about the Austrian government.

“That is very bad,” the judge replied. “This could not happen in this country.”

Morgenstern and Einstein must have exchanged anxious glances. Gödel could not be stopped.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “I can prove it.”

“Oh, God, let’s not go into this,” the judge said, and ended the examination.

More here.

Natural selection seems, at first glance, to be so frustratingly inefficient. Generation after generation of baby gazelles are born, destined to be eaten by lions. Only by chance is one baby born with longer legs, able to run faster, and so escape being eaten. Of course, the very beauty of natural selection is that it doesn’t require any foresight; natural selection explains life in the universe precisely because there is no presumption of any prior knowledge. No Creator is necessary, because the evolutionary process is guaranteed to proceed even without any predefined rules. Life evolves—albeit slowly—without having to know where it’s going.

Natural selection seems, at first glance, to be so frustratingly inefficient. Generation after generation of baby gazelles are born, destined to be eaten by lions. Only by chance is one baby born with longer legs, able to run faster, and so escape being eaten. Of course, the very beauty of natural selection is that it doesn’t require any foresight; natural selection explains life in the universe precisely because there is no presumption of any prior knowledge. No Creator is necessary, because the evolutionary process is guaranteed to proceed even without any predefined rules. Life evolves—albeit slowly—without having to know where it’s going. An especially mysterious manifestation of the materiality of language in these poems is the projection of voice from, or into, the material world. Repeatedly, at special moments, things speak: “the hollyhocks spoke”; “Freezing rain with silver seems to be speaking”; “these colors speak”; “The sky speaks to me”; “The roofs speak”; “the room alive speaks when the corpse speaks… and the earth speaks”; “the trees and grass are speaking”; “the old sun / is speaking.” This eruption of voice from things—Gizzi calls it “thinging,” in a pun on “singing”—seems to mark that recovery of the world that Gizzi associates with elegy in the second “Now It’s Dark” poem. However, in the volume Now It’s Dark, that recovery is purchased at the price of another loss, that of “the speaking subject,” as it is called in psycholinguistic theory, or the one who says “I,” in the traditional view of lyric poetry. Drawing on that theory, Language writers accused lyric poetry of escaping into an illusory interior world inhabited by an equally illusory “I.”

An especially mysterious manifestation of the materiality of language in these poems is the projection of voice from, or into, the material world. Repeatedly, at special moments, things speak: “the hollyhocks spoke”; “Freezing rain with silver seems to be speaking”; “these colors speak”; “The sky speaks to me”; “The roofs speak”; “the room alive speaks when the corpse speaks… and the earth speaks”; “the trees and grass are speaking”; “the old sun / is speaking.” This eruption of voice from things—Gizzi calls it “thinging,” in a pun on “singing”—seems to mark that recovery of the world that Gizzi associates with elegy in the second “Now It’s Dark” poem. However, in the volume Now It’s Dark, that recovery is purchased at the price of another loss, that of “the speaking subject,” as it is called in psycholinguistic theory, or the one who says “I,” in the traditional view of lyric poetry. Drawing on that theory, Language writers accused lyric poetry of escaping into an illusory interior world inhabited by an equally illusory “I.” The world’s oldest known wooden sculpture — a nine-foot-tall totem pole thousands of years old — looms over a hushed chamber of an obscure Russian museum in the Ural Mountains, not far from the Siberian border. As mysterious as the huge stone figures of Easter Island, the Shigir Idol, as it is called, is a landscape of uneasy spirits that baffles the modern onlooker.

The world’s oldest known wooden sculpture — a nine-foot-tall totem pole thousands of years old — looms over a hushed chamber of an obscure Russian museum in the Ural Mountains, not far from the Siberian border. As mysterious as the huge stone figures of Easter Island, the Shigir Idol, as it is called, is a landscape of uneasy spirits that baffles the modern onlooker.

When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency. Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck was born in 1928 to anarchist parents who left him to spend the majority of his formative years with foster parents. His father was murdered in Auschwitz. As his mother was detained, he grew up stateless, hiding from the Gestapo in occupied France. All the while, he taught himself mathematics from books and before his twentieth birthday had re-discovered for himself a proof of the

Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck was born in 1928 to anarchist parents who left him to spend the majority of his formative years with foster parents. His father was murdered in Auschwitz. As his mother was detained, he grew up stateless, hiding from the Gestapo in occupied France. All the while, he taught himself mathematics from books and before his twentieth birthday had re-discovered for himself a proof of the  Claudia Sahm over at INET:

Claudia Sahm over at INET: Now an academic classic, Orientalism was at first an unlikely best seller. Begun just as the Watergate hearings were nearing their end and published in 1978, it opens with a stark cameo of the gutted buildings of civil-war Beirut. Then, in a few paragraphs, readers are whisked off to the history of an obscure academic discipline from the Romantic era. Chapters jump from 19th-century fiction to the opéra bouffe of the American news cycle and the sordid doings of Henry Kissinger. Unless one had already been reading Edward Said or was familiar with the writings of the historian William Appleman Williams on empire “as a way of life” or the poetry of Lamartine, the choice of source materials might seem confusing or overwhelming. And so it did to the linguists and historians who fumed over the book’s success. For half of its readers, the book was a triumph, for the other half a scandal, but no one could ignore it.

Now an academic classic, Orientalism was at first an unlikely best seller. Begun just as the Watergate hearings were nearing their end and published in 1978, it opens with a stark cameo of the gutted buildings of civil-war Beirut. Then, in a few paragraphs, readers are whisked off to the history of an obscure academic discipline from the Romantic era. Chapters jump from 19th-century fiction to the opéra bouffe of the American news cycle and the sordid doings of Henry Kissinger. Unless one had already been reading Edward Said or was familiar with the writings of the historian William Appleman Williams on empire “as a way of life” or the poetry of Lamartine, the choice of source materials might seem confusing or overwhelming. And so it did to the linguists and historians who fumed over the book’s success. For half of its readers, the book was a triumph, for the other half a scandal, but no one could ignore it.

James Meadway in OpenDemocracy:

James Meadway in OpenDemocracy: Thomas Moynihan in Aeon:

Thomas Moynihan in Aeon: Alexander Zevin in New Left Review:

Alexander Zevin in New Left Review: Erica Eisen in Boston Review:

Erica Eisen in Boston Review: Aside from the flicker of fame that followed City of Quartz, Davis has managed to largely avoid the limelight for nearly four decades, despite receiving a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship, a Lannan Literary Award, and many other honors along the way. For his devoted readers, part of his appeal is surely found in his writing style, which though forceful, self-assured, and playful, is also unapologetically precise, even scientific, making full use of a century-and-a-half’s worth of Marxist vocabulary. And part of it is his seemingly dour and idiosyncratic interests, which have led him to write books about the history of the car bomb, developmental patterns in contemporary slums, and the role of El Niño famines in nineteenth-century political economy.

Aside from the flicker of fame that followed City of Quartz, Davis has managed to largely avoid the limelight for nearly four decades, despite receiving a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship, a Lannan Literary Award, and many other honors along the way. For his devoted readers, part of his appeal is surely found in his writing style, which though forceful, self-assured, and playful, is also unapologetically precise, even scientific, making full use of a century-and-a-half’s worth of Marxist vocabulary. And part of it is his seemingly dour and idiosyncratic interests, which have led him to write books about the history of the car bomb, developmental patterns in contemporary slums, and the role of El Niño famines in nineteenth-century political economy.