Safina Nabi in The Christian Science Monitor:

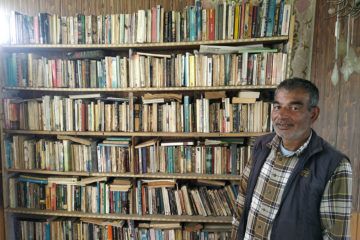

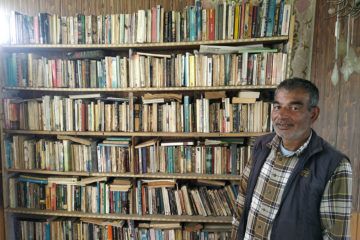

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

As Mr. Oata, dressed in a warm shirt and vest, walks me through his library I scan the names on the shelves. “Only Time Will Tell” and “The Sins of the Father,” by English novelist Jeffrey Archer. Next to them is Paulo Coelho, from Brazil. There are books by Jane Austen, Dan Brown, and Majgull Axelsson, a Swedish journalist. He speaks hesitantly, in a soft voice. But once he starts chatting about books, his voice overflows with enthusiasm.

Born in Kashmir, the eldest son of a plumber and a housewife, he left home at 16 in search of work to support his family. He moved across India, from one tourist destination to the next, selling Kashmiri arts and crafts. He still regrets not completing his formal education. Now and then, he noticed tourists at his stall holding books. One day, a man handed one to Mr. Oata, who asked him to summarize its contents. From then on, he asked book browsers if they’d be willing to swap, and tell him what the story was about – “and they would do it happily.” Over the years, he moved to India’s southeast, then west to Karnataka, selling jewelry, shawls, rugs, and hand-embroidered bags. Over time, he collected hundreds of books, mostly by international authors, and created his first small library. But he yearned to come back to the Kashmir Valley. So after much deliberation, he packed his books and went home in 2007. “I feel writers are always alive forever through their books, even after death, and for me that is such an interesting aspect,” Mr. Oata says, adding that his books are his “most precious possession.” “Though I cannot read, I can remember most of the books: their theme, the name of the author, and the country that the author belonged to,” he says. “I have remembered it all by remembering the color of the book, its cover page, and symbols.”

More here.

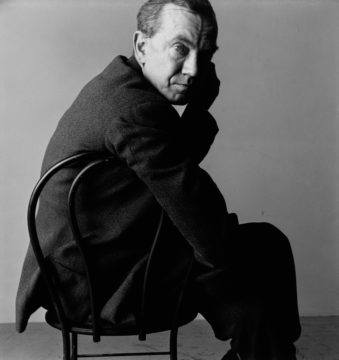

“The first thing I remember is sitting in a pram at the top of a hill with a dead dog lying at my feet.” So opens an early chapter of a memoir by Graham Greene, who is viewed by some—including Richard Greene (no relation), the author of a new biography of Graham, “The Unquiet Englishman” (Norton)—as one of the most important British novelists of his already extraordinary generation. (It included George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, Elizabeth Bowen.) The dog, Graham’s sister’s pug, had just been run over, and the nanny couldn’t think of how to get the carcass home other than to stow it in the carriage with the baby. If that doesn’t suffice to set the tone for the rather lurid events of Greene’s life, one need only turn the page, to find him, at five or so, watching a man run into a local almshouse to slit his own throat. Around that time, Greene taught himself to read, and he always remembered the cover illustration of the first book to which he gained admission. It showed, he said, “a boy, bound and gagged, dangling at the end of a rope inside a well with water rising above his waist.”

“The first thing I remember is sitting in a pram at the top of a hill with a dead dog lying at my feet.” So opens an early chapter of a memoir by Graham Greene, who is viewed by some—including Richard Greene (no relation), the author of a new biography of Graham, “The Unquiet Englishman” (Norton)—as one of the most important British novelists of his already extraordinary generation. (It included George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell, Elizabeth Bowen.) The dog, Graham’s sister’s pug, had just been run over, and the nanny couldn’t think of how to get the carcass home other than to stow it in the carriage with the baby. If that doesn’t suffice to set the tone for the rather lurid events of Greene’s life, one need only turn the page, to find him, at five or so, watching a man run into a local almshouse to slit his own throat. Around that time, Greene taught himself to read, and he always remembered the cover illustration of the first book to which he gained admission. It showed, he said, “a boy, bound and gagged, dangling at the end of a rope inside a well with water rising above his waist.”

When researching my bio-fictional novel about Emily Dickinson, I read the erotic letters between Emily’s brother, Austin, and his mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd. The letters were direct, steamy, and quite mad in parts—for their paranoia and plotting—and I thought uncomfortably, No one on earth should be privy to these kinds of intimacies! When I first read Joyce’s letters to Nora, I was similarly gobsmacked. I recognized the frank language and the explicit, obscene imaginings. I liked, too, the intimate, tender spillover into poetic trances. But I was made wide-eyed, particularly, by his obsession with defecation as an erotic act. There are numerous references to Joyce’s love for what he calls “the most shameful and filthy act of the body.” Over and over he refers to being turned on by “shit,” “farts,” and “brown stains.” Even now, more familiar with the letters, I squirm a bit when I read this from Joyce to Nora: “The smallest things give me a great cockstand—a whorish movement of your mouth, a little brown stain on the seat of your white drawers, a sudden dirty word spluttered out by your wet lips, a sudden immodest noise made by you behind and then a bad smell slowly curling up out of your backside. At such moments I feel mad to do it in some filthy way, to feel your hot lecherous lips sucking away at me.” This was an utterly private sharing between lovers, the things they traded to bind themselves together, and Joyce’s fetish ought not bother me at all, as I shouldn’t know about it. Although, anyone who has read Molly Bloom’s wondrous speech in the Penelope episode of Ulysses might reasonably guess at Joyce’s delight in the coprophilic. When Molly wants money, she plans to let Bloom kiss her bottom, saying he can “stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part then Ill tell him I want £1.”

When researching my bio-fictional novel about Emily Dickinson, I read the erotic letters between Emily’s brother, Austin, and his mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd. The letters were direct, steamy, and quite mad in parts—for their paranoia and plotting—and I thought uncomfortably, No one on earth should be privy to these kinds of intimacies! When I first read Joyce’s letters to Nora, I was similarly gobsmacked. I recognized the frank language and the explicit, obscene imaginings. I liked, too, the intimate, tender spillover into poetic trances. But I was made wide-eyed, particularly, by his obsession with defecation as an erotic act. There are numerous references to Joyce’s love for what he calls “the most shameful and filthy act of the body.” Over and over he refers to being turned on by “shit,” “farts,” and “brown stains.” Even now, more familiar with the letters, I squirm a bit when I read this from Joyce to Nora: “The smallest things give me a great cockstand—a whorish movement of your mouth, a little brown stain on the seat of your white drawers, a sudden dirty word spluttered out by your wet lips, a sudden immodest noise made by you behind and then a bad smell slowly curling up out of your backside. At such moments I feel mad to do it in some filthy way, to feel your hot lecherous lips sucking away at me.” This was an utterly private sharing between lovers, the things they traded to bind themselves together, and Joyce’s fetish ought not bother me at all, as I shouldn’t know about it. Although, anyone who has read Molly Bloom’s wondrous speech in the Penelope episode of Ulysses might reasonably guess at Joyce’s delight in the coprophilic. When Molly wants money, she plans to let Bloom kiss her bottom, saying he can “stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part then Ill tell him I want £1.” After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

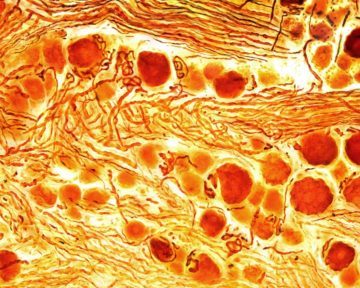

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room. Some studies estimate that a large proportion of the population in Europe and the United States — as high as 50% — experiences chronic pain

Some studies estimate that a large proportion of the population in Europe and the United States — as high as 50% — experiences chronic pain In 1987 I had a sort-of-girlfriend, let us call her Nikki, who came from a devout Catholic working-class family of French-Canadian heritage. When I met her she had just returned from a family pilgrimage to Medjugorje, in post-Tito, pre-war Yugoslavia, where her mother and father had hoped to see the famed weeping statue of Mary, fluentis lacrimis. I knew enough of Slavic etymology already to be intrigued by that town’s name, like the young W. V. O. Quine, who once found himself on a street in Prague that started with the preposition Pod, and thought: “I must be at the bottom of something”. The Medju clearly meant the place was between or amidst something or other, but what exactly?

In 1987 I had a sort-of-girlfriend, let us call her Nikki, who came from a devout Catholic working-class family of French-Canadian heritage. When I met her she had just returned from a family pilgrimage to Medjugorje, in post-Tito, pre-war Yugoslavia, where her mother and father had hoped to see the famed weeping statue of Mary, fluentis lacrimis. I knew enough of Slavic etymology already to be intrigued by that town’s name, like the young W. V. O. Quine, who once found himself on a street in Prague that started with the preposition Pod, and thought: “I must be at the bottom of something”. The Medju clearly meant the place was between or amidst something or other, but what exactly?  Last winter, Ray Harinarain, a heating and air-conditioning contractor living in Brooklyn, flew home to Guyana with several thousand dollars in cash. Escorted by armed guards, he drove from village to village, examining wild finches like some veterinary talent scout. The birds had been captured in nearby forests using glue strips or nets. Some were visibly frightened by life in captivity. A few had begun the halting process of habituation, waiting on their perches instead of bashing against the bars. And the “baddest” birds—which in Guyanese patois means the best birds—were just about ready to burst into song.

Last winter, Ray Harinarain, a heating and air-conditioning contractor living in Brooklyn, flew home to Guyana with several thousand dollars in cash. Escorted by armed guards, he drove from village to village, examining wild finches like some veterinary talent scout. The birds had been captured in nearby forests using glue strips or nets. Some were visibly frightened by life in captivity. A few had begun the halting process of habituation, waiting on their perches instead of bashing against the bars. And the “baddest” birds—which in Guyanese patois means the best birds—were just about ready to burst into song. A good many people claim to be “free speech absolutists,” but I’m not sure whether they really are. Push an absolutist hard enough with edge cases and you typically discover that they do indeed draw lines beyond which speech may not be permitted to go. (How many celebrants of free speech advocate the elimination of libel and slander laws?) But even if true absolutists exist, some of the people most often cited in support of free speech certainly were not so absolute. And there may be useful lessons for us in that.

A good many people claim to be “free speech absolutists,” but I’m not sure whether they really are. Push an absolutist hard enough with edge cases and you typically discover that they do indeed draw lines beyond which speech may not be permitted to go. (How many celebrants of free speech advocate the elimination of libel and slander laws?) But even if true absolutists exist, some of the people most often cited in support of free speech certainly were not so absolute. And there may be useful lessons for us in that. Arefa Johari was

Arefa Johari was Flash forward to the present day, as the art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator, “content.”

Flash forward to the present day, as the art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator, “content.” Dalton is one

Dalton is one  Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Nadia Marzouki in Boston Review:

Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Nadia Marzouki in Boston Review: Hannah Levintova in Mother Jones:

Hannah Levintova in Mother Jones: Maya Adereth interviews Felipe González in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth interviews Felipe González in Phenomenal World: Sam Moyn in The New Republic:

Sam Moyn in The New Republic: