Man and Boy

I

‘Catch the old one first’

(My father’s joke was also old, and heavy

And predictable). ‘then the young ones

Will all follow, and Bob’s your uncle.’

On slow bright river evenings, the sweet time

Made him afraid we’d take too much for granted

And so our spirits must be lightly checked.

Blessed be down-to-earth! Blessed be highs!

Blessed be the attachment of dumb love

In that broad-backed, low-set man

Who feared debt all his life, but now and then

Could make a splash like the salmon he said he was

‘A big as a wee pork pig by the sound of it’.

II

In earshot of the pool where the salmon jumped

Back through its own unheard concentric soundwaves

A mower leans forever on his scythe.

He has mown himself to the center of the field

And stands in a final perfect ring

of sunlit stubble.

‘Go and tell your father,’ the mower says

(He said it to my father who told me),

‘I have it mowed as clean as a new sixpence.’

My father is a barefoot boy with news,

Running at eye-level with weeds and stooks

On the afternoon of his own father’s death.

The open, black half of the half-door waits.

I feel much heat and hurry in the air.

I feel his legs and quick heels far away

And strange as my own—when he will piggyback me

At a great height, light-headed and thin-boned,

Like a witless elder rescued from the fire.

by Seamus Heaney

from Seeing Things

Faber & Faber, 1991

DIGITAL-DATA PRODUCTION

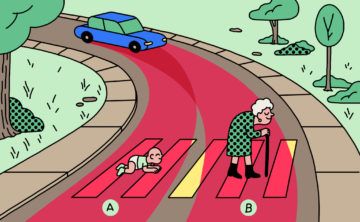

DIGITAL-DATA PRODUCTION Where do you place the boundary between “science” and “pseudoscience”? The question is more than academic. The answers we give have consequences—in part because, as health policy scholar Timothy Caulfield

Where do you place the boundary between “science” and “pseudoscience”? The question is more than academic. The answers we give have consequences—in part because, as health policy scholar Timothy Caulfield  W

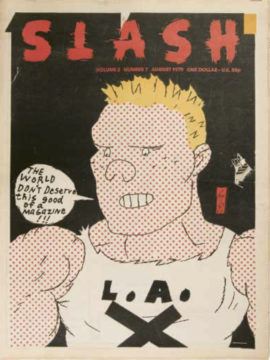

W According to Panter, he didn’t set out to create Jimbo, “he just showed up.” Jimbo made his first public appearance in the punk magazine Slash in 1977 and his cover debut two years later. His pug-nosed mug moved to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s radical art-comics anthology Raw in 1981; some of Jimbo’s stories there made up the first Raw One-Shot, a spin-off of the periodical, the following year. He joined an ensemble cast in Panter’s Cola Madnes, written in 1983 but not published until 2000, and landed his first full-length book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, in 1988, published by Raw and Pantheon. Jimbo has since starred in four issues of a self-titled comic published by Zongo in the nineties and stood in for Dante in two illuminated-manuscripts-cum-comic-books: Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). He is, as you read these words, being sent out into fresh adventures by Panter’s fervid imagination and tireless pen.

According to Panter, he didn’t set out to create Jimbo, “he just showed up.” Jimbo made his first public appearance in the punk magazine Slash in 1977 and his cover debut two years later. His pug-nosed mug moved to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s radical art-comics anthology Raw in 1981; some of Jimbo’s stories there made up the first Raw One-Shot, a spin-off of the periodical, the following year. He joined an ensemble cast in Panter’s Cola Madnes, written in 1983 but not published until 2000, and landed his first full-length book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, in 1988, published by Raw and Pantheon. Jimbo has since starred in four issues of a self-titled comic published by Zongo in the nineties and stood in for Dante in two illuminated-manuscripts-cum-comic-books: Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). He is, as you read these words, being sent out into fresh adventures by Panter’s fervid imagination and tireless pen. Shortly after September 11, 2001, Bruno Latour for example

Shortly after September 11, 2001, Bruno Latour for example  I am a non-white Mizrahi Jewish academic who has been studying Israel/Palestine and the history of Jews in the Middle East for two decades. My family hails from Ottoman Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and the Greek islands of Zakynthos and Corfu. All too many of us were murdered by Nazi Génocidaires (and rest assured that we will not forget or forgive). Precisely because of this scholarly and biographic background I was embarrassed to read the

I am a non-white Mizrahi Jewish academic who has been studying Israel/Palestine and the history of Jews in the Middle East for two decades. My family hails from Ottoman Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and the Greek islands of Zakynthos and Corfu. All too many of us were murdered by Nazi Génocidaires (and rest assured that we will not forget or forgive). Precisely because of this scholarly and biographic background I was embarrassed to read the  The largest animals that have ever existed on our planet descended from a miniature deer-like creature that walked on four legs in the swamps of ancient India.

The largest animals that have ever existed on our planet descended from a miniature deer-like creature that walked on four legs in the swamps of ancient India. Like other artists, the actor is a kind of shaman. If the audience is lucky, we go with this emotional magician to other worlds and other versions of ourselves. Our enchantment or immersion into another world is not just theoretical, but sensory and emotional. How do actor and audience achieve this shared mysterious transportation? This shared ritual draws upon a kind of sixth sense, the imagination. The actor’s imagination has gone into emotional territories of intense feeling before us. Now they guide us like a psychopomp into those emotional territories by recreating them in front of us.

Like other artists, the actor is a kind of shaman. If the audience is lucky, we go with this emotional magician to other worlds and other versions of ourselves. Our enchantment or immersion into another world is not just theoretical, but sensory and emotional. How do actor and audience achieve this shared mysterious transportation? This shared ritual draws upon a kind of sixth sense, the imagination. The actor’s imagination has gone into emotional territories of intense feeling before us. Now they guide us like a psychopomp into those emotional territories by recreating them in front of us. I HAVE NEVER BEEN ABLE

I HAVE NEVER BEEN ABLE In 2014 researchers at the MIT Media Lab designed an experiment called

In 2014 researchers at the MIT Media Lab designed an experiment called  Charlie Tyson reviews Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Charlie Tyson reviews Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Ari Linden in Public Books:

Ari Linden in Public Books: