Manjit Kumar at The Guardian:

With the light touch of a skilled storyteller, Rovelli reveals that Heisenberg had been wrestling with the inner workings of the quantum atom in which electrons travel around the nucleus only in certain orbits, at certain distances, with certain precise energies before magically “leaping” from one orbit to another. Among the unsolved questions he was grappling with on Helgoland were: why only these orbits? Why only certain orbital leaps? As he tried to overcome the failure of existing formulas to replicate the intensity of the light emitted as an electron leapt between orbits, Heisenberg made an astonishing leap of his own. He decided to focus only on those quantities that are observable – the light an atom emits when an electron jumps. It was a strange idea but one that, as Rovelli points out, made it possible to account for all the recalcitrant facts and to develop a mathematically coherent theory of the atomic world.

With the light touch of a skilled storyteller, Rovelli reveals that Heisenberg had been wrestling with the inner workings of the quantum atom in which electrons travel around the nucleus only in certain orbits, at certain distances, with certain precise energies before magically “leaping” from one orbit to another. Among the unsolved questions he was grappling with on Helgoland were: why only these orbits? Why only certain orbital leaps? As he tried to overcome the failure of existing formulas to replicate the intensity of the light emitted as an electron leapt between orbits, Heisenberg made an astonishing leap of his own. He decided to focus only on those quantities that are observable – the light an atom emits when an electron jumps. It was a strange idea but one that, as Rovelli points out, made it possible to account for all the recalcitrant facts and to develop a mathematically coherent theory of the atomic world.

more here.

“A deep-end girl,” he called himself, not one “minnying along the sidewalk of life.”

“A deep-end girl,” he called himself, not one “minnying along the sidewalk of life.” Maggie O’Farrell found the prospect of writing the central scenes of her

Maggie O’Farrell found the prospect of writing the central scenes of her  ROAD WARRIOR In the month since the publication of her memoir, “

ROAD WARRIOR In the month since the publication of her memoir, “ Edward Said was our prince,” the Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif recently said in a conversation reflecting on the Palestinian public intellectual’s life and writings. An incomparable thinker, Said is credited with founding postcolonial studies, penning histories of cultural representation and “the Other,” and, in so doing, upending the Anglo-American academy. His Orientalism, published in 1978, is among the most cited books in modern history, by

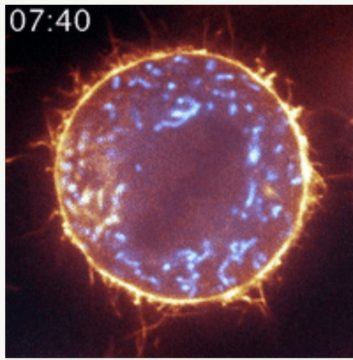

Edward Said was our prince,” the Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif recently said in a conversation reflecting on the Palestinian public intellectual’s life and writings. An incomparable thinker, Said is credited with founding postcolonial studies, penning histories of cultural representation and “the Other,” and, in so doing, upending the Anglo-American academy. His Orientalism, published in 1978, is among the most cited books in modern history, by  In a landmark study, a team led by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania has discovered—and filmed—the molecular details of how a cell, just before it divides in two, shuffles important internal components called mitochondria to distribute them evenly to its two daughter cells.

In a landmark study, a team led by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania has discovered—and filmed—the molecular details of how a cell, just before it divides in two, shuffles important internal components called mitochondria to distribute them evenly to its two daughter cells. I wrote about poet

I wrote about poet

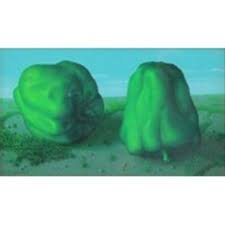

Charles Patterson’s Peppers, 1953, presents a pair of gigantic green peppers against an unnaturally manicured landscape. Textured with a kind of tense muscularity, the fruits convey the sense they might burst forth from the board and, as such, are more than a little bit threatening. This slightly off-kilter depiction of quotidian objects, rendered with painterly exactitude, seems precisely to fit Barr’s characterization. But in another piece of Patterson’s—The Room, 1958—the stagey improbability and expressionless faces of its five assembled characters combine to much less disconcerting effect. A wide-eyed female figure reclines on a divan while a man and woman struggle with a large dog that may wish to chase the cat dashing beneath the studio couch. An open curtain behind the group reveals an elderly woman robing a skeletal figure in a bath. If the realm of unconscious reverie is being evoked, it is done with a deliberateness that recalls the clichés of an overly earnest Surrealism—locomotives emerging from fireplaces, elephants on bony stilts, and the like.

Charles Patterson’s Peppers, 1953, presents a pair of gigantic green peppers against an unnaturally manicured landscape. Textured with a kind of tense muscularity, the fruits convey the sense they might burst forth from the board and, as such, are more than a little bit threatening. This slightly off-kilter depiction of quotidian objects, rendered with painterly exactitude, seems precisely to fit Barr’s characterization. But in another piece of Patterson’s—The Room, 1958—the stagey improbability and expressionless faces of its five assembled characters combine to much less disconcerting effect. A wide-eyed female figure reclines on a divan while a man and woman struggle with a large dog that may wish to chase the cat dashing beneath the studio couch. An open curtain behind the group reveals an elderly woman robing a skeletal figure in a bath. If the realm of unconscious reverie is being evoked, it is done with a deliberateness that recalls the clichés of an overly earnest Surrealism—locomotives emerging from fireplaces, elephants on bony stilts, and the like.

Imagine two people with exactly the same innate abilities, but one is born into a wealthy family and the other is born into poverty. Or two people born into similar circumstances, but one is paralyzed in a freak accident in childhood while the other grows up in perfect health. Is this fair? We live in a society that values some kind of “equality” — “All men are created equal” — without ever quite specifying what we mean. Elizabeth Anderson is a leading philosopher of equality, and we talk about what really matters about this notion. This leads to down-to-earth issues about employment and the work ethic, and how it all ties into modern capitalism. We end up agreeing that a leisure society would be great, but at the moment there’s plenty of work to be done.

Imagine two people with exactly the same innate abilities, but one is born into a wealthy family and the other is born into poverty. Or two people born into similar circumstances, but one is paralyzed in a freak accident in childhood while the other grows up in perfect health. Is this fair? We live in a society that values some kind of “equality” — “All men are created equal” — without ever quite specifying what we mean. Elizabeth Anderson is a leading philosopher of equality, and we talk about what really matters about this notion. This leads to down-to-earth issues about employment and the work ethic, and how it all ties into modern capitalism. We end up agreeing that a leisure society would be great, but at the moment there’s plenty of work to be done. Even though China and Russia started inoculating their citizens last year before publishing the efficacy results from their phase 3 clinical trials, which inevitably raised legitimate concerns, these vaccines have since been proven safe and efficient. The medical journal The Lancet published in February results from late-stage trials showing that Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine, has an efficacy rate of 91.6 percent. At least twenty-five countries around the world, meanwhile, have approved and are administering Sinopharm, one of the Chinese vaccines, with seemingly successful results.

Even though China and Russia started inoculating their citizens last year before publishing the efficacy results from their phase 3 clinical trials, which inevitably raised legitimate concerns, these vaccines have since been proven safe and efficient. The medical journal The Lancet published in February results from late-stage trials showing that Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine, has an efficacy rate of 91.6 percent. At least twenty-five countries around the world, meanwhile, have approved and are administering Sinopharm, one of the Chinese vaccines, with seemingly successful results. But Robinson’s Christianity manifests as more than a formal approach to experience—the particulars of her belief do matter, and they serve as a foundation for the representation of American racism in the Gilead novels. With John Calvin, she shares the conviction that there is “a visionary quality to all experience” and that God animates, at every moment, all of creation. This endows that creation with immanence and revelatory potential. She believes in the existence of souls, mysterious and unaccountable and equal, which profoundly influences how she engages the material reality of racist institutions and social practices. She believes, like Calvin and the contemporary Black theologian Reggie L. Williams, that each encounter with another person is an encounter with an image of God, in effect God himself, thus placing an immense weight on the treatment of others, surpassing even the Golden Rule. Even if a man is trying to kill you, “you owe him everything.” As Calvin does, she believes that each encounter with another person is a question that God is asking of you. In a recent lecture, she described one of God’s goals for creation—which, by implication, should be a human goal—as “human flourishing.” “Flourishing” is a startling word. Its pursuit demands far more than tolerance, or even civic equality: it demands a passionate devotion to others, regardless of your connections through family, country, race or religion. For her, good and evil are relational, social—not solely internal matters. Christianity, she has said, is an ethic, not an identity.

But Robinson’s Christianity manifests as more than a formal approach to experience—the particulars of her belief do matter, and they serve as a foundation for the representation of American racism in the Gilead novels. With John Calvin, she shares the conviction that there is “a visionary quality to all experience” and that God animates, at every moment, all of creation. This endows that creation with immanence and revelatory potential. She believes in the existence of souls, mysterious and unaccountable and equal, which profoundly influences how she engages the material reality of racist institutions and social practices. She believes, like Calvin and the contemporary Black theologian Reggie L. Williams, that each encounter with another person is an encounter with an image of God, in effect God himself, thus placing an immense weight on the treatment of others, surpassing even the Golden Rule. Even if a man is trying to kill you, “you owe him everything.” As Calvin does, she believes that each encounter with another person is a question that God is asking of you. In a recent lecture, she described one of God’s goals for creation—which, by implication, should be a human goal—as “human flourishing.” “Flourishing” is a startling word. Its pursuit demands far more than tolerance, or even civic equality: it demands a passionate devotion to others, regardless of your connections through family, country, race or religion. For her, good and evil are relational, social—not solely internal matters. Christianity, she has said, is an ethic, not an identity.