Category: Recommended Reading

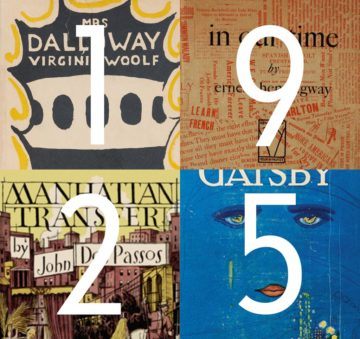

Was 1925 Literary Modernism’s Most Important Year?

Ben Libman at the New York Times:

“An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking & ultimately nauseating.” So goes Virginia Woolf’s well-known complaint about “Ulysses,” scribbled into her diary before she had finished reading it. Her disparagement is catnip to those many critics who like to view “Mrs. Dalloway” — that other uber-famous, if more lapidary, modernist novel that spans the course of a single day — as Woolf’s rejoinder to Joyce. More than that, though, it tells us something important about our literary history. Nineteen twenty-two, the year of “Ulysses,” may well be ground zero for the explosion of modernism in literature. But the resultant shock wave is better captured by another year: 1925, that of “Mrs. Dalloway” and several other works, all now in the spotlight in 2021, as they emerge from under copyright.

“An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are, how egotistic, insistent, raw, striking & ultimately nauseating.” So goes Virginia Woolf’s well-known complaint about “Ulysses,” scribbled into her diary before she had finished reading it. Her disparagement is catnip to those many critics who like to view “Mrs. Dalloway” — that other uber-famous, if more lapidary, modernist novel that spans the course of a single day — as Woolf’s rejoinder to Joyce. More than that, though, it tells us something important about our literary history. Nineteen twenty-two, the year of “Ulysses,” may well be ground zero for the explosion of modernism in literature. But the resultant shock wave is better captured by another year: 1925, that of “Mrs. Dalloway” and several other works, all now in the spotlight in 2021, as they emerge from under copyright.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Revisions

Before the poet was a poet

nothing was reworked:

not the smudge of ink on twelve sets of clothes

not the fearsome top berth on the train

not a room full of boxes and dull windows

not the cat that left its kittens and afterbirth in a pair of jeans

not doubt.

Before the poet was a poet

everything had a place:

six years were six years ……… parallel lines followed rules

like obedient children

[the Dewey Decimal System]

………………………………………………..homes remained where they’d

been left.

Before the poet was a poet

many things went unseen:

clouds sometimes wheedled a ray out of the sun parents kept

…… photographs under their

pillows letters never said everything they wanted to lectures

…… were interrupted by a

commotion of leaves every step was upon a blind spot.

by Sridala Swami

from Escape Artist

Aleph Book Co., New Delhi, 2014

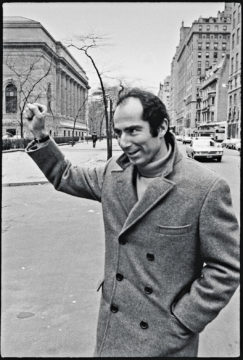

The life of Philip Roth and the art of literary survival

Christian Lorentzen in Bookforum:

When Roth died at age eighty-five in 2018, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times that it was the end of a cultural era. Roth was “the last front-rank survivor of a generation of fecund and authoritative and, yes, white and male novelists.” Never mind that at least four other major American novelists born in the 1930s—DeLillo, McCarthy, Morrison, Pynchon—were still alive. Forget about pigeonholing as white and male an author who at the beginning of his career was invited to sit beside Ralph Ellison on panels about “minority writing”—because Jews were still at the margins. No matter that the modes that sustained Roth—autobiography with comic exaggeration, autobiographical metafiction, historical fiction of the recent past—are the modes that define the current moment. Roth was not an end point but the beginning of the present. There had been fluke golden boys before him, like Fitzgerald and Mailer, but Roth, twenty-six when he won the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus in 1960, reset the template for the prodigy author in the age of television, going at it with Mike Wallace in prime time. The morning before he spoke to Wallace he gave an interview to a young reporter for the New York Post, who asked him about a critic who’d called his book “an exhibition of Jewish self-hate.” A few weeks later the piece turned up in the mail Roth received from his clipping service while he was staying in Rome. He was quoted as saying the critic ought to “write a book about why he hates me. It might give insights into me and him, too.” “I decided then and there,” his biographer Blake Bailey quotes him saying at the time, “to give up a public career.”

When Roth died at age eighty-five in 2018, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times that it was the end of a cultural era. Roth was “the last front-rank survivor of a generation of fecund and authoritative and, yes, white and male novelists.” Never mind that at least four other major American novelists born in the 1930s—DeLillo, McCarthy, Morrison, Pynchon—were still alive. Forget about pigeonholing as white and male an author who at the beginning of his career was invited to sit beside Ralph Ellison on panels about “minority writing”—because Jews were still at the margins. No matter that the modes that sustained Roth—autobiography with comic exaggeration, autobiographical metafiction, historical fiction of the recent past—are the modes that define the current moment. Roth was not an end point but the beginning of the present. There had been fluke golden boys before him, like Fitzgerald and Mailer, but Roth, twenty-six when he won the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus in 1960, reset the template for the prodigy author in the age of television, going at it with Mike Wallace in prime time. The morning before he spoke to Wallace he gave an interview to a young reporter for the New York Post, who asked him about a critic who’d called his book “an exhibition of Jewish self-hate.” A few weeks later the piece turned up in the mail Roth received from his clipping service while he was staying in Rome. He was quoted as saying the critic ought to “write a book about why he hates me. It might give insights into me and him, too.” “I decided then and there,” his biographer Blake Bailey quotes him saying at the time, “to give up a public career.”

At the time the remark might have been wishful thinking. In retrospect it’s laughably disingenuous. Far from retreating from public view, Roth embarked on a decades-long campaign of public-image control. He always hated critics, but reserved his vitriol for lengthy letters to the editor (one to the New York Review of Books in 1974 suggested that Times staff critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt be sacked and his job be filled by an annual contest among undergraduates) or fictionalized rebukes where he and his alter-egos had the last word.

More here.

Biologist Marie Fish Catalogued the Sounds of the Ocean for the World to Hear

Ben Goldfarb in Smithsonian:

Among the many puzzles that confronted American sailors during World War II, few were as vexing as the sound of phantom enemies. Especially in the war’s early days, submarine crews and sonar operators listening for Axis vessels were often baffled by what they heard. When the USS Salmon surfaced to search for the ship whose rumbling propellers its crew had detected off the Philippines coast on Christmas Eve 1941, the submarine found only an empty expanse of moonlit ocean. Elsewhere in the Pacific, the USS Tarpon was mystified by a repetitive clanging and the USS Permit by what crew members described as the sound of “hammering on steel.” In the Chesapeake Bay, the clangor—likened by one sailor to “pneumatic drills tearing up a concrete sidewalk”—was so loud it threatened to detonate defensive mines and sink friendly ships.

Among the many puzzles that confronted American sailors during World War II, few were as vexing as the sound of phantom enemies. Especially in the war’s early days, submarine crews and sonar operators listening for Axis vessels were often baffled by what they heard. When the USS Salmon surfaced to search for the ship whose rumbling propellers its crew had detected off the Philippines coast on Christmas Eve 1941, the submarine found only an empty expanse of moonlit ocean. Elsewhere in the Pacific, the USS Tarpon was mystified by a repetitive clanging and the USS Permit by what crew members described as the sound of “hammering on steel.” In the Chesapeake Bay, the clangor—likened by one sailor to “pneumatic drills tearing up a concrete sidewalk”—was so loud it threatened to detonate defensive mines and sink friendly ships.

Once the war ended, the Navy, which had begun to suspect that sea creatures were, in fact, behind the cacophony, turned to investigating the problem. To lead the effort it chose a scientist who, though famous in her day, has been largely overlooked by posterity: Marie Poland Fish, who would found the field of marine bioacoustics. By the time the Navy brought her on board in 1946, Fish was already a celebrated biologist. Born in 1900, Marie Poland—known to friends as Bobbie, on account of her flapper hairstyle—grew up in Paterson, New Jersey, and was a premedical student at Smith College. Upon graduating in 1921, though, she’d turned to the sea to spend more time with Charles Fish, a young plankton scientist whom she’d met while conducting cancer research at a laboratory on Long Island. In 1923, after spending a year as Charles’ research assistant, she took a job with the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries in Massachusetts; that same year, they married.

More here.

Friday, March 19, 2021

Literary Scholars Should Argue Better

Hannah Walser in the Chronicle of Higher Education:

A couple of weeks ago, I attended an interdisciplinary seminar featuring work in progress on law and humanities. After the guest presenter finished reading his chapter draft, the floor opened for discussion: Legal scholars pushed for more terminological precision, historians suggested alternative timelines, political scientists offered comparative context that called some of the author’s conclusions into question. It wasn’t until the frank, fun, productive conversation had wrapped up that I put my finger on what had been missing. Where was the praise?

A couple of weeks ago, I attended an interdisciplinary seminar featuring work in progress on law and humanities. After the guest presenter finished reading his chapter draft, the floor opened for discussion: Legal scholars pushed for more terminological precision, historians suggested alternative timelines, political scientists offered comparative context that called some of the author’s conclusions into question. It wasn’t until the frank, fun, productive conversation had wrapped up that I put my finger on what had been missing. Where was the praise?

In my own field, literary studies, almost every talk involves some kind of panegyric, from an effusive speaker introduction to a closing moment of gratitude for the power and timeliness of the event. In between, there’s a very good chance that audience members will begin their questions and comments with an expression of devout gratitude. Thank you so much for this beautiful, this important, this fascinating, this marvelous talk!

More here.

Quantum Mischief Rewrites the Laws of Cause and Effect

Natalie Wolchover in Quanta:

Alice and Bob, the stars of so many thought experiments, are cooking dinner when mishaps ensue. Alice accidentally drops a plate; the sound startles Bob, who burns himself on the stove and cries out. In another version of events, Bob burns himself and cries out, causing Alice to drop a plate.

Alice and Bob, the stars of so many thought experiments, are cooking dinner when mishaps ensue. Alice accidentally drops a plate; the sound startles Bob, who burns himself on the stove and cries out. In another version of events, Bob burns himself and cries out, causing Alice to drop a plate.

Over the last decade, quantum physicists have been exploring the implications of a strange realization: In principle, both versions of the story can happen at once. That is, events can occur in an indefinite causal order, where both “A causes B” and “B causes A” are simultaneously true.

“It sounds outrageous,” admitted Časlav Brukner, a physicist at the University of Vienna.

The possibility follows from the quantum phenomenon known as superposition, where particles maintain all possible realities simultaneously until the moment they’re measured. In labs in Austria, China, Australia and elsewhere, physicists observe indefinite causal order by putting a particle of light (called a photon) in a superposition of two states. They then subject one branch of the superposition to process A followed by process B, and subject the other branch to B followed by A. In this procedure, known as the quantum switch, A’s outcome influences what happens in B, and vice versa; the photon experiences both causal orders simultaneously.

More here.

Meritocracy is bad

Matthew Yglesias in Slow Boring:

And if you talk to people with a curious and open mind, you’ll pretty quickly find out that New York Times reporters are really smart. So are McKinsey consultants. So are the people working at successful hedge funds. So are Ivy League professors. Probably the smartest person I know was in a great grad program in the humanities, couldn’t quite get a tenure track job because of timing and the generally lousing job market in academia, and wound up with a job in finance at a firm that is famous for hiring really smart people with unorthodox backgrounds. Our society is great at identifying smart people and giving them important or lucrative jobs.

And if you talk to people with a curious and open mind, you’ll pretty quickly find out that New York Times reporters are really smart. So are McKinsey consultants. So are the people working at successful hedge funds. So are Ivy League professors. Probably the smartest person I know was in a great grad program in the humanities, couldn’t quite get a tenure track job because of timing and the generally lousing job market in academia, and wound up with a job in finance at a firm that is famous for hiring really smart people with unorthodox backgrounds. Our society is great at identifying smart people and giving them important or lucrative jobs.

This just turns out to be an outcome that still has some problems.

More here.

Broken English is My Mother Tongue

Kuba Dorabialski in the Sydney Review of Books:

When I started school in Australia I was put in a special class for ESL children. I was horrified to learn that I couldn’t speak English. I thought I spoke English just fine. Little did I know, it was actually Broken English that I spoke.

Many years later, as an adult, I was involved in a little open mic poetry community. Someone posted a recording from one of these events, and once again I was horrified; this time by the sound of my voice. It sounded so foreign to me. So Anglo-Australian. I had dropped my guard somewhere along the way and my Broken English had given way to an Art School Anglo-Aussie English with hints of Westie.

It took a while to recover from this shock and I momentarily stopped performing my work. After a while it became apparent to me that the only way to reclaim my voice was to return to my mother tongue: Broken English.

The Doctor Will Sniff You Now

Lina Zeldovich in Nautilus:

It’s 2050 and you’re due for your monthly physical exam. Times have changed, so you no longer have to endure an orifices check, a needle in your vein, and a week of waiting for your blood test results. Instead, the nurse welcomes you with, “The doctor will sniff you now,” and takes you into an airtight chamber wired up to a massive computer. As you rest, the volatile molecules you exhale or emit from your body and skin slowly drift into the complex artificial intelligence apparatus, colloquially known as Deep Nose. Behind the scene, Deep Nose’s massive electronic brain starts crunching through the molecules, comparing them to its enormous olfactory database. Once it’s got a noseful, the AI matches your odors to the medical conditions that cause them and generates a printout of your health. Your human doctor goes over the results with you and plans your treatment or adjusts your meds.

It’s 2050 and you’re due for your monthly physical exam. Times have changed, so you no longer have to endure an orifices check, a needle in your vein, and a week of waiting for your blood test results. Instead, the nurse welcomes you with, “The doctor will sniff you now,” and takes you into an airtight chamber wired up to a massive computer. As you rest, the volatile molecules you exhale or emit from your body and skin slowly drift into the complex artificial intelligence apparatus, colloquially known as Deep Nose. Behind the scene, Deep Nose’s massive electronic brain starts crunching through the molecules, comparing them to its enormous olfactory database. Once it’s got a noseful, the AI matches your odors to the medical conditions that cause them and generates a printout of your health. Your human doctor goes over the results with you and plans your treatment or adjusts your meds.

That’s how Alexei Koulakov, a researcher at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, who studies how the human olfactory system works, envisions one possible future of our healthcare. A physicist turned neuroscientist, Koulakov is working to understand how humans perceive odors and to classify millions of volatile molecules by their “smellable” properties. He plans to catalogue the existing smells into a comprehensive artificial intelligence network. Once built, Deep Nose will be able to identify the odors of a person or any other olfactory bouquet of interest—for medical or other reasons. “It will be a chip that can diagnose or identify you,” Koulakov says. Scent uniquely identifies a person or merchandise, so Deep Nose can also help at the border patrol, sniffing travelers, cargo, or explosives. “Instead of presenting passports at the airport, you would just present yourself.” And doctor’s visits would become a breeze—literally.

More here.

Can Cyrus Vance, Jr., Nail Trump?

Jane Mayer in The New Yorker:

On February 22nd, in an office in White Plains, two lawyers handed over a hard drive to a Manhattan Assistant District Attorney, who, along with two investigators, had driven up from New York City in a heavy snowstorm. Although the exchange didn’t look momentous, it set in motion the next phase of one of the most significant legal showdowns in American history. Hours earlier, the Supreme Court had ordered former President Donald Trump to comply with a subpoena for nearly a decade’s worth of private financial records, including his tax returns. The subpoena had been issued by Cyrus Vance, Jr., the Manhattan District Attorney, who is leading the first, and larger, of two known probes into potential criminal misconduct by Trump. The second was opened, last month, by a county prosecutor in Georgia, who is investigating Trump’s efforts to undermine that state’s election results.

On February 22nd, in an office in White Plains, two lawyers handed over a hard drive to a Manhattan Assistant District Attorney, who, along with two investigators, had driven up from New York City in a heavy snowstorm. Although the exchange didn’t look momentous, it set in motion the next phase of one of the most significant legal showdowns in American history. Hours earlier, the Supreme Court had ordered former President Donald Trump to comply with a subpoena for nearly a decade’s worth of private financial records, including his tax returns. The subpoena had been issued by Cyrus Vance, Jr., the Manhattan District Attorney, who is leading the first, and larger, of two known probes into potential criminal misconduct by Trump. The second was opened, last month, by a county prosecutor in Georgia, who is investigating Trump’s efforts to undermine that state’s election results.

Vance is a famously low-key prosecutor, but he has been waging a ferocious battle. His subpoena required Trump’s accounting firm, Mazars U.S.A., to turn over millions of pages of personal and corporate records, dating from 2011 to 2019, that Trump had withheld from prosecutors and the public. Before Trump was elected, in 2016, he promised to release his tax records, as every other modern President has done, and he repeated that promise after taking office. Instead, he went to extraordinary lengths to hide the documents. The subpoena will finally give legal authorities a clear look at the former President’s opaque business empire, helping them to determine whether he committed any financial crimes. After Vance’s victory at the Supreme Court, he released a typically buttoned-up statement: “The work continues.”

If the tax records contain major revelations, the public probably won’t learn about them anytime soon: the information will likely be kept secret unless criminal charges are filed. The hard drive—which includes potentially revealing notes showing how Trump and his accountants arrived at their tax numbers—is believed to be locked in a high-security annex in lower Manhattan. A spokesman for the Manhattan District Attorney’s office declined to confirm the drive’s whereabouts, but people familiar with the office presume that it has been secured in a radio-frequency-isolation chamber in the Louis J. Lefkowitz State Office Building, on Centre Street. The chamber is protected by a double set of metal doors—the kind used in bank vaults—and its walls are lined with what looks like glimmering copper foil, to block remote attempts to tamper with digital evidence. It’s a modern equivalent of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

More here.

Looking at Cicely Tyson

Danielle A. Jackson at The Current:

“I see the beauty now,” my mother told me when I asked her what she thought of Cicely Tyson’s face, about a week after the pathbreaking actor died in January at ninety-six. “But I didn’t then.” By “then,” she meant the decade and a half in the middle of the twentieth century, when Tyson won role after role in well-financed productions in the Hollywood system and made-for-TV films broadcast on the networks. Those were the years people learned her name. In Tyson’s earliest roles—starting with 1956’s Carib Gold, in which she was part of an ensemble that included Diana Sands and Ethel Waters—she’d made uncredited appearances, customary for actors who were not yet in the union. Tyson was in her early thirties when she began acting, yet she’d place her age behind by a decade at her agent’s request. It was a plausible lie because Tyson kept a youthful glow, with taut, espresso-brown skin that had rosy undertones, round black eyes that pierced and trembled, an erudite poise that made it seem as though her reach stretched well beyond its diminutive frame. For events, she was wise and precise with her attire, a trait she attributed to her parents, who’d arrived at Ellis Island from Nevis toward the end of the 1910s and settled in an East Harlem tenement. “When she and my dad strode into [church]—Mom in her rayon frock, high heels, and straw hat cocked to one side—a hush fell over the sanctuary,” Tyson writes in her memoir, Just as I Am. This was beauty, with substance underneath—wielded as honor and armor.

“I see the beauty now,” my mother told me when I asked her what she thought of Cicely Tyson’s face, about a week after the pathbreaking actor died in January at ninety-six. “But I didn’t then.” By “then,” she meant the decade and a half in the middle of the twentieth century, when Tyson won role after role in well-financed productions in the Hollywood system and made-for-TV films broadcast on the networks. Those were the years people learned her name. In Tyson’s earliest roles—starting with 1956’s Carib Gold, in which she was part of an ensemble that included Diana Sands and Ethel Waters—she’d made uncredited appearances, customary for actors who were not yet in the union. Tyson was in her early thirties when she began acting, yet she’d place her age behind by a decade at her agent’s request. It was a plausible lie because Tyson kept a youthful glow, with taut, espresso-brown skin that had rosy undertones, round black eyes that pierced and trembled, an erudite poise that made it seem as though her reach stretched well beyond its diminutive frame. For events, she was wise and precise with her attire, a trait she attributed to her parents, who’d arrived at Ellis Island from Nevis toward the end of the 1910s and settled in an East Harlem tenement. “When she and my dad strode into [church]—Mom in her rayon frock, high heels, and straw hat cocked to one side—a hush fell over the sanctuary,” Tyson writes in her memoir, Just as I Am. This was beauty, with substance underneath—wielded as honor and armor.

more here.

East Side/ West Side (1963)

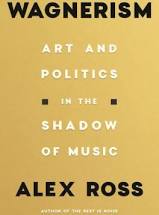

The Revolutionary Contradictions of Richard Wagner

Nathan Shields at The Baffler:

Mann contended that Wagner’s art was neither monolithically grand nor sinister but deeply, violently ambivalent. He cited Nietzsche’s swing from filial devotion to Oedipal rebellion as a case in point. In his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche hailed his friend’s art in terms that fused Wagner’s own revolutionary rhetoric with Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of self-annihilation: it broke the “spell of individuation,” reopening the way to “the innermost heart of things.” But over the following decade Nietzsche shifted slowly from acolyte to skeptic, estranged by Wagner’s growing nationalism, the spectacle of Bayreuth, and his own changing intellectual needs. The final breach, he wrote, was precipitated by the self-betrayal of Parsifal, in which “Wagner, seemingly the all-conquering, actually a decaying, despairing decadent, suddenly sank down helpless and shattered before the Christian cross.” Later, in The Case of Wagner (1888), Nietzsche concluded that there had been nothing there to betray in the first place. Wagner had always been a disease, a toxin, and a neurosis, even before the encounter with Schopenhauer. “Only the philosopher of decadence gave to the artist of decadence—himself.”

Mann contended that Wagner’s art was neither monolithically grand nor sinister but deeply, violently ambivalent. He cited Nietzsche’s swing from filial devotion to Oedipal rebellion as a case in point. In his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche hailed his friend’s art in terms that fused Wagner’s own revolutionary rhetoric with Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of self-annihilation: it broke the “spell of individuation,” reopening the way to “the innermost heart of things.” But over the following decade Nietzsche shifted slowly from acolyte to skeptic, estranged by Wagner’s growing nationalism, the spectacle of Bayreuth, and his own changing intellectual needs. The final breach, he wrote, was precipitated by the self-betrayal of Parsifal, in which “Wagner, seemingly the all-conquering, actually a decaying, despairing decadent, suddenly sank down helpless and shattered before the Christian cross.” Later, in The Case of Wagner (1888), Nietzsche concluded that there had been nothing there to betray in the first place. Wagner had always been a disease, a toxin, and a neurosis, even before the encounter with Schopenhauer. “Only the philosopher of decadence gave to the artist of decadence—himself.”

more here.

Friday Poem

For a real man not to dream to be a flower:

that we must see, is the cowardly thing.

……………………………. — Martha Nussbaum

I find in my notebook – “My desire is an Antony,”

and think, if it were, it would not be in my notebook,

so, consciousness is a dialogue with one’s self. Well,

who else a better listener? even when trapped in a

corner chair by the bad poet. I see that I’ve become

two again – bad poet, sullen listener – life the dialogue.

Let’s leave these two (See how we’ve become four?) and pay

attention to this multitudinous world as it swings

with its sisters about the sun, as the sun about the galaxy

that mote in the expanding universe. Yet, today’s

ticket will not carry us that far. We must get off or

the eternal conductor will catch us out. Let’s leave

the bad poet and the surly listener at La Cafe de Deux

Maggots drinking cheap red wine and arguing about

the existential moment. Let’s come back to Judith’s

garden where Iceland poppies open like mistresses

before the sun king. Let’s stand in the garden, still,

quiet, – all about us green fire.

Thursday, March 18, 2021

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “The Committed”

Aminatta Forna in The Guardian:

We were the unwanted, the unneeded and the unseen, invisible to all but ourselves.” And with those words he is back, the “man of two faces and two minds” as well as many guises: Vietnamese, French, American, soldier, academic, Japanese tourist, waiter, hoodlum, killer, communist, capitalist, spy. In 2016 the unnamed protagonist of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s first novel The Sympathizer won his creator a Pulitzer prize for fiction. In a distinctive voice, one that mixed erudition with the vernacular, quiet reflection with emotional outburst and came threaded with a biting wit, he recounted his life as a Viet Cong spy. His journey led him from a shack in Saigon to life among wealthy Vietnamese exiles in Los Angeles, finally to confront his own past years later back in Vietnam. There he is held in a re-education camp where he is interrogated and tortured by “the faceless man”, forced to write and rewrite his “confession” in an attempt to correct his ideological position: the result is the book itself.

We were the unwanted, the unneeded and the unseen, invisible to all but ourselves.” And with those words he is back, the “man of two faces and two minds” as well as many guises: Vietnamese, French, American, soldier, academic, Japanese tourist, waiter, hoodlum, killer, communist, capitalist, spy. In 2016 the unnamed protagonist of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s first novel The Sympathizer won his creator a Pulitzer prize for fiction. In a distinctive voice, one that mixed erudition with the vernacular, quiet reflection with emotional outburst and came threaded with a biting wit, he recounted his life as a Viet Cong spy. His journey led him from a shack in Saigon to life among wealthy Vietnamese exiles in Los Angeles, finally to confront his own past years later back in Vietnam. There he is held in a re-education camp where he is interrogated and tortured by “the faceless man”, forced to write and rewrite his “confession” in an attempt to correct his ideological position: the result is the book itself.

For decades the master narrative of the Vietnam war has been created by American books and movies. It is the story of the impact that fighting the war had on the bodies, minds and hearts of mainly white American males. It is, as Nguyen himself has observed in the past, the first time history has ever been written by the loser.

More here.

The Elusive Dream of Self-Driving Cars

M.R. O’Connor in Undark:

Deep in the Mojave Desert, 60 miles from the city of Barstow, is the Slash X Ranch Cafe, a former ranch where dirt bike riders and ATV adventurers can drink beer and eat burgers with fellow daredevils speeding across the desert. Displayed on a wall alongside trucker caps and taxidermy is a plaque that memorializes the 2004 DARPA Grand Challenge, a 142-mile race whose starting point was at Slash X Ranch Cafe.

Deep in the Mojave Desert, 60 miles from the city of Barstow, is the Slash X Ranch Cafe, a former ranch where dirt bike riders and ATV adventurers can drink beer and eat burgers with fellow daredevils speeding across the desert. Displayed on a wall alongside trucker caps and taxidermy is a plaque that memorializes the 2004 DARPA Grand Challenge, a 142-mile race whose starting point was at Slash X Ranch Cafe.

It was the first race in the world without human drivers. Instead, it featured the fever-dream inventions — robotic motorcycles, monster Humvees — of a handful of software engineers who were hellbent on creating fully autonomous vehicles and winning the million-dollar prize offered by the Defense Department’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

In “Driven: The Race to Create the Autonomous Car,” journalist Alex Davies mines court documents and interviews the original participants of the DARPA race to chronicle the heady early days of autonomous vehicle technology and its subsequent evolution into a billion-dollar race between corporate behemoths like Google, Uber, and Detroit automakers to be the first to put autonomous vehicles on the nation’s roads.

More here.

Daniel Dennett speaks to Robert Kuhn about Free Will

Encountering Thomas Sowell

Thomas Chatterton Williams in Law & Liberty:

The first time I heard the name Thomas Sowell was during that bitterly partisan—though in retrospect, comparatively tame—transition period from George W. Bush to Barack Obama. My mother’s younger sister, a gun-owning, born-again evangelical Christian and staunchly Republican voter from Southern California had by then become an active and vocal Facebook user. In those days, I was half a decade out of undergrad, living in New York City, making my first forays into the world of professional opinion-having. I felt my first (and, it would turn out, my last) stirrings of political romanticism in my exuberance over the candidacy and election of the first black president. Suffice it to say we locked digital horns on a regular basis. “It’s not about color for me,” my aunt said while railing against Obama. “For example, I love Thomas Sowell.”

The first time I heard the name Thomas Sowell was during that bitterly partisan—though in retrospect, comparatively tame—transition period from George W. Bush to Barack Obama. My mother’s younger sister, a gun-owning, born-again evangelical Christian and staunchly Republican voter from Southern California had by then become an active and vocal Facebook user. In those days, I was half a decade out of undergrad, living in New York City, making my first forays into the world of professional opinion-having. I felt my first (and, it would turn out, my last) stirrings of political romanticism in my exuberance over the candidacy and election of the first black president. Suffice it to say we locked digital horns on a regular basis. “It’s not about color for me,” my aunt said while railing against Obama. “For example, I love Thomas Sowell.”

To that side of my extended family, I became the stereotype of a coastal liberal, writing for the New York Times and wholly out of touch with the real America. In fact, I’ve always prided and defined myself as an anti-tribal thinker, and sometime contrarian, working firmly within a left-of-center black tradition—a tradition populated by brave and brilliant minds from Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray to Harold Cruse, Stanley Crouch, Orlando Patterson, at times even Zadie Smith and James Baldwin.

To that side of my extended family, I became the stereotype of a coastal liberal, writing for the New York Times and wholly out of touch with the real America. In fact, I’ve always prided and defined myself as an anti-tribal thinker, and sometime contrarian, working firmly within a left-of-center black tradition—a tradition populated by brave and brilliant minds from Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray to Harold Cruse, Stanley Crouch, Orlando Patterson, at times even Zadie Smith and James Baldwin.

More here.

Paul Feyerabend and Herbert Feigl (1962)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axqNkID_ibA