Elise Archias at Artforum:

JOAN MITCHELL’S PAINTINGS from the late 1950s have space in them. They are big surfaces covered with marks, like most Abstract Expressionist paintings made in New York in the same decade, and so they look much flatter than a carefully measured perspectival scene from the 1940s by, for example, Edward Hopper. But compared with almost everything her most productive and now famous peers were doing at the same time, Mitchell’s paintings are practically voluminous.

JOAN MITCHELL’S PAINTINGS from the late 1950s have space in them. They are big surfaces covered with marks, like most Abstract Expressionist paintings made in New York in the same decade, and so they look much flatter than a carefully measured perspectival scene from the 1940s by, for example, Edward Hopper. But compared with almost everything her most productive and now famous peers were doing at the same time, Mitchell’s paintings are practically voluminous.

Consider her George Went Swimming at Barnes Hole, but It Got Too Cold, 1957, for example, alongside Helen Frankenthaler’s Round Trip, 1957. Both pictures invite us to reflect on their dialogue with the landscape-painting tradition, Frankenthaler’s via green triangular “mountains” and a blue “lake” in the foreground, Mitchell’s with the suggestion of a horizon line in the upper right corner and the titular swimming hole. Round Trip showcases a variety of painterly techniques. It is as if Frankenthaler chose each one for its capacity to oppose one of the others: dripping counters drawing; staining denies outlining; Lascaux-like ochre smudges must make room for academic cliché.

more here.

“EVERYBODY BEHAVES BADLY,” says Hemingway’s Jake Barnes. “Give them the proper chance.” Why read novels about people behaving badly? Can a novel about bad people do readers good? These questions about the real-world effects of fictional characters — not just their “reality effects” — have come to the fore in recent years with the ascendancy of autofiction, on the one hand, and the persistence of the stoutly character-driven novel, on the other: the kind where characters, and, by extension, readers, get to know, and accept, social others who are nothing like them. Whereas autofiction asserts a kind of apolitical license — it’s my life, so it doesn’t matter if my problems seem trivial and if everyone I know is exactly like me — it’s incumbent on the latter kind of novelist to make social difference legible, rather than erasing or tokenizing it. It’s a tall order, and between the demands of professional and lay critics, on and off Twitter, the bar for ethical fiction, in which characterization is the vehicle for moral instruction, keeps getting raised ever higher.

“EVERYBODY BEHAVES BADLY,” says Hemingway’s Jake Barnes. “Give them the proper chance.” Why read novels about people behaving badly? Can a novel about bad people do readers good? These questions about the real-world effects of fictional characters — not just their “reality effects” — have come to the fore in recent years with the ascendancy of autofiction, on the one hand, and the persistence of the stoutly character-driven novel, on the other: the kind where characters, and, by extension, readers, get to know, and accept, social others who are nothing like them. Whereas autofiction asserts a kind of apolitical license — it’s my life, so it doesn’t matter if my problems seem trivial and if everyone I know is exactly like me — it’s incumbent on the latter kind of novelist to make social difference legible, rather than erasing or tokenizing it. It’s a tall order, and between the demands of professional and lay critics, on and off Twitter, the bar for ethical fiction, in which characterization is the vehicle for moral instruction, keeps getting raised ever higher. Months of lockdowns and waves of surging Covid cases throughout last year shuttered clinics and testing labs, or reduced hours at other places, resulting in steep declines in the number of screenings, including for breast and colorectal cancers, experts have said. Numerous studies showed that the number of patients screened or given a diagnosis of cancer fell during the early months of the pandemic. By mid-June, the rate of screenings for breast, colon and cervical cancers were still 29 percent to 36 percent lower than their prepandemic levels, according to

Months of lockdowns and waves of surging Covid cases throughout last year shuttered clinics and testing labs, or reduced hours at other places, resulting in steep declines in the number of screenings, including for breast and colorectal cancers, experts have said. Numerous studies showed that the number of patients screened or given a diagnosis of cancer fell during the early months of the pandemic. By mid-June, the rate of screenings for breast, colon and cervical cancers were still 29 percent to 36 percent lower than their prepandemic levels, according to  Scientists have made fabrics from polythene in a move they say could reduce plastic pollution and make the fashion industry more sustainable. Polythene is a ubiquitous plastic, found in everything from plastic bags to food packaging. The new textiles have potential uses in sports wear, and even high-end fashion, according to US researchers. The plastic “cloth” is more environmentally-friendly than natural fibres, and can be recycled, they say. Dr Svetlana Boriskina, from the department of engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, US, said plastic bags that nobody wants can be turned into high-performance fabrics with a low environmental footprint. “There’s no reason why the simple plastic bag cannot be made into fibre and used as a high-end garment,” she told BBC News. “You can go literally from trash to a high-performance garment that provides comfort and can be recycled multiple times back into a new garment.”

Scientists have made fabrics from polythene in a move they say could reduce plastic pollution and make the fashion industry more sustainable. Polythene is a ubiquitous plastic, found in everything from plastic bags to food packaging. The new textiles have potential uses in sports wear, and even high-end fashion, according to US researchers. The plastic “cloth” is more environmentally-friendly than natural fibres, and can be recycled, they say. Dr Svetlana Boriskina, from the department of engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, US, said plastic bags that nobody wants can be turned into high-performance fabrics with a low environmental footprint. “There’s no reason why the simple plastic bag cannot be made into fibre and used as a high-end garment,” she told BBC News. “You can go literally from trash to a high-performance garment that provides comfort and can be recycled multiple times back into a new garment.” In the summer of 1973 Time magazine decided not to run a piece that it had commissioned,

In the summer of 1973 Time magazine decided not to run a piece that it had commissioned,  When Avi Wigderson and László Lovász began their careers in the 1970s, theoretical computer science and pure mathematics were almost entirely separate disciplines. Today, they’ve grown so close it’s hard to find the line between them. For their many fundamental contributions to both fields, and for their work drawing them together, today Lovász and Wigderson were awarded the

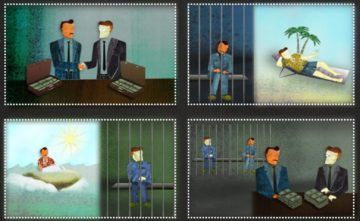

When Avi Wigderson and László Lovász began their careers in the 1970s, theoretical computer science and pure mathematics were almost entirely separate disciplines. Today, they’ve grown so close it’s hard to find the line between them. For their many fundamental contributions to both fields, and for their work drawing them together, today Lovász and Wigderson were awarded the  When and why do people cooperate or compete? Researchers at the RAND Corporation studied this question in the 1950s using what was then a new decision science called game theory. Game theory was developed during World War II by the Hungarian mathematical physicist and leading Manhattan Project contributor John von Neumann and the Austrian economist Oskar Morgenstern. It was immediately used by operations researchers for military logistics, and to develop a science of military decision making. By the late 1950s it was applied to nuclear deterrence, with the future Nobel laureate economist Thomas Schelling publishing The Strategy of Conflict in 1960.

When and why do people cooperate or compete? Researchers at the RAND Corporation studied this question in the 1950s using what was then a new decision science called game theory. Game theory was developed during World War II by the Hungarian mathematical physicist and leading Manhattan Project contributor John von Neumann and the Austrian economist Oskar Morgenstern. It was immediately used by operations researchers for military logistics, and to develop a science of military decision making. By the late 1950s it was applied to nuclear deterrence, with the future Nobel laureate economist Thomas Schelling publishing The Strategy of Conflict in 1960. In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience last week, University of Pittsburgh researchers described how reward signals in the brain are modulated by uncertainty. Dopamine signals are intertwined with reward learning; they teach the brain which cues or actions predict the best rewards. New findings from the Stauffer lab at Pitt School of Medicine indicate that dopamine signals also reflect the certainty surrounding reward predictions. In short, dopamine signals might teach the brain about the likelihood of getting a reward.

In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience last week, University of Pittsburgh researchers described how reward signals in the brain are modulated by uncertainty. Dopamine signals are intertwined with reward learning; they teach the brain which cues or actions predict the best rewards. New findings from the Stauffer lab at Pitt School of Medicine indicate that dopamine signals also reflect the certainty surrounding reward predictions. In short, dopamine signals might teach the brain about the likelihood of getting a reward. David Wyatt has worked in public relations for more than 20 years, having worked his way up to become a senior vice-president at an Austin, Texas-based firm. He recognises his privileges as a

David Wyatt has worked in public relations for more than 20 years, having worked his way up to become a senior vice-president at an Austin, Texas-based firm. He recognises his privileges as a  Mississippi John Hurt, Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Tina Turner, Bob Dylan, and Beck are among the hundreds who have sung a version of Stagolee’s story. Lloyd Price took a rollicking rendition of “Stagger Lee” to the top of the pop charts in 1959. Such brushes with mainstream success never compromised Stag’s street cred, though. In bars, barbershops, and prisons, he remained “the baddest n—– who ever lived,” the antihero of profane epics and rhyming “toasts” whose exploits offered a fantasy of freedom from life’s indignities. Stagolee haunts the prose of Richard Wright and Toni Morrison; James Baldwin worked on a novel about the character and late in his life published a long poem called “Staggerlee Wonders.”

Mississippi John Hurt, Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Tina Turner, Bob Dylan, and Beck are among the hundreds who have sung a version of Stagolee’s story. Lloyd Price took a rollicking rendition of “Stagger Lee” to the top of the pop charts in 1959. Such brushes with mainstream success never compromised Stag’s street cred, though. In bars, barbershops, and prisons, he remained “the baddest n—– who ever lived,” the antihero of profane epics and rhyming “toasts” whose exploits offered a fantasy of freedom from life’s indignities. Stagolee haunts the prose of Richard Wright and Toni Morrison; James Baldwin worked on a novel about the character and late in his life published a long poem called “Staggerlee Wonders.” In 1843, the Independent Order of Odd Fellowship was established in Baltimore following a wave of reforms within the Grand Lodge of Odd Fellows of the United States. In the years since the Odd Fellows first arrived from England in 1819, the fraternal organization had gained a reputation for boisterous carousing while garnering membership as a working-class alternative to Freemasonry. The Antimasonic movement of the 1830s introduced a massive wave of upper-middle-class initiates to the Odd Fellows, who brought with them a new emphasis on moral uprightness. Initiation fees increased, a newly formed judicial system expelled disreputable members, and alcohol was banned from all lodges, which began to save and invest their funds, no longer assisting members in times of need. In this new spirit of exclusivity and high principles, the I.O.O.F. instituted a body of rituals to accompany a streamlined and regulated order of degrees. The keys to these rituals were a set of books owned by each Grand Lodge, the “Albums of Written and Unwritten Work.”

In 1843, the Independent Order of Odd Fellowship was established in Baltimore following a wave of reforms within the Grand Lodge of Odd Fellows of the United States. In the years since the Odd Fellows first arrived from England in 1819, the fraternal organization had gained a reputation for boisterous carousing while garnering membership as a working-class alternative to Freemasonry. The Antimasonic movement of the 1830s introduced a massive wave of upper-middle-class initiates to the Odd Fellows, who brought with them a new emphasis on moral uprightness. Initiation fees increased, a newly formed judicial system expelled disreputable members, and alcohol was banned from all lodges, which began to save and invest their funds, no longer assisting members in times of need. In this new spirit of exclusivity and high principles, the I.O.O.F. instituted a body of rituals to accompany a streamlined and regulated order of degrees. The keys to these rituals were a set of books owned by each Grand Lodge, the “Albums of Written and Unwritten Work.” Four billion years ago, Earth was a lifeless place. Nothing struggled, thought, or wanted. Slowly, that changed. Seawater leached chemicals from rocks; near thermal vents, those chemicals jostled and combined. Some hit upon the trick of making copies of themselves that, in turn, made more copies. The replicating chains were caught in oily bubbles, which protected them and made replication easier; eventually, they began to venture out into the open sea. A new level of order had been achieved on Earth. Life had begun.

Four billion years ago, Earth was a lifeless place. Nothing struggled, thought, or wanted. Slowly, that changed. Seawater leached chemicals from rocks; near thermal vents, those chemicals jostled and combined. Some hit upon the trick of making copies of themselves that, in turn, made more copies. The replicating chains were caught in oily bubbles, which protected them and made replication easier; eventually, they began to venture out into the open sea. A new level of order had been achieved on Earth. Life had begun. You might think that human beings, exhausted by competing for resources and rewards in the real world, would take it easy and stick to cooperation in their spare time. But no; we are fascinated by competition, and invent games and sports to create artificial competition just for fun. These competitions turn out to be wonderful laboratories for exploring concepts like optimization, resource allocation, strategy, and human psychology. Today’s guest, Daryl Morey, is a world leader in thinking analytically about sports, as well as the relationship between impersonal data and the vagaries of human behavior. He’s currently an executive in charge of the Philadelphia 76ers, but I promise you don’t need to be a fan of the Sixers or of basketball or of sports in general to enjoy this wide-ranging conversation.

You might think that human beings, exhausted by competing for resources and rewards in the real world, would take it easy and stick to cooperation in their spare time. But no; we are fascinated by competition, and invent games and sports to create artificial competition just for fun. These competitions turn out to be wonderful laboratories for exploring concepts like optimization, resource allocation, strategy, and human psychology. Today’s guest, Daryl Morey, is a world leader in thinking analytically about sports, as well as the relationship between impersonal data and the vagaries of human behavior. He’s currently an executive in charge of the Philadelphia 76ers, but I promise you don’t need to be a fan of the Sixers or of basketball or of sports in general to enjoy this wide-ranging conversation. Today, many people see democracy as under threat in a way that only a decade ago seemed unimaginable. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, it seemed like democracy was the way of the future. But nowadays, the state of democracy looks very different; we

Today, many people see democracy as under threat in a way that only a decade ago seemed unimaginable. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, it seemed like democracy was the way of the future. But nowadays, the state of democracy looks very different; we