Heller McAlpin in The Christian Science Monitor:

“These Precious Days,” Ann Patchett’s generous new collection of essays, nearly all of which were previously published in periodicals, offers a burst of warm positivity. Like her first collection, “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (2013), this appealing mix of the personal and the professional highlights the centrality of books, family, friendship, and compassion in Patchett’s life. At the heart of “These Precious Days” is the title essay, a tribute to a woman Patchett befriended in what turned out to be the last years of the woman’s life. Patchett, who memorialized her difficult, intense friendship with fellow writer Lucy Grealy in “Truth & Beauty” (2004), has an easier time celebrating her less complicated, serendipitous relationship with Sooki Raphael, Tom Hanks’ longtime personal assistant.

“These Precious Days,” Ann Patchett’s generous new collection of essays, nearly all of which were previously published in periodicals, offers a burst of warm positivity. Like her first collection, “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (2013), this appealing mix of the personal and the professional highlights the centrality of books, family, friendship, and compassion in Patchett’s life. At the heart of “These Precious Days” is the title essay, a tribute to a woman Patchett befriended in what turned out to be the last years of the woman’s life. Patchett, who memorialized her difficult, intense friendship with fellow writer Lucy Grealy in “Truth & Beauty” (2004), has an easier time celebrating her less complicated, serendipitous relationship with Sooki Raphael, Tom Hanks’ longtime personal assistant.

Patchett’s essays often carry life lessons. What she learns from Sooki is to remember to treasure and pay attention to every precious moment. Another lesson here is about the deep gratification of extending oneself. That’s what Patchett did when she opened her Nashville home to Sooki so her new friend could participate in a medical trial not then available in her home state of California. Patchett, a born nurturer, writes that even though she barely knew Sooki at that point, “there have been few moments in my life when I have felt so certain: I was supposed to help.”

Sooki turns out to be an ideal houseguest – self-sufficient, tidy, quiet, thoughtful. When the pandemic hits, they go into lockdown together with Patchett’s husband, Karl VanDevender, a doctor who helped arrange for Sooki’s enrollment in the trial. Patchett spends her days writing or packing books to ship from her closed bookstore. Between treatments, Sooki finally gets to devote herself to her passion: painting. The two women practice yoga and cook vegetarian meals together. “Most of the writers and artists I know were made for sheltering in place,” Patchett writes. “The world asks us to engage, and for the most part we can, but given the choice, we’d rather stay home.”

More here.

In April of 2001 I began my monthly Skeptic column at Scientific American, the longest continuously published magazine in the country dating back to 1845. With Stephen Jay Gould as my role model (and subsequent friend), it was my dream to match his 300 consecutive columns that he achieved at Natural History magazine, which would have taken me to April, 2026. Alas, my streak ended in January of 2019 after a run of 214 essays.

In April of 2001 I began my monthly Skeptic column at Scientific American, the longest continuously published magazine in the country dating back to 1845. With Stephen Jay Gould as my role model (and subsequent friend), it was my dream to match his 300 consecutive columns that he achieved at Natural History magazine, which would have taken me to April, 2026. Alas, my streak ended in January of 2019 after a run of 214 essays.

The Invisible Dragon exemplifies Hickey’s sensibility. It mounts an argument that beauty still mattered at a time when it was viewed as being anathema to relevant art-making, and it does so elegantly and seemingly effortlessly. In one essay, he compares Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexually explicit photography of queer subcultures to Caravaggio’s religious paintings. Using language indebted to art theory of the postwar era, he muses on sleek Mapplethorpe pictures that had been the subject of a culture war in the early ’90s, writing that they “seem so obviously to have come from someplace else, down by the piers, and to have brought with them, into the world of ice-white walls, the aura of knowing smiles, bad habits, rough language, and smoky, crowded rooms with raw brick walls, sawhorse bars and hand-lettered signs on the wall. They may be legitimate, but like my second cousins, Tim and Duane, they are far from respectable, even now.” Such a statement came alongside an honest disclosure: he had first come across these works in a coke dealer’s penthouse.

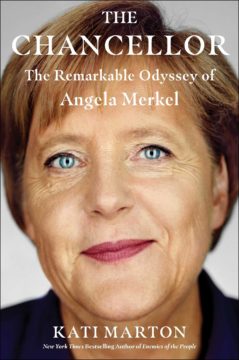

The Invisible Dragon exemplifies Hickey’s sensibility. It mounts an argument that beauty still mattered at a time when it was viewed as being anathema to relevant art-making, and it does so elegantly and seemingly effortlessly. In one essay, he compares Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexually explicit photography of queer subcultures to Caravaggio’s religious paintings. Using language indebted to art theory of the postwar era, he muses on sleek Mapplethorpe pictures that had been the subject of a culture war in the early ’90s, writing that they “seem so obviously to have come from someplace else, down by the piers, and to have brought with them, into the world of ice-white walls, the aura of knowing smiles, bad habits, rough language, and smoky, crowded rooms with raw brick walls, sawhorse bars and hand-lettered signs on the wall. They may be legitimate, but like my second cousins, Tim and Duane, they are far from respectable, even now.” Such a statement came alongside an honest disclosure: he had first come across these works in a coke dealer’s penthouse. For much of her sixteen years in office as Germany’s chancellor, Angela Dorothea Merkel, née Kasner, has been ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’, to quote Churchill’s famous dictum on the Soviet Union. Her meteoric rise defied all rational explanation. A woman from East Germany, a scientist with an inbuilt aversion to straddling the political stage and mounting the bully pulpit: how could she succeed in a country with a conservative mind-set which had all but closed out women from professional advancement?

For much of her sixteen years in office as Germany’s chancellor, Angela Dorothea Merkel, née Kasner, has been ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’, to quote Churchill’s famous dictum on the Soviet Union. Her meteoric rise defied all rational explanation. A woman from East Germany, a scientist with an inbuilt aversion to straddling the political stage and mounting the bully pulpit: how could she succeed in a country with a conservative mind-set which had all but closed out women from professional advancement? “These Precious Days,” Ann Patchett’s generous new collection of essays, nearly all of which were previously published in periodicals, offers a burst of warm positivity. Like her first collection, “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (2013), this appealing mix of the personal and the professional highlights the centrality of books, family, friendship, and compassion in Patchett’s life. At the heart of “These Precious Days” is the title essay, a tribute to a woman Patchett befriended in what turned out to be the last years of the woman’s life. Patchett, who memorialized her difficult, intense friendship with fellow writer Lucy Grealy in “Truth & Beauty” (2004), has an easier time celebrating her less complicated, serendipitous relationship with Sooki Raphael, Tom Hanks’ longtime personal assistant.

“These Precious Days,” Ann Patchett’s generous new collection of essays, nearly all of which were previously published in periodicals, offers a burst of warm positivity. Like her first collection, “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (2013), this appealing mix of the personal and the professional highlights the centrality of books, family, friendship, and compassion in Patchett’s life. At the heart of “These Precious Days” is the title essay, a tribute to a woman Patchett befriended in what turned out to be the last years of the woman’s life. Patchett, who memorialized her difficult, intense friendship with fellow writer Lucy Grealy in “Truth & Beauty” (2004), has an easier time celebrating her less complicated, serendipitous relationship with Sooki Raphael, Tom Hanks’ longtime personal assistant. There’s more recognition that ecological restoration can be an essential tool in fighting climate change, and there are many projects aimed at restoring degraded forests to capture carbon. Still, the focus on forests ignores much of the land in the tropics that would not naturally be forested. A team of scientists is arguing that people need to become aware of other habitats and their value.

There’s more recognition that ecological restoration can be an essential tool in fighting climate change, and there are many projects aimed at restoring degraded forests to capture carbon. Still, the focus on forests ignores much of the land in the tropics that would not naturally be forested. A team of scientists is arguing that people need to become aware of other habitats and their value.

The pandemic has unveiled the reality behind what’s been vexing the academic humanities for decades. Classes went online, as business demanded. Classes returned to in-person, as business demanded. Since humanities enrollments have been declining, naturally higher education has been hiring more administrators to hire consultants to figure out how to attract what we’ve grown used to calling its customer base—or, if that doesn’t pan out, to provide a rationale for cutting its programs. When students and administrators aren’t teaming up against professors for not delivering what the customer wants, all parties seem to have made a non-aggression pact for reasons that have almost nothing to do with liberal education.

The pandemic has unveiled the reality behind what’s been vexing the academic humanities for decades. Classes went online, as business demanded. Classes returned to in-person, as business demanded. Since humanities enrollments have been declining, naturally higher education has been hiring more administrators to hire consultants to figure out how to attract what we’ve grown used to calling its customer base—or, if that doesn’t pan out, to provide a rationale for cutting its programs. When students and administrators aren’t teaming up against professors for not delivering what the customer wants, all parties seem to have made a non-aggression pact for reasons that have almost nothing to do with liberal education. Feynman: There was a sister. There was a brother that came after approximately three years. Or maybe I was five, four, six, three, I don’t remember. But that brother died, after a relatively short time, like a month or so. I can still remember that, so I can’t have been too young, because I can remember especially that the brother had a finger bleeding all the time. That’s what happened — it was some kind of disease that didn’t heal. And also, asking the nurse how they knew whether it was a boy or a girl, and being taught: it’s by the shape of the ear — and thinking that that’s rather strange. There’s so much difference in the world between men and women that they should bother to make any difference, a boy from a girl, with just the shape of the ear! It didn’t sound like a sensible thing. Now, I remember that I had another, a sister, when I was nine years old, so it’s possible that I’m remembering my question at the age of nine or ten, and not at the age of the other child, because it sounds incredible to me now that I would have had such a deep thought about society at the earlier age. I don’t know. I can’t tell you what age I was, but I remember that, because it was an interesting answer. I couldn’t understand it really. They make such a fuss — everybody dresses differently; they go to so much trouble, their hair different — just because the ear shape is different? What sort of an answer is that?

Feynman: There was a sister. There was a brother that came after approximately three years. Or maybe I was five, four, six, three, I don’t remember. But that brother died, after a relatively short time, like a month or so. I can still remember that, so I can’t have been too young, because I can remember especially that the brother had a finger bleeding all the time. That’s what happened — it was some kind of disease that didn’t heal. And also, asking the nurse how they knew whether it was a boy or a girl, and being taught: it’s by the shape of the ear — and thinking that that’s rather strange. There’s so much difference in the world between men and women that they should bother to make any difference, a boy from a girl, with just the shape of the ear! It didn’t sound like a sensible thing. Now, I remember that I had another, a sister, when I was nine years old, so it’s possible that I’m remembering my question at the age of nine or ten, and not at the age of the other child, because it sounds incredible to me now that I would have had such a deep thought about society at the earlier age. I don’t know. I can’t tell you what age I was, but I remember that, because it was an interesting answer. I couldn’t understand it really. They make such a fuss — everybody dresses differently; they go to so much trouble, their hair different — just because the ear shape is different? What sort of an answer is that? Many people have told me that they cannot cook to save their lives. I don’t believe them. A lot of them can build a dresser out of an IKEA box – despite the fact that the instructions read like they were written by a wall-eyed robot whose first language was Esperanto, while writing code in C++ or programming a television set to switch between the news and a soccer match. How could it be possible that they are not able to follow a simple set of instructions?

Many people have told me that they cannot cook to save their lives. I don’t believe them. A lot of them can build a dresser out of an IKEA box – despite the fact that the instructions read like they were written by a wall-eyed robot whose first language was Esperanto, while writing code in C++ or programming a television set to switch between the news and a soccer match. How could it be possible that they are not able to follow a simple set of instructions? Before she married her husband, Kiersten Little considered him ideal father material. “We were always under the mentality of, ‘Oh yeah, when you get married, you have kids,” she said. “It was this expected thing.” Expected, that is, until the couple took an eight-month road trip after Ms. Little got her master’s degree in public health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, N.C. “When we were out west — California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho — we were driving through areas where the whole forest was dead, trees knocked over,” Ms. Little said. “We went through southern Louisiana, which was hit by two hurricanes last year, and whole towns were leveled, with massive trees pulled up by their roots.” Now 30 and two years into her marriage, Ms. Little feels “the burden of knowledge,” she said. The couple sees mounting disaster when reading the latest

Before she married her husband, Kiersten Little considered him ideal father material. “We were always under the mentality of, ‘Oh yeah, when you get married, you have kids,” she said. “It was this expected thing.” Expected, that is, until the couple took an eight-month road trip after Ms. Little got her master’s degree in public health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, N.C. “When we were out west — California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho — we were driving through areas where the whole forest was dead, trees knocked over,” Ms. Little said. “We went through southern Louisiana, which was hit by two hurricanes last year, and whole towns were leveled, with massive trees pulled up by their roots.” Now 30 and two years into her marriage, Ms. Little feels “the burden of knowledge,” she said. The couple sees mounting disaster when reading the latest  Like many of the great perfumers, Jean Carles was a son of Grasse, a country town in the hills north of Cannes, on the French Riviera. Grasse, once a state unto itself, sits in a natural amphitheater of south-facing limestone cliffs, at the head of a valley of meadows sloping gently to the sea. The combined effect of this geography and the dulcet Mediterranean climate is a harvest of roses, jasmine, and bitter-orange blossoms that is exceptionally fragrant, and for hundreds of years the town has been known as the capital of the perfume trade. When Carles began his training, early in the twentieth century, a priesthood of Grassois perfumers presided over the industry. These so-called nez, or noses, were regarded with an awe of the sort that attaches, perhaps especially in France, to artistic genius. They were vessels of divine talent, their creations as wondrously perfect as the flowers of Grasse.

Like many of the great perfumers, Jean Carles was a son of Grasse, a country town in the hills north of Cannes, on the French Riviera. Grasse, once a state unto itself, sits in a natural amphitheater of south-facing limestone cliffs, at the head of a valley of meadows sloping gently to the sea. The combined effect of this geography and the dulcet Mediterranean climate is a harvest of roses, jasmine, and bitter-orange blossoms that is exceptionally fragrant, and for hundreds of years the town has been known as the capital of the perfume trade. When Carles began his training, early in the twentieth century, a priesthood of Grassois perfumers presided over the industry. These so-called nez, or noses, were regarded with an awe of the sort that attaches, perhaps especially in France, to artistic genius. They were vessels of divine talent, their creations as wondrously perfect as the flowers of Grasse.