Bob Blaisdell in The Christian Science Monitor:

Readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous prose and poetry might be unaware of how often he wrote about science. As John Tresch explains in “The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science,” in the late 1840s, near the end of his life, Poe had established for himself “a unique position as fiction writer, poet, critic, and expert on scientific matters – crossing paths with and learning from those who were producing the ‘apparent miracles’ of modern science.”

Readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous prose and poetry might be unaware of how often he wrote about science. As John Tresch explains in “The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science,” in the late 1840s, near the end of his life, Poe had established for himself “a unique position as fiction writer, poet, critic, and expert on scientific matters – crossing paths with and learning from those who were producing the ‘apparent miracles’ of modern science.”

Poe exposed pseudoscientific hoaxes – and then, to get his own writing noticed, created them himself. He finally received critical acclaim for his now-classic short stories, among them “The Tell-Tale Heart” (which Tresch describes as “an act of violent irrationality [detailed] in the language of scientific method”) and “The Raven” (which Poe himself proclaimed “the greatest poem that ever was written”).

Tresch has painted a full landscape of the journalism of the time, describing the conflicts between writers who made serious scientific observations and those eager to sensationalize or misrepresent new discoveries. “Poe saw his age’s many humbugs and its ‘men of science’ pushing for foolproof forms of scientific authority as secret partners,” writes Tresch. “Together they were establishing the modern matrix of entertainment and science, doubt and certainty. Those who successfully denounced the tricks of charlatans were precisely those with the skills to make themselves believed.”

More here.

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World: Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar: Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook:

Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook: “Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground.

“Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground. W

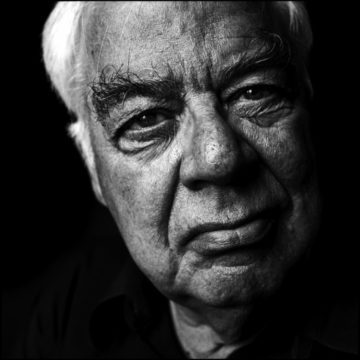

W Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said.

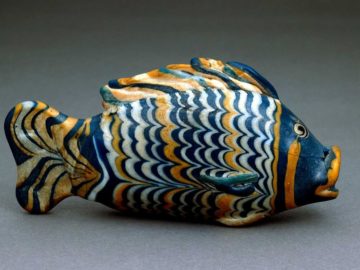

Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said. Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent.

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent. In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister

In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister  I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after

I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after  Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper.

Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper. Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy.

Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy. Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born.

Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born.