Category: Recommended Reading

On Albert Camus’s Legendary Postwar Speech at Columbia University

Robert Meagher in Literary Hub:

On Thursday evening, March 28, every seat and open space in Columbia University’s McMillin Theater was taken. Those who still stood in line and hoped for entry were out of luck. The scene was without precedent. No lecture delivered in French at Columbia had ever drawn more than two or three hundred listeners, and yet four or five times that many had come to hear Albert Camus read his prepared remarks entitled “La Crise de l’Homme” (“The Human Crisis”). What they heard was not the cultural excursion they had come for. Instead, it was arguably the most prophetic and unsettling speech Camus ever gave.

On Thursday evening, March 28, every seat and open space in Columbia University’s McMillin Theater was taken. Those who still stood in line and hoped for entry were out of luck. The scene was without precedent. No lecture delivered in French at Columbia had ever drawn more than two or three hundred listeners, and yet four or five times that many had come to hear Albert Camus read his prepared remarks entitled “La Crise de l’Homme” (“The Human Crisis”). What they heard was not the cultural excursion they had come for. Instead, it was arguably the most prophetic and unsettling speech Camus ever gave.

On that night, in less than thirty minutes, he somehow managed to distill and convey his deepest fears and steepest challenges in words that have lost none of their urgency or relevance in the 75 years since he spoke them. Before we move on to what he had to say that evening, the chosen title of his brief talk calls for careful scrutiny.

More here.

Why Do Wes Anderson Movies Look Like That?

Hogarth the European?

The title of Tate Britain’s latest exhibition, “Hogarth and Europe,” is slightly misleading. Setting out, as it does, to “suggest the cross currents, parallels and sympathies that crossed borders” during William Hogarth’s time, it more effectively makes clear some obvious cultural differences. Hogarth is celebrated for his social satires of eighteenth-century life but each time he is compared with a European contemporary—the curators have placed his works beside pieces from Amsterdam, Paris, Venice, and beyond—Hogarth only appears more bawdy, more biting, and more British.

Take, for example, the group of Venetian painters. Pietro Longhi may have elicited comparisons to Hogarth for his genre scenes, but The Painter in His Studio (ca. 1741–44), in which an artist paints an aristocratic young woman seated in his studio, feels like a straightforward portrayal of fashionable society and lacks the narrative vitality of Hogarth’s The Distressed Poet (1733–35).

more here.

On ‘Sybil & Cyril: Cutting Through Time’ By Jenny Uglow

Norma Clarke at Literary Review:

Few historians write better about pictures than Uglow, and her commentaries make you look and look again at bright colour plates that deliver little shocks. Physically, linocuts are not large: the whirligig of Cyril’s The Merry-go-round and the glorious swirl of ’Appy ’Ampstead burst from confined spaces; The Eight and Bringing in the Boat are not much bigger than a sheet of A4. The technical ability required to succeed in this medium is immense. The same could be said for piecing together the lives of individuals who covered their tracks and told themselves stories that were only partially true. Enough scraps survive to suggest that Cyril loved Sybil and was sad to lose her (he went back to his ‘quiet’ and kindly, amenable wife, and nothing was said in the family about his twenty-year absence). Sybil, who settled happily on Vancouver Island and whose reputation grew as she continued to work, was always busy, if not sketching and painting and linocutting then teaching, making her own clothes and boiling prodigious quantities of jam. To her brisk denial that her domestic relationship with her artist-collaborator had been that of lover, Uglow responds, ‘and who can deny her the right to possess the facts of her own life?’

Few historians write better about pictures than Uglow, and her commentaries make you look and look again at bright colour plates that deliver little shocks. Physically, linocuts are not large: the whirligig of Cyril’s The Merry-go-round and the glorious swirl of ’Appy ’Ampstead burst from confined spaces; The Eight and Bringing in the Boat are not much bigger than a sheet of A4. The technical ability required to succeed in this medium is immense. The same could be said for piecing together the lives of individuals who covered their tracks and told themselves stories that were only partially true. Enough scraps survive to suggest that Cyril loved Sybil and was sad to lose her (he went back to his ‘quiet’ and kindly, amenable wife, and nothing was said in the family about his twenty-year absence). Sybil, who settled happily on Vancouver Island and whose reputation grew as she continued to work, was always busy, if not sketching and painting and linocutting then teaching, making her own clothes and boiling prodigious quantities of jam. To her brisk denial that her domestic relationship with her artist-collaborator had been that of lover, Uglow responds, ‘and who can deny her the right to possess the facts of her own life?’

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Geese

That day the sun rose as if

it was the most natural thing

in the world; as if the long lake

glaciers had dug in the hard

bed of a withered sea

would keep the sea’s salt

buried forever like treasure;

as if the least you could expect

was for geese to swim through

blue air in a luminous shoal,

a great white mesh hauled

from the deep blue of the lake;

as if snow itself had hatched

a flock of fat flakes on the ground

and taught them how to fly

under their own steam; or as if

it should come as no surprise

to find yourself amazed,

between the salt and the sunlight,

catching snow-geese with your bare eyes.

by Robert Travers

from The Yale Review

Wounded Women: The feminism of vulnerability

Jessa Crispin in Boston Review:

Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another.

Last May, after the Isla Vista shooter’s manifesto revealed a deep misogyny, women went online to talk about the violent retaliation of men they had rejected, to describe the feeling of being intimidated or harassed. These personal experiences soon took on a sense of universality. And so #yesallwomen was born—yes all women have been victims of male violence in one form or another.

I was bothered by the hashtag campaign. Not by the male response, which ranged from outraged and cynical to condescending, nor the way the media dove in because the campaign was useful fodder. I recoiled from the gendering of pain, the installation of victimhood into the definition of femininity—and from the way pain became a polemic.

The campaign extended beyond Twitter. At online magazines such as Impose, The Hairpin, and The Toast, writers from Emma Aylor to Roxane Gay told similar stories in 2,500 words rather than 140 characters. Suddenly women writers were being valued for their stories of surviving violence and trauma. Bestsellers such as Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams portrayed women as inherently vulnerable. The New York Times Book Review recently proclaimed “a moment” for the female personal essayist.

No longer are the news or male commentators telling women they are at risk in the big, bad world, a decades-old manipulative ploy to keep us “safe” at home where we belong. Women are repeating this story for a different effect: women are a breed apart—unified in our experience and responses, distinct from those of men.

This emotional segregation is not good for us. I am worried about the implications of throwing the label “women’s pain” around individual experiences of suffering, and I am even more uncomfortable with women who feel free to speak for all women. I worry about making pain a ticket to gain entry into the women’s club. And I worry that the assumption of vulnerability threatens to invigorate just the sexist evils it aims to combat by demanding that men serve as shields against it.

More here.

Did Cars Rescue Our Cities From Horses?

Brandon Kiem in Nautilus:

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

For a recent telling, you can turn to SuperFreakonomics, the best-selling 2009 book by economist Steven D. Levitt and journalist Stephen J. Dubner. The authors describe how, in the late 19th century, the streets of fast-industrializing cities were congested with horses, each pulling a cart or a coach, one after the other, in some places three abreast. There were something like 200,000 horses in New York City alone, depositing manure at a rate of roughly 35 pounds per day, per horse. It piled high in vacant lots and “lined city streets like banks of snow.” The elegant brownstone stoops so beloved of contemporary city-dwellers allowed homeowners to “rise above a sea of manure.” In Rochester, N. Y., health officials calculated that the city’s annual horse waste would, if collected on a single acre, make a 175-foot-tall tower.

“The world had seemingly reached the point where its largest cities could not survive without the horse but couldn’t survive with it, either,” write Levitt and Dubner. A main solution, as they portray it, came in the form of cars, which, compared to horses, were a godsend, their adoption inevitable. “The automobile, cheaper to own and operate than a horse-drawn vehicle was proclaimed an ‘environmental savior.’ Cities around the world were able to take a deep breath—without holding their noses at last—and resume their march of progress.” To Levitt and Dubner, this historical turnabout teaches that technological innovation solves problems, and if it creates new problems, innovation will solve those, too.

It’s far too simplistic an interpretation. Cars didn’t replace horses, at least not in the way we usually think, and it was social as much as technological progress that solved the era’s pollution problems. As we confront our current car troubles—particulate and greenhouse gas pollutions, accidents and deaths, wasteful swaths of the landscape dedicated to automobiles—these are lessons we’d do well to recall.

More here.

Sunday, November 14, 2021

Discovering the Oldest Figural Paintings on Earth

Morgan Meis in The New Yorker:

Gazing with recognition at this pig, Burhan also noticed the painted silhouettes of two human hands toward its rear. The over-all look of the art work suggested to Burhan that it was very old—but how old?

Gazing with recognition at this pig, Burhan also noticed the painted silhouettes of two human hands toward its rear. The over-all look of the art work suggested to Burhan that it was very old—but how old?

Thus began a long process of trying to give the cave art a proper date. Experts were brought in from Griffith. Maxime Aubert, an archeologist and geochemist, decided to use a method called uranium-series dating. He removed some of the calcite on the surface of the painting, which archeologists sometimes call “cave popcorn,” and then analyzed it. Anything under the calcite layer had to be at least as old as what was on the surface. A number of problems arose with the machine that actually did the dating—the Nu Plasma Multi Collector Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer. Like “a Formula One race car,” Aubert said, it requires a team of highly trained engineers just to keep it going. Still, months later, a date was handed down: the painting of the warty pig was at least 45,500 years old. This makes it the oldest known example of figurative cave art in the world.

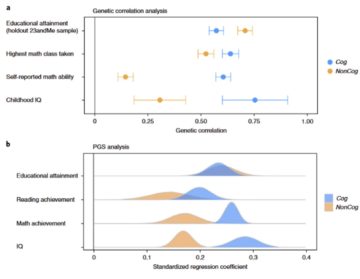

Non-Cognitive Skills For Educational Attainment Suggest Benefits Of Mental Illness Genes

Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

Educational attainment is closely correlated with intelligence, but not perfectly correlated. How far you go in school depends not just on your IQ, but on other skills: how hard-working and motivated you are, how well you can cope with adversity – and arguably also less desirable qualities, like whether you so desperately seek societal approval that you’re willing to throw away your entire twenties on a PhD with no job prospects at the end of it. “Genes for educational attainment” will be a combination of genes for intelligence, and genes for this other stuff.

Educational attainment is closely correlated with intelligence, but not perfectly correlated. How far you go in school depends not just on your IQ, but on other skills: how hard-working and motivated you are, how well you can cope with adversity – and arguably also less desirable qualities, like whether you so desperately seek societal approval that you’re willing to throw away your entire twenties on a PhD with no job prospects at the end of it. “Genes for educational attainment” will be a combination of genes for intelligence, and genes for this other stuff.

At some point, some geneticists just did the hard thing and found some actual genes for actual intelligence, separate from educational attainment. And if you have both the educational attainment genes and the intelligence genes, you can subtract the one from the other to find the non-intelligence-related genes that affect educational attainment in other ways.

More here.

Hollywood Orientalism is not about the Arab world

Hamid Dabashi at Al Jazeera:

“Arabs” are not real people in these works of fiction. Arrakis in Dune are not Iraqis in their homeland. They are figurative, metaphoric and metonymic. They are a mere synecdoche for a literary historiography of American Orientalism. They are tropes – mockups that are there for the white narrator to tell his triumphant story.

“Arabs” are not real people in these works of fiction. Arrakis in Dune are not Iraqis in their homeland. They are figurative, metaphoric and metonymic. They are a mere synecdoche for a literary historiography of American Orientalism. They are tropes – mockups that are there for the white narrator to tell his triumphant story.

The world at large will fall into a trap if we start arguing with these fictive white interlocutors, and telling them we are really not what they think we are. It is not just a losing battle. It is a wrong battle. This is not where the real battle-line is.

You do not fight Hollywood with critical argument. You fight Hollywood with Akira Kurosawa, Satyajit Ray, Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Moufida Tlatli, Ousmane Sembène, Yasujirō Ozu, Guillermo del Toro, Mai Masri, ad gloriam. You do not battle misrepresentation. You signal, celebrate, and polish representations that are works of art.

Aryeh Cohen-Wade & Justin E. H. Smith: How Social Media Swallowed Real Life

Things We Do Not Tell the People We Love by Huma Qureshi – tales of everyday tragedy

Holly Williams in The Guardian:

Huma Qureshi has the perfect title for her short story collection. Things We Do Not Tell the People We Love strikingly encapsulates a major theme of the book: the inability to communicate honestly with the most important people in your life. Qureshi’s stories keenly identify the everyday tragedies of feeling profoundly unknown or unheard, of holding secrets and misunderstandings.

Huma Qureshi has the perfect title for her short story collection. Things We Do Not Tell the People We Love strikingly encapsulates a major theme of the book: the inability to communicate honestly with the most important people in your life. Qureshi’s stories keenly identify the everyday tragedies of feeling profoundly unknown or unheard, of holding secrets and misunderstandings.

Formerly a writer for the Observer and the Guardian, Qureshi published a memoir, How We Met, earlier this year about dating men her parents considered marriage material, before falling in love with a white British man. Her own story could slot neatly into this, her first fiction anthology. Qureshi’s stories feature a cast of – mostly – youngish women of Pakistani heritage, often struggling with overbearing, judgmental and oppressive mothers, blindly insensitive male partners, or both. These tales vividly capture the experience of feeling constrained by family expectations, but also of not quite fitting the norms of British culture either.

The terrain can get repetitive; this dilemma is usually felt by women who’ve left behind immigrant communities for a white, middle-class London milieu; there are many writers and journalists. Pressure points recur, too: in several stressful holidays, tolerable relationships become intolerable. And occasionally, the responses to monstrous mothers tip into melodrama; although it won the Harper’s Bazaar 2020 short story prize, I didn’t quite buy the murderous intent in The Jam Maker.

More here.

No One Cares!

Arthur C. Brooks in The Atlantic:

A friend of mine once shared what I considered a bit of unadulterated wisdom: “If I wouldn’t invite someone into my house, I shouldn’t let them into my head.” But that’s easier said than done. Social media has opened up our heads so that just about any trespasser can wander in. If you tweet whatever crosses your mind about a celebrity, it could quite possibly reach the phone in her hand as she sits on her couch in her house.

A friend of mine once shared what I considered a bit of unadulterated wisdom: “If I wouldn’t invite someone into my house, I shouldn’t let them into my head.” But that’s easier said than done. Social media has opened up our heads so that just about any trespasser can wander in. If you tweet whatever crosses your mind about a celebrity, it could quite possibly reach the phone in her hand as she sits on her couch in her house.

The real problem isn’t technology—it’s human nature. We are wired to care about what others think of us. As the Roman Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius observed almost 2,000 years ago, “We all love ourselves more than other people, but care more about their opinion than our own,” whether they are friends, strangers, or enemies.

This tendency may be natural, but it can drive us around the bend if we let it. If we were perfectly logical beings, we would understand that our fears about what other people think are overblown and rarely worth fretting over. But many of us have been indulging this bad habit for as long as we can remember, so we need to take deliberate steps to change our minds.

More here.

Graeme Edge (1941 – 2021) drummer

Don Maddox (1923 – 2021) musician

Dean Stockwell (1936 – 2021) actor

Sunday Poem

Taos Mountain

“Though the mountains fall into the sea”

describes the faith of some, but the mountains do not move

whatever we say, whatever saints and shamans do.

It is their indifference to us that makes them sacred.

On the edge of this flat town, beyond the pueblo,

the black mountain rises, a reference point

to every human moment, utterly silent.

No one climbs this mountain, there are no trails,

because the place is holy: it does not exist to serve us,

it is not meant to please us, it simply is,

and in this way it is a god.

Mountains do not move, and that is their mountainness.

Geologists can say they have moved over time,

but not in human time. This mountain outside my window

has always been there: when the pueblo was built,

when the Spanish came and were driven away,

when the missionaries returned, then Americans and Apache.

The mountain abides. That is its power

in imagination and worship. Were it to respond

to our prayers and dances it would cease to be itself.

Its silence is what we listen to, and the reason

it is a source of strength. I will not pretend

it whispers secrets to me or that I have pleased it.

The mountain is black even in sunlight or capped with snow.

It may have its back turned to the human

like an inscrutable mother in a shawl.

There are no signs given us to read

and any language to describe it is our own.

The fact of the mountain is our bare and only creed.

by Stephan Hollaway

from The Ecotheo Review

Saturday, November 13, 2021

The Zemmour Effect

Adam Shatz in the LRB’s blog:

Adam Shatz in the LRB’s blog:

‘The American writer in the middle of the 20th century has his hands full in trying to understand, describe, and then make credible much of the American reality,’ Philip Roth wrote in Commentary in 1961. ‘It stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meagre imagination. The actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures almost daily that are the envy of any novelist.’

When Donald Trump was elected president, many people were struck by the eery prescience of Roth’s 2004 novel The Plot Against America, an alternative history in which the right-wing isolationist Charles Lindbergh defeats Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election, imposing a reign of terror. But the Roth of 1961 had it right. Trump provided a humbling reminder that fiction is no match for what Roth called ‘the American berserk’.

America is hardly alone. The most hysterical – and also the most articulate, and therefore dangerous – manifestation of what might be called the French berserk is the journalist and potential presidential contender Éric Zemmour. His emergence has thrown into relief the ‘meagre imagination’ even of Michel Houellebecq, whose 2015 novel Soumission told the story of a Muslim businessman of Tunisian origin who becomes France’s president and imposes sharia. The reality is no less wild: the rise of a North African Jewish intellectual who calls for the rehabilitation of Pétain and Vichy, while depicting immigrants and Islam as mortal threats to the Republic.

More here.

Growth Towns

Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World:

Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World:

The ongoing crisis for Chinese property developer Evergrande has made the giant company the focal point of global concern. Creditors, investors, contractors, customers, and employees of Evergrande within and outside China have watched anxiously to see whether the Chinese government would decide that Evergrande was too big to fail. If Evergrande were to collapse, the repercussions for both the financial system and construction supply chains are impossible to predict. Reportedly, the central government in Beijing has issued a warning to local governments to brace for the possible social and political fallout.

Even if Evergrande were salvaged through government intervention, the Chinese state would continue to face new dilemmas. Evergrande is just one of many troubled property development firms that face potential default. As housing prices in China fall, the crisis has already spread to other property developers, such as Kaisa. The US Federal Reserve explicitly warned that China’s housing crisis could spill over to the US and global economy.

The crisis of Evergrande and China’s large property sector is a manifestation of the crisis of China’s growth model. The limits of that model can be seen in ghost towns across the country; China’s empty apartments are estimated to be able to house the entire population of France, Germany, Italy, the UK, or Canada. How could such development sustain high-speed growth for so long, and why has it failed now? To understand the ongoing crisis, we need to understand how property—and fixed investment more broadly—is connected to other moving parts of the Chinese and global economies.

More here.