Richard Overy in TLS:

The nature of the dictatorship clearly mattered because on their own it is unlikely that the military and politicians in either country would have plunged into total war after the bruising experience of 1914–18. Hitler and Mussolini were both obsessed with the idea of living space for peoples whose culture and racial value deserved it; since “space” was actually already occupied by the 1930s, only war would secure more of it. On this crude rationale, both dictators succeeded in persuading or cajoling the broader military and political leadership to follow. In both countries, imperial visions and national resentments already existed. Ullrich makes the obvious but important point that Hitler was not an alien presence, somehow “outside Germany”, but sufficiently linked to a longer German history for his ambitions to be understood, even accepted. Much the same was true for Mussolini, whose imperial appetite was not an aberration, but a product of a long history of Italy trying to vie with the established imperialism of Britain and France.

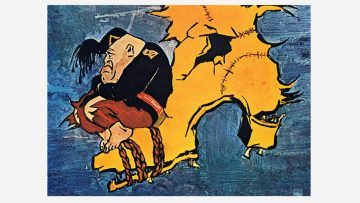

Nevertheless, the dictators were the driving force. Gooch’s Mussolini is the dangerous adventurer, who dreamt of war far beyond Italy’s modest capability. The detailed military history shows the long arc of strategic ineptitude. The invasion of Ethiopia and involvement in the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s were costly and limited conflicts, whose outcome flattered Italian forces. In war against a major power, these limitations were shown up. Gooch does not follow the line that Italians are hopeless soldiers, but he does show that poor staff work, a fatal gap between the officer corps and the rank and file, profound resource constraints, and a dangerous lack of collaboration between the armed services all contributed to undermining what Italian forces, better led and more fully armed, might have achieved. The war against Greece was a classic example. Mussolini quite underestimated the valour and determination of the Greek armed forces, while invading across difficult terrain in late October, when no sensible commander would think of starting a major operation, made a difficult task virtually impossible. Italian forces were confused about the invasion and poorly led. Without German intervention, the Greeks, with British help, might have won, though Gooch does not explicitly say so. The war in the desert against British Commonwealth forces, whose own commanders showed almost as poor a grasp of operational realities, would have been quickly over without German help. By the time of the battles of El Alamein (1942) there were some improvements, but Gooch shows that within days the larger Italian component (too often left out of the standard Western accounts) had run out of ammunition, food and water and could no longer fight. Nothing perhaps captures the cloud-cuckoo land inhabited by Mussolini better than his response to defeat in North Africa, cited by Gooch: “In the summer we’ll retake the initiative with a great offensive push towards Algeria [and] Morocco and to reconquer Libya”. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Italian generals a few weeks later began to plot the arrest and overthrow of their wayward commander.

More here.