A Modified Villanelle for my Childhood

…… —with some help from Ahmad

I wanna write lyrical, but all I got is magical.

My book needs a poem talkin bout I remember when

Something more autobiographical

Mi familia wanted to assimilate, nothing radical,

Each month was a struggle to pay our rent

With food stamps, so dust collects on the magical.

Each month it got a little less civil

Isolation is a learned defense

When all you wanna do is write lyrical.

None of us escaped being a criminal

Of the state, institutionalized when

They found out all we had was magical.

White room is white room, it’s all statistical—

Our calendars were divided by Sundays spent

In visiting hours. Cold metal chairs deny the lyrical.

I keep my genes in the sharp light of the celestial.

My history writes itself in sheets across my veins.

My parents believed in prayer, I believed in magical

Well, at least I believed in curses, biblical

Or not, I believed in sharp fists,

Beat myself into lyrical.

But we were each born into this, anger so cosmical

Or so I thought, I wore ten chokers and a chain

Couldn’t see any significance, anger is magical.

Fists to scissors to drugs to pills to fists again

Did you know a poem can be both mythical and archeological?

I ignore the cataphysical, and I anoint my own clavicle.

by Suzi F. Garcia

from the Academy of American Poets

At many points over the past decades I have managed to convince even myself that I am cured. In fact I had managed to do this for almost twenty years, until the beginning of the pandemic, when the repressed returned with a vengeance. I do not believe that I “came down with depression” at that moment, and I especially hate the French habit of speaking of “une dépression”, as if the condition were as individuable and as temporally bounded as a cold. Just as inadequate is the oft-repeated Churchillian metaphor of depression as “the black dog”. If only it were a black dog, I could just kick the fucking thing away. I do not “have” “a” depression, let alone a depression hounding me in the form of an external malevolent agent. Rather, I am depressed, and certain circumstances make this fact less easy to ignore than others. In the event, the circumstances surely had something to do with the first lockdown of March, 2020, which we endured in Brooklyn, right next to the hospital in Fort Greene where they stored the corpses outside in refrigerated trucks. My own experience of covid was mild in its symptoms, but I emerged from lockdown transformed, physically and psychologically.

At many points over the past decades I have managed to convince even myself that I am cured. In fact I had managed to do this for almost twenty years, until the beginning of the pandemic, when the repressed returned with a vengeance. I do not believe that I “came down with depression” at that moment, and I especially hate the French habit of speaking of “une dépression”, as if the condition were as individuable and as temporally bounded as a cold. Just as inadequate is the oft-repeated Churchillian metaphor of depression as “the black dog”. If only it were a black dog, I could just kick the fucking thing away. I do not “have” “a” depression, let alone a depression hounding me in the form of an external malevolent agent. Rather, I am depressed, and certain circumstances make this fact less easy to ignore than others. In the event, the circumstances surely had something to do with the first lockdown of March, 2020, which we endured in Brooklyn, right next to the hospital in Fort Greene where they stored the corpses outside in refrigerated trucks. My own experience of covid was mild in its symptoms, but I emerged from lockdown transformed, physically and psychologically. Today, the most powerful artificial intelligence systems employ a type of machine learning called deep learning. Their algorithms learn by processing massive amounts of data through hidden layers of interconnected nodes, referred to as deep neural networks. As their name suggests, deep neural networks were inspired by the real neural networks in the brain, with the nodes modeled after real neurons—or, at least, after what neuroscientists knew about neurons back in the 1950s, when an influential neuron model called the perceptron was born. Since then, our understanding of the computational complexity of single neurons has dramatically expanded, so biological neurons are known to be more complex than artificial ones. But by how much?

Today, the most powerful artificial intelligence systems employ a type of machine learning called deep learning. Their algorithms learn by processing massive amounts of data through hidden layers of interconnected nodes, referred to as deep neural networks. As their name suggests, deep neural networks were inspired by the real neural networks in the brain, with the nodes modeled after real neurons—or, at least, after what neuroscientists knew about neurons back in the 1950s, when an influential neuron model called the perceptron was born. Since then, our understanding of the computational complexity of single neurons has dramatically expanded, so biological neurons are known to be more complex than artificial ones. But by how much? One of Mao Zedong’s best-known sayings is: “There is great disorder under heaven; the situation is excellent.” It is easy to understand what Mao meant here: when the existing social order is disintegrating, the ensuing chaos offers revolutionary forces a great chance to act decisively and assume political power. Today, there certainly is great disorder under heaven: the Covid-19 pandemic, global warming, signs of a new Cold War, and the eruption of popular protests and social antagonisms are just a few of the crises that beset us. But does this chaos still make the situation excellent, or is the danger of self-destruction too high? The difference between the situation that Mao had in mind and our own situation can be best rendered by a tiny terminological distinction. Mao speaks about disorder UNDER heaven, wherein “heaven,” or the big Other in whatever form—the inexorable logic of historical processes, the laws of social development—still exists and discreetly regulates social chaos. Today, we should talk about HEAVEN ITSELF as being in disorder. What do I mean by this?

One of Mao Zedong’s best-known sayings is: “There is great disorder under heaven; the situation is excellent.” It is easy to understand what Mao meant here: when the existing social order is disintegrating, the ensuing chaos offers revolutionary forces a great chance to act decisively and assume political power. Today, there certainly is great disorder under heaven: the Covid-19 pandemic, global warming, signs of a new Cold War, and the eruption of popular protests and social antagonisms are just a few of the crises that beset us. But does this chaos still make the situation excellent, or is the danger of self-destruction too high? The difference between the situation that Mao had in mind and our own situation can be best rendered by a tiny terminological distinction. Mao speaks about disorder UNDER heaven, wherein “heaven,” or the big Other in whatever form—the inexorable logic of historical processes, the laws of social development—still exists and discreetly regulates social chaos. Today, we should talk about HEAVEN ITSELF as being in disorder. What do I mean by this? The term “gaslighting” has returned to the popular lexicon over the past decade, when as recently as the turn of the millennium it had fallen into near-complete disuse. It was then that I first heard the word myself, in the context of a Steely Dan song from 2000, “Gaslighting Abbie.” Not only did I have no idea what it meant, I had only the vaguest sense of who Steely Dan were. But I was, at least, in the right place: a university-district high-end stereo shop, the kind of audiophile’s sacred space that has provided countless “Danfans” their first proper experience of the band — that is, of the band’s records, played back on a sound system of high enough fidelity to do justice to the enormously costly, complex, and time-consuming labors of recording and production that went into them. “Gaslighting Abbie” alone required 26 straight eight-hour days in the studio to get right.

The term “gaslighting” has returned to the popular lexicon over the past decade, when as recently as the turn of the millennium it had fallen into near-complete disuse. It was then that I first heard the word myself, in the context of a Steely Dan song from 2000, “Gaslighting Abbie.” Not only did I have no idea what it meant, I had only the vaguest sense of who Steely Dan were. But I was, at least, in the right place: a university-district high-end stereo shop, the kind of audiophile’s sacred space that has provided countless “Danfans” their first proper experience of the band — that is, of the band’s records, played back on a sound system of high enough fidelity to do justice to the enormously costly, complex, and time-consuming labors of recording and production that went into them. “Gaslighting Abbie” alone required 26 straight eight-hour days in the studio to get right. In his essay Sexual Objectification, Timo Jütten explains how sexual objectification teaches men and women to assume roles as superiors and subordinates, roles that disadvantage women and leave them vulnerable to gender-specific harms, such as sexual assault and rape. While I knew this already, it is a small relief to read it in print. Most women instinctively know that their bodies are a hair’s breadth away from violence. The artist Marina Abramović demonstrated this by laying seventy-two objects on a table—a tube of lipstick, a feather, a knife, and a gun—and invited gallery viewers to do whatever they wanted to her for six hours. At first the people were shy, presenting her with the flower, kissing her, draping her in cloth; then as the hours ticked off, one man snipped off her clothes with the scissors so that she was bare, and another sliced her with the knife. Someone else picked up the gun from the table, wrapped her hand around it, and pointed it at her neck. At the end she stood up to leave, bare, and bleeding, and the audience fled.

In his essay Sexual Objectification, Timo Jütten explains how sexual objectification teaches men and women to assume roles as superiors and subordinates, roles that disadvantage women and leave them vulnerable to gender-specific harms, such as sexual assault and rape. While I knew this already, it is a small relief to read it in print. Most women instinctively know that their bodies are a hair’s breadth away from violence. The artist Marina Abramović demonstrated this by laying seventy-two objects on a table—a tube of lipstick, a feather, a knife, and a gun—and invited gallery viewers to do whatever they wanted to her for six hours. At first the people were shy, presenting her with the flower, kissing her, draping her in cloth; then as the hours ticked off, one man snipped off her clothes with the scissors so that she was bare, and another sliced her with the knife. Someone else picked up the gun from the table, wrapped her hand around it, and pointed it at her neck. At the end she stood up to leave, bare, and bleeding, and the audience fled. Readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous prose and poetry might be unaware of how often he wrote about science. As John Tresch explains in “The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science,” in the late 1840s, near the end of his life, Poe had established for himself “a unique position as fiction writer, poet, critic, and expert on scientific matters – crossing paths with and learning from those who were producing the ‘apparent miracles’ of modern science.”

Readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous prose and poetry might be unaware of how often he wrote about science. As John Tresch explains in “The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science,” in the late 1840s, near the end of his life, Poe had established for himself “a unique position as fiction writer, poet, critic, and expert on scientific matters – crossing paths with and learning from those who were producing the ‘apparent miracles’ of modern science.” Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World: Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar: Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook:

Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook: “Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground.

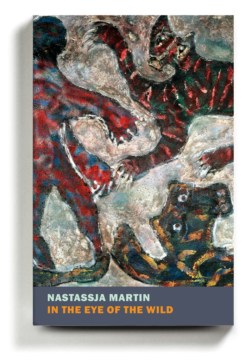

“Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground. W

W Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said.

Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said.