Gerald Early in The Common Reader:

In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.

In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.

More here.

Today the reduction procedure, known as the Laporta algorithm, has become the main tool for generating precise predictions about particle behavior. “It’s ubiquitous,” said

Today the reduction procedure, known as the Laporta algorithm, has become the main tool for generating precise predictions about particle behavior. “It’s ubiquitous,” said  The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) fell far short of what is needed for a safe planet, owing mainly to the same lack of trust that has burdened global climate negotiations for almost three decades. Developing countries regard climate change as a crisis caused largely by the rich countries, which they also view as shirking their historical and ongoing responsibility for the crisis. Worried that they will be left paying the bills, many key developing countries, such as India, don’t much care to negotiate or strategize.

The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) fell far short of what is needed for a safe planet, owing mainly to the same lack of trust that has burdened global climate negotiations for almost three decades. Developing countries regard climate change as a crisis caused largely by the rich countries, which they also view as shirking their historical and ongoing responsibility for the crisis. Worried that they will be left paying the bills, many key developing countries, such as India, don’t much care to negotiate or strategize. My last pandemic Thanksgiving dinner began in a jet black convertible-turned-restaurant booth where I watched as a teenaged pizzamaker took a break from scattering toppings on my 18-inch Supreme pie to take a hit and turn up “Heartbreakin’ Man” by My Morning Jacket. Spinelli’s Pizzeria in Louisville’s Highland neighborhood possesses a kind of curated grime. It’s covered in graffiti-style art (which is unsurprising because its staff is often a rotation of local taggers) and is packed with muscle car and pop culture ephemera, including a

My last pandemic Thanksgiving dinner began in a jet black convertible-turned-restaurant booth where I watched as a teenaged pizzamaker took a break from scattering toppings on my 18-inch Supreme pie to take a hit and turn up “Heartbreakin’ Man” by My Morning Jacket. Spinelli’s Pizzeria in Louisville’s Highland neighborhood possesses a kind of curated grime. It’s covered in graffiti-style art (which is unsurprising because its staff is often a rotation of local taggers) and is packed with muscle car and pop culture ephemera, including a  The

The  A.S. Byatt’s reputation as a master of the long form has been crystallized by Possession, a novel of depth, breadth and heft; the “Frederica Quartet,” a prose tapestry of post-war England; and The Children’s Book, a many-chambered country house of a narrative. Her new collection, Medusa’s Ankles, showcases Byatt’s gifts as a master of the short story. To my mind, she belongs in that select club of writers whose members include Dickens, John Cheever, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Elizabeth Bowen, and who achieve virtuosity in both short- and long-form fiction.

A.S. Byatt’s reputation as a master of the long form has been crystallized by Possession, a novel of depth, breadth and heft; the “Frederica Quartet,” a prose tapestry of post-war England; and The Children’s Book, a many-chambered country house of a narrative. Her new collection, Medusa’s Ankles, showcases Byatt’s gifts as a master of the short story. To my mind, she belongs in that select club of writers whose members include Dickens, John Cheever, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Elizabeth Bowen, and who achieve virtuosity in both short- and long-form fiction. Metaculus predicts

Metaculus predicts Superhero movies offer plenty of drama: big personalities, colorful explosions, the fate of the world hanging on the contest between good and evil. Thrilling as they may be, these movies don’t provide much practical guidance about saving the real world, where our problems demand more grappling with ambiguity than derring-do. Yet you can see the influence of superhero theatrics in public discourse about the culture wars. On Twitter and in podcasts, everything now seems to be an epochal struggle between two factions, the “Wokeists” and the “anti-Wokeists,” whose battles over social justice will doom or save us all.

Superhero movies offer plenty of drama: big personalities, colorful explosions, the fate of the world hanging on the contest between good and evil. Thrilling as they may be, these movies don’t provide much practical guidance about saving the real world, where our problems demand more grappling with ambiguity than derring-do. Yet you can see the influence of superhero theatrics in public discourse about the culture wars. On Twitter and in podcasts, everything now seems to be an epochal struggle between two factions, the “Wokeists” and the “anti-Wokeists,” whose battles over social justice will doom or save us all. Much of this progressive ire is directed at the presence of cars in cities. It resists how cities are shaped to suit the needs and preferences of drivers. But the attitude easily extends to sneering at rural or suburban life, especially when it seems to bleed over into cities. Consider the broad dislike of SUVs.

Much of this progressive ire is directed at the presence of cars in cities. It resists how cities are shaped to suit the needs and preferences of drivers. But the attitude easily extends to sneering at rural or suburban life, especially when it seems to bleed over into cities. Consider the broad dislike of SUVs.  Sylvère’s way of creating accidents or chance was like this: He’d come in to the classroom of about five to ten students, depending on the day, and begin thinking aloud about literature, art, and philosophy—in French or occasionally heavily accented English—in a way that I only understood, at some point during my second or third Sylvère semester, was intended to “disorganize” us, his students, regardless of our level. If we asked him to explain “structuralism,” he might lecture on Saussure and Barthes for a while, but then go off into Nietzsche, the schizophrenic writings of Judge Daniel Paul Schreber, and onto Deleuze, thus making clear the limitations of any rage for ordering things. Sylvère encouraged or provoked everyone to excess. Even the French graduate student who gave a seemingly flawless presentation on the idea of “la grève” in Mallarmé and Rimbaud, and who once accused me of working for the police when I asked him how long he was staying at Columbia—a true disciple if ever there was one—Sylvère blew up his presentation, too.

Sylvère’s way of creating accidents or chance was like this: He’d come in to the classroom of about five to ten students, depending on the day, and begin thinking aloud about literature, art, and philosophy—in French or occasionally heavily accented English—in a way that I only understood, at some point during my second or third Sylvère semester, was intended to “disorganize” us, his students, regardless of our level. If we asked him to explain “structuralism,” he might lecture on Saussure and Barthes for a while, but then go off into Nietzsche, the schizophrenic writings of Judge Daniel Paul Schreber, and onto Deleuze, thus making clear the limitations of any rage for ordering things. Sylvère encouraged or provoked everyone to excess. Even the French graduate student who gave a seemingly flawless presentation on the idea of “la grève” in Mallarmé and Rimbaud, and who once accused me of working for the police when I asked him how long he was staying at Columbia—a true disciple if ever there was one—Sylvère blew up his presentation, too. T

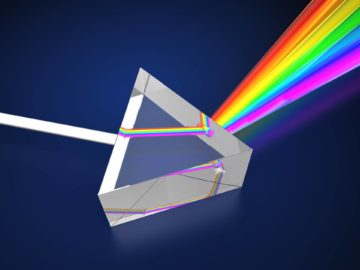

T Scientific terms are often used interchangeably, and scientifically-accepted descriptions are constantly being refined and reinterpreted, which can lead to errors in scientific understanding. While such errors can’t be completely eliminated, they can be reduced by making ourselves aware of them, better understanding the terminology, and using thoughtful and careful scientific methods. This is certainly true when it comes to understanding spectroscopy and spectrometry which, despite being similar, aren’t the same thing. With this in mind, let’s take a deeper look at these terms.

Scientific terms are often used interchangeably, and scientifically-accepted descriptions are constantly being refined and reinterpreted, which can lead to errors in scientific understanding. While such errors can’t be completely eliminated, they can be reduced by making ourselves aware of them, better understanding the terminology, and using thoughtful and careful scientific methods. This is certainly true when it comes to understanding spectroscopy and spectrometry which, despite being similar, aren’t the same thing. With this in mind, let’s take a deeper look at these terms. Imagine a world haunted not just by the dead, but by the specter of death. Drawn ever closer by the already locked-in consequences of our actions and inaction. Its domain extended by endless escalating catastrophe.

Imagine a world haunted not just by the dead, but by the specter of death. Drawn ever closer by the already locked-in consequences of our actions and inaction. Its domain extended by endless escalating catastrophe. Since COVID-19 first pummeled the U.S., Americans have been told to flatten the curve lest hospitals be overwhelmed.

Since COVID-19 first pummeled the U.S., Americans have been told to flatten the curve lest hospitals be overwhelmed.