Kathryn Hughes at The Guardian:

Publishers are getting ready to celebrate the centenary of 1922, the year the world emerged from war and pandemic to become recognisably modern. It was then that James Joyce’s Ulysses and TS Eliot’s The Waste Land were published, the USSR and the BBC were established and Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered. If this last example seems slight by comparison, it is worth remembering that the craze for Egyptian hieroglyphics fed directly into art deco, the visual style that is synonymous with the “roaring 20s” to this day.

Publishers are getting ready to celebrate the centenary of 1922, the year the world emerged from war and pandemic to become recognisably modern. It was then that James Joyce’s Ulysses and TS Eliot’s The Waste Land were published, the USSR and the BBC were established and Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered. If this last example seems slight by comparison, it is worth remembering that the craze for Egyptian hieroglyphics fed directly into art deco, the visual style that is synonymous with the “roaring 20s” to this day.

Nick Rennison has sensibly got in early, bringing out his Scenes from a Turbulent Year while other authors and publishers are still putting the finishing touches to their manuscripts. In this enjoyable slice of popular history, he assembles a month-by-month almanac, including all the most notable moments from science, politics, art and culture.

more here.

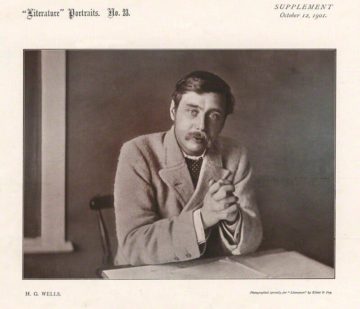

“There was a period when he was turning out 7,000 words a day,” writes Tomalin. “He kept working at what seems an impossible rate, producing stories so varied one might easily think they came from a team of writers.” Few writers will equal his worldwide impact on letters. With Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback, he invented the genre of science fiction. A crater on the moon’s far side is named after him. Nominated four times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Wells, the futurist, foresaw the coming of aircraft, tanks, the sexual revolution, the atomic bomb, and created the classic templates for every story that has been written about alien invasion (his inspiration for “The War of the Worlds,” says Tomalin, was “Tasmania, and the disaster the arrival of the Europeans had been for its people, who were annihilated”) and time travel (he was the first to imagine such travel made possible by a machine).

“There was a period when he was turning out 7,000 words a day,” writes Tomalin. “He kept working at what seems an impossible rate, producing stories so varied one might easily think they came from a team of writers.” Few writers will equal his worldwide impact on letters. With Jules Verne and the publisher Hugo Gernsback, he invented the genre of science fiction. A crater on the moon’s far side is named after him. Nominated four times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Wells, the futurist, foresaw the coming of aircraft, tanks, the sexual revolution, the atomic bomb, and created the classic templates for every story that has been written about alien invasion (his inspiration for “The War of the Worlds,” says Tomalin, was “Tasmania, and the disaster the arrival of the Europeans had been for its people, who were annihilated”) and time travel (he was the first to imagine such travel made possible by a machine). Willem deVries in Aeon:

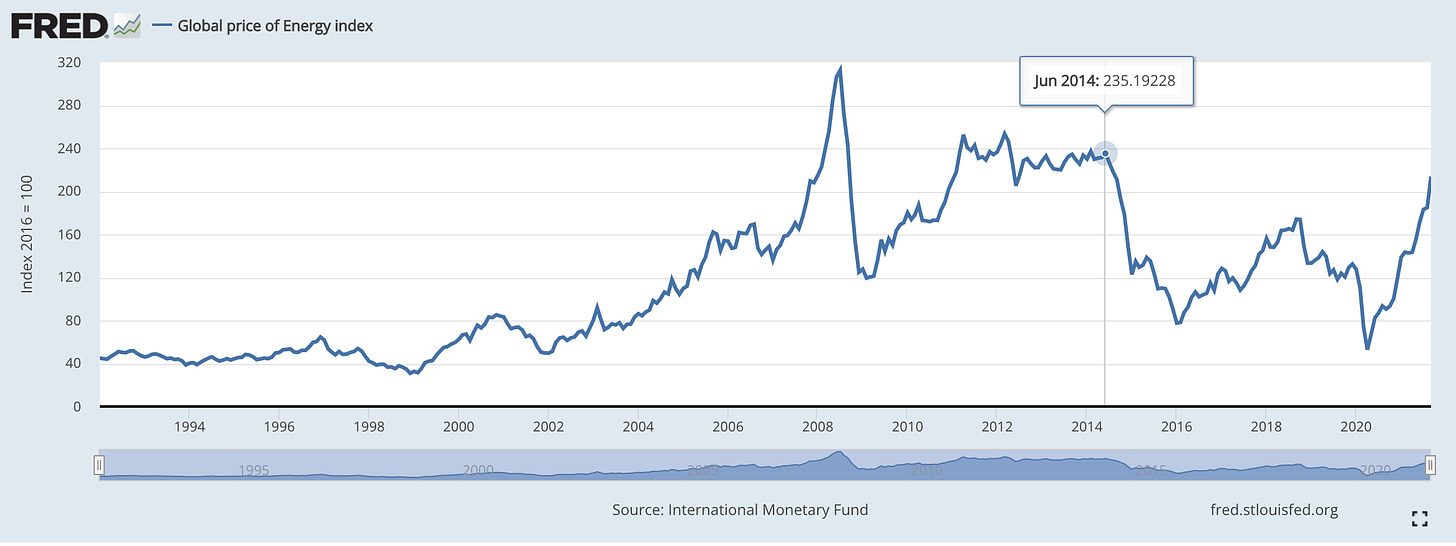

Willem deVries in Aeon: Cedric Durand and Adam Tooze debate if and how the current shortfall in energy supply is directly connected to climate policy. First,

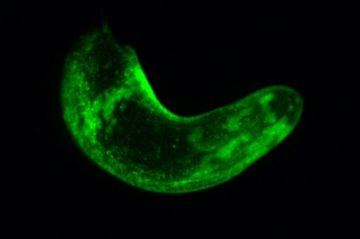

Cedric Durand and Adam Tooze debate if and how the current shortfall in energy supply is directly connected to climate policy. First,  IN 1961, OSAMU SHIMOMURA AND

IN 1961, OSAMU SHIMOMURA AND On Christmas Day in 1839, 17-year-old

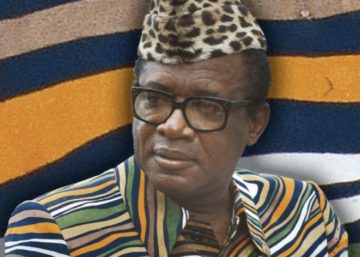

On Christmas Day in 1839, 17-year-old  The pursuit of authenticity in fashion has taken more than a few interesting turns in the modern world. Consider its role in the political project of President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, who during the early 1970s imposed a series of cultural reforms known as the retour à l’authenticité (return to authenticity) designed to rid the nation of European influences. Cities named after Europeans and colonial officials were given African names: Leopoldville became Kinshasa; Stanleyville, named after the Welsh explorer who established European rule, became Kisangani. Mobutu’s government encouraged citizens to change their Christian names and threatened any parent giving a child a Western name with five years’ imprisonment.

The pursuit of authenticity in fashion has taken more than a few interesting turns in the modern world. Consider its role in the political project of President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, who during the early 1970s imposed a series of cultural reforms known as the retour à l’authenticité (return to authenticity) designed to rid the nation of European influences. Cities named after Europeans and colonial officials were given African names: Leopoldville became Kinshasa; Stanleyville, named after the Welsh explorer who established European rule, became Kisangani. Mobutu’s government encouraged citizens to change their Christian names and threatened any parent giving a child a Western name with five years’ imprisonment. Any attempt to describe the universe as a totality inevitably involves self-reference. This isn’t something that one often confronts in physics. Most day-to-day physics is modelling other systems: cells, gases, planets. We maintain a separation of subject and object, or of investigator and system being investigated. And even though cosmology is explicitly devoted to the study of the universe as a whole, it is customary in cosmology to maintain the imaginative fiction that we – the people modelling the universe – are looking at it from the outside. We adopt, that is to say, the God’s Eye View.

Any attempt to describe the universe as a totality inevitably involves self-reference. This isn’t something that one often confronts in physics. Most day-to-day physics is modelling other systems: cells, gases, planets. We maintain a separation of subject and object, or of investigator and system being investigated. And even though cosmology is explicitly devoted to the study of the universe as a whole, it is customary in cosmology to maintain the imaginative fiction that we – the people modelling the universe – are looking at it from the outside. We adopt, that is to say, the God’s Eye View. What is worrisome about the lab-leak controversy therefore is not only that our public discussions and political decisions about Covid-19 may have been hampered by the experts’ mischaracterization of scientific knowledge. The long-term danger is that the experts themselves have helped to undermine public trust in scientific expertise and the institutions that depend on it, at a moment when such knowledge is more deeply intertwined with our social and political life than ever before.

What is worrisome about the lab-leak controversy therefore is not only that our public discussions and political decisions about Covid-19 may have been hampered by the experts’ mischaracterization of scientific knowledge. The long-term danger is that the experts themselves have helped to undermine public trust in scientific expertise and the institutions that depend on it, at a moment when such knowledge is more deeply intertwined with our social and political life than ever before. Petite maman seems an unlikely project for Sciamma, who has tended to be very much a realist director. Yet the film is absolutely of a piece with her previous depictions of female experience at different ages – whether depicting the shifting identities and burgeoning desires of teenagers in her debut Water Lilies (2007) and her breakthrough film Girlhood (2014) or investigating nonconformist gender identity at an earlier age, in her altogether ahead-of-its-time Tomboy (2011). It was 2019’s ambitious Portrait of a Lady on Fire – a lesbian romance set in the 18th century – that confirmed her international auteur renown and that also made her a prominent figurehead in contemporary women’s cinema (even a name emblazoned on T-shirts). But Portrait also marked a shift from conventional realism into a stripped back, imaginative realm of poetic filmmaking, an investigation she pursues further in the concise (72-minute), sparely crafted Petite maman.

Petite maman seems an unlikely project for Sciamma, who has tended to be very much a realist director. Yet the film is absolutely of a piece with her previous depictions of female experience at different ages – whether depicting the shifting identities and burgeoning desires of teenagers in her debut Water Lilies (2007) and her breakthrough film Girlhood (2014) or investigating nonconformist gender identity at an earlier age, in her altogether ahead-of-its-time Tomboy (2011). It was 2019’s ambitious Portrait of a Lady on Fire – a lesbian romance set in the 18th century – that confirmed her international auteur renown and that also made her a prominent figurehead in contemporary women’s cinema (even a name emblazoned on T-shirts). But Portrait also marked a shift from conventional realism into a stripped back, imaginative realm of poetic filmmaking, an investigation she pursues further in the concise (72-minute), sparely crafted Petite maman. Although there is something oblique about these conceits, Calle is associated, above all, with acts of bald exposure. Her celebrity, which now extends far beyond France, has long been attached to charges of voyeurisme and exhibitionnisme (which have sometimes resulted in legal trouble). Yet, as “The Hotel” vividly shows, what Calle is really looking for is more enigmatic and compelling than other people’s dirty laundry. Rather than erase the residue of human presence, as a “real” maid is expected to, Calle does the opposite, preserving every stain and scrap as a sign or symbol. But of what? This is the question at the heart of Calle’s work, and the answer may hardly be the point; what interests her most is the seduction and projection involved in knowing another person—how fantasy intervenes in every attempt to see and be seen.

Although there is something oblique about these conceits, Calle is associated, above all, with acts of bald exposure. Her celebrity, which now extends far beyond France, has long been attached to charges of voyeurisme and exhibitionnisme (which have sometimes resulted in legal trouble). Yet, as “The Hotel” vividly shows, what Calle is really looking for is more enigmatic and compelling than other people’s dirty laundry. Rather than erase the residue of human presence, as a “real” maid is expected to, Calle does the opposite, preserving every stain and scrap as a sign or symbol. But of what? This is the question at the heart of Calle’s work, and the answer may hardly be the point; what interests her most is the seduction and projection involved in knowing another person—how fantasy intervenes in every attempt to see and be seen. Though the moon was long considered a barren, inhospitable rocky world, researchers over the past few decades have found that the moon has many of the amenities that humans would need to build a self-sufficient habitat. Indeed, recent discoveries of

Though the moon was long considered a barren, inhospitable rocky world, researchers over the past few decades have found that the moon has many of the amenities that humans would need to build a self-sufficient habitat. Indeed, recent discoveries of  When people think of ways to help the world’s poor, a few obvious ideas come to mind:

When people think of ways to help the world’s poor, a few obvious ideas come to mind:  We will meet climate change with real change, and defeat the fossil-fuel industry in the next nine years.

We will meet climate change with real change, and defeat the fossil-fuel industry in the next nine years. In dozens of laboratory freezers at Columbia University in New York City, 60,000 cancer specimens await testing that oncologist Azra Raza, M.D., anticipates will find “cancer’s first cell” — the earliest mutated cell that will eventually multiply to become a cancer — and lead to treatments that knock the disease out before it grows. The blood and bone marrow samples come from nearly every one of her patients of 35 years, provided as they moved through cancer treatment.

In dozens of laboratory freezers at Columbia University in New York City, 60,000 cancer specimens await testing that oncologist Azra Raza, M.D., anticipates will find “cancer’s first cell” — the earliest mutated cell that will eventually multiply to become a cancer — and lead to treatments that knock the disease out before it grows. The blood and bone marrow samples come from nearly every one of her patients of 35 years, provided as they moved through cancer treatment.